Fun and Games

PROFESSOR HIROSHI I S H I I of the MIT Media Laboratory runs back and forth, eager to show me all his exhibits. "Pick up a bottle," he says, standing in front of a colorfully lit stand of glass bottles. I do so and am rewarded by a playful tune. I pick up a second bottle and another instrument joins in, playing in harmony with the first. Pick up the third bottle, and the instrumental trio is complete. Put down one of the bottles and the instrument associated with it stops. I'm intrigued, but Hiroshi is anxious for me to experience more. "Here, look at this," Hiroshi is calling from the other side of the room, "try this." What is going on? I don't know, but it certainly is fun. I could spend the whole day there.

But Hiroshi has more delights to show. Imagine trying to play table tennis on a school of fish, as in figure 4.1. There they are, swimming about the table, their images delivered by a projector located in the ceiling above the table. Each time the ball hits the table surface, the ripples spread out and the fish scatter. But the fish can't get away-it's a small table, and no matter where the fish go, the ball soon scatters

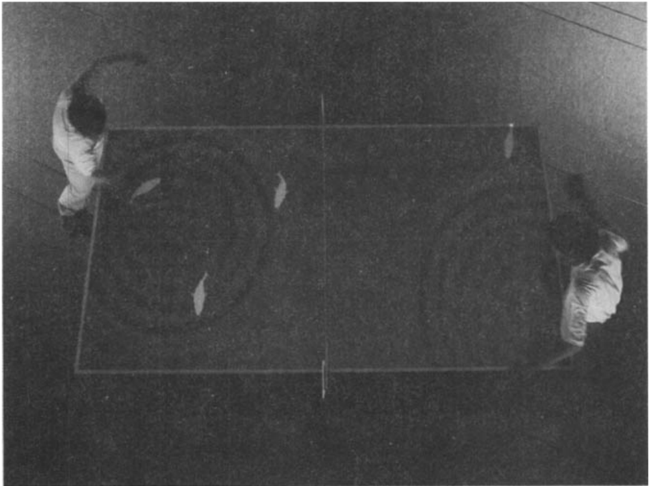

FIGURE 4.1

Table tennis on top of a school of fish.

"Ping Pong Plus." Images of water and a school of fish are projected onto the surface of the ping pong table. Each time the ball hits the table, the computer senses its position, causing the images of ripples to spread out from the ball and the fish to scatter.

(Courtesy of Hiroshi Ishii of the MIT Media Laboratory.)

them again. Is this a good way to play table tennis? No, but that's not what it's about: it's about fun, delight, the pleasure of the experience.

Fun and pleasure, alas, are not topics often covered by science. Science can be too serious, and even when it attempts to examine the issues surrounding fun and pleasure, its very seriousness becomes a distraction. Yes, there are conferences on the scientific basis of humor, of fun ("funology" is the name given to this particular endeavor), but this is a difficult topic and progress is slow. Fun is still an art form, best left to the creative minds of writers, directors, and other artists. But the lack of scientific understanding should not get in the way of our enjoyment. Artists often pave the way, exploring

approaches to human interaction that science then struggles to understand. This has long been true in drama, literature, art, and music, and it is these areas that provide lessons for design. Fun and games: a worthwhile pursuit.

Designing Objects for Fun and Pleasure

Why must information be presented in a dull, dreary fashion, such as in a table of numbers? Most of the time we don't need actual numbers, just some indication of whether the trend is up or down, fast or slow, or some rough estimate of the value. So why not display the information in a colorful manner, continually available in the periphery of attention, but in a way that delights rather than distracts? Once again, Professor Ishii suggests the means: Imagine colorful pinwheels spinning above your head, enjoyable to contemplate, but where the rate of spin is meaningful, perhaps coupled to the outside temperature, or maybe volume of traffic on the roads you use for your daily commute, or for any statistic that is useful to watch. Do you need to be reminded to do something at a specific time? Why not have the pinwheels increase their speed as the time approaches, the higher rate of speed being more likely to attract your attention and, simultaneously, to indicate the urgency. Spinning pinwheels? Why not? Why not have information displayed in a pleasant, comfortable way?

Technology should bring more to our lives than the improved performance of tasks: it should add richness and enjoyment. A good way to bring fun and enjoyment to our lives is to trust in the skill of artists. Fortunately, there are many around.

Consider the pleasure of the Japanese lunchbox, which started as a simple work lunch. In the box lunch you can enjoy a wide assortment of foods, wide enough so that even if you do not like some of the entrees, there are other choices. The box is small, yet fully packed, which poses an aesthetic challenge to the chef. In the best of cases

FIGURE 4.2 The cover of Kenji Ekuan's book

The Aesthetics of the Japanese Lunchbox.

The book illustrates how design should incorporate depth, beauty, and utility. Ekuan demonstrates that the lunchbox is a metaphor for much of Japanese design philosophy. It is art meant to be consumed. It follows the philosophy more is better, offering an assortment of foods so that everyone can find something to their taste. It originated as a practical, working person's lunch, so it combines function, practicality, and beauty-as well as an exercise in philosophy.

(Photograph by Takeshi Do/, with permission of Do/, Ekuan and MIT Press.)

(figure 4.2), the result is a work of art: art meant to be consumed. The Japanese industrial designer Kanji Ekuan has suggested that the aesthetics of the Japanese lunchbox is an excellent metaphor for design. This lunchbox, divided into small compartments, each with five or six types of food, packs twenty to twenty-five colors and flavors within its small space. Ekuan describes it this way:

the cook. . . would naturally be disappointed if the result of such an effort were eaten without a glance or a second thought, (so) he or she

works to make lunchbox meals so attractive that guests are actually reluctant to take up their chopsticks and begin eating. But even so, it is only a matter of time before the masterwork is consumed. The guest senses the formal layout even as he proceeds to break up the perfected layout. This is the inherent and paradoxical relationship between the provision and the acceptance of beauty.

The crowded nature of the lunchbox has many virtues. It forces attention to detail in the arrangement and presentation of the food. This essence of design, packing a lot into a small space while maintaining an aesthetic sense, says Ekuan, is the essence of much of Japan's design for high technology, where one goal is "to establish multifunctionality and miniaturization as equal values. Packing numerous functions into something and making it smaller and thinner are contradictory aims, but one had to pursue contradiction to the limit to find a solution."

The trick is to compress multiple functions into limited space in a way that does not compromise the various dimensions of design. Ekuan clearly prizes beauty-aesthetics-first. "A sense of beauty that lauds lightness and simplicity," he continues, "desire that precipitates functionality, comfort, luxury, diversity. Fulfillment of beauty and its concomitant desire will be the aim of design in the future."

Beauty, fun, and pleasure all work together to produce enjoyment, a state of positive affect. Most scientific studies of emotion have focused upon the negative side, upon anxiety, fear, and anger, even though fun, joy, and pleasure are the desired attributes of life. The climate is changing, with articles and books on "positive psychology" and "well-being" becoming popular. Positive emotions trigger many benefits: They facilitate coping with stress. They are essential to people's curiosity and ability to learn. Here is how the psychologists Barbara Fredrickson and Thomas Joiner describe positive emotions:

positive emotions broaden people's thought-action repertoires, encouraging them to discover novel lines of thought or action. Joy, for

instance, creates the urge to play, interest creates the urge to explore, and so on. Play, for instance, builds physical, socioemotional, and intellectual skills, and fuels brain development. Similarly, exploration increases knowledge and psychological complexity.

It doesn't take much to transform otherwise dull data into a bit of fun. Contrast the style of three major internet search companies. Google stretches out its logo to fit the number of results in a playful, jolly way (figure 4.3). Several people have told me how much they look forward to seeing just how long the Gooooogle will get. But Yahoo, Microsoft network (MSN), and many other sites forgo any notion of fun, and instead present the straightforward results in an unimaginative, orderly way. Small point? Yes, but a meaningful one. Google is known as a playful, fun site-as well as a very useful one-and this playful distortion of its logo helps reinforce this brand image: Fun for the user of the site, good reflective design, and good for business.

The academic, research enterprise of design has not done a good job of studying fun and pleasure. Design is usually thought of as a practical skill, a profession rather than a discipline. In my research for this book, I found lots of literature on behavioral design, much discussion of aesthetics, image, and advertising. The book Emotional

Result Page: 1 8 9 10 Next

FIGURE 4.3

Google plays with their name and logo in a creative, inspiring way. Some searches return multiple pages, so Google modifies its logo accordingly: When I performed a search on the phrase "emotion and design" I got 10 pages of results. Google stretched its logo to put 10 "Os" in its name, providing some fun while also being informative and, best of all, non-intrusive. (Courtesy of Google.)

Branding is a treatment of advertising, for example. Academics have concentrated primarily upon the history of design, or the social history or societal implications, or if they are from the cognitive and computer sciences, upon the study of machine interfaces and usability.

In Designing Pleasurable Products, one of the few scientific studies of pleasure and design, the human factors expert and designer Patrick Jordan builds on the work of Lionel Tiger to identify four kinds of pleasure. Here is my interpretation:

Physio-pleasure. Pleasures of the body. Sights, sounds, smells, taste, and touch. Physio-pleasure combines many aspects of the visceral level with some of the behavioral level.

Socio-pieasure. Social pleasure derived from interaction with others. Jordan points out that many products play an important social role, either by design or by accident. All communication technologies-whether telephone, cell phone, email, instant messaging, or even regular mail-play important social roles by design. Sometimes the social pleasure derives serendipitously as a byproduct of usage. Thus, the office coffeemaker and mailroom serve as focal points for impromptu gatherings at the office. Similarly, the kitchen is the focal point for many social interactions in the home. Socio-pleasure, therefore, combines aspects of both behavioral and reflective design.

Psycho-pleasure. This aspect of pleasure deals with people's reactions and psychological state during the use of products. Psycho-pleasure resides at the behavioral level.

Ideo-pleasure. Here lies the reflection on the experience. This is where one appreciates the aesthetics, or the quality, or perhaps the extent to which a product enhances life and respects the environment. As Jordan points out, the value of many products comes from the statement they make. When displayed so that others can see them, they provide ideo-pleasure to the extent that they signify the value judgments of their owner. Ideo-pleasure clearly lies at the reflective level.

Take the Jordan/Tiger classification, mix with equal parts of the three design levels, and you have a fun and pleasurable end result. But fun and pleasure are elusive concepts. Thus, what is considered delightful depends a lot upon the context. The actions of a kitten or human baby may be judged fun and cute, but the very same actions performed by a cat or human adult can be judged irritating or disgusting. Moreover, what is fun at first can outwear its welcome.

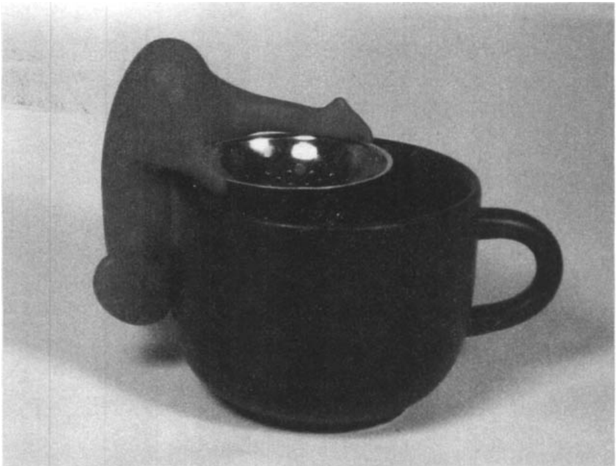

Consider the "Te 6" tea strainer (figure 4.4), designed by Stefano Pirovano for the Italian manufacturing firm Alessi. At first glance it is cute, childish even. As such, it doesn't qualify as fun-not yet. It is a simple animate figure. The day I purchased it, I had lunch with Keiichi Sato, a professor of design at the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design in Chicago. At the lunch table, I proudly displayed my new purchase. Sato's first response was skeptical. "Yes," he said, "it's pleasant and cute, but to what purpose?" But when I placed the strainer on a cup, his eyes lit up, and he laughed (see figure 4.5).

At first sight, the arms and legs of the figure are simply cute, but when it becomes apparent that the cuteness is also functional, then "cute" becomes transformed into "pleasure" and "fun," and this, moreover, is long-lasting. Sato and I spent much of the next hour trying to understand what transforms an impression of shallow cuteness into one of deep, long-lasting pleasure. In the case of the Te 6 strainer, the unexpected transformation is the key. Both of us noted that the essence of the surprise was the separation between the two viewings: first the tea strainer alone, then on the teacup. "If you publish this in your book," Sato warned me, "make sure that you have only the picture of the strainer visible on one page, and make the reader turn the page to see the strainer on a teacup. If you don't do that, the surprise-and the fun-will not be as strong." As you see, I have followed that advice.

What transforms the strainer from "cute" into "fun"? Is it surprise? Cleverness? Certainly both of those traits play a big role.

Does familiarity breed contempt, as the old folk saying would have

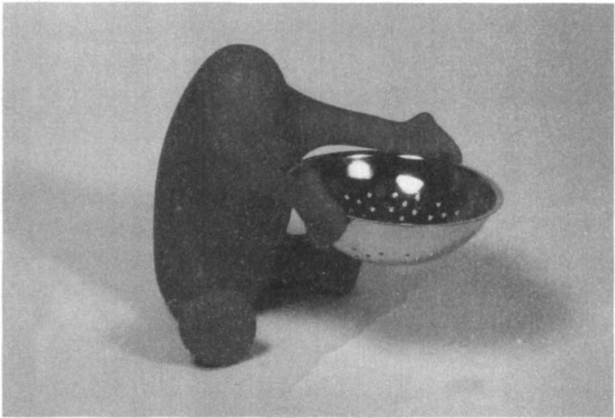

FIGURE 4.4 Stefano Pirovano's Te 6 tea strainer, made by Alessi.

The figure is cute, the color and shapes attractive. Pleasureabie? Yes, slightly. Fun? Not yet.

(Author's collection.)

it? Many things are cute or fun at first, but over time diminish or even become tiresome. In my home the tea strainer is now permanently on display, perched on a teacup nestled among the three teapots on the window shelf of my kitchen. The charm of the tea strainer is that it retains its fun even after considerable use, even though I see it everyday.

Now, the tea strainer is just a trifle, and I do not believe that even Pirovano, its designer, would disagree. But it passes the test of time. This is one of the hallmarks of good design. Great design-like great literature, music, or art-can be appreciated even after continual use, continued presence.

People tend to pay less attention to familiar things, whether it's a possession or even a spouse. On the whole, this adaptive behavior is biologically useful (for objects, events, and situations, not for spouses), because it is usually the novel, unexpected things in life that

FIGURE 4.5 Pirovano's Te 6 tea strainer, ready for use.

Now it's fun.

(Photo by the author.)

require the most attention. The brain naturally adapts to repeated experiences. If I were to show you a series of repeated images and measure your brain responses, the activity would diminish with the repetitions. Your brain would respond again only when something new was presented. Scientists have shown that the biggest responses always come with the least expected event. A simple sentence such as, "He picked up the hammer and nail" gives a tiny response; change the last few words, "He picked up the hammer and ate it," and you'll see a much larger one.

Human adaptation creates a challenge for design, but an opportunity for manufacturers: When people tire of an item, perhaps they will buy a new one. Indeed, the essence of fashion is to make the current trends obsolete and boring, turning them into yesterday's favorites. The attractive appliance of yesterday no longer looks quite as attractive

today. Some of the examples in this book may have already followed this trajectory: the Mini Cooper automobile, so charming and cute to the reviewers at the time of this book's writing, may look dated, oldfashioned, and dull by the time you flip through these pages-so much so that you may wonder how I came to choose it as an example.

The concern for the diminishing impact of familiarity has led some designers to propose hiding beautiful views, lest continual encounter might diminish their emotional impact. In the book A Pattern Language, the architect Christopher Alexander and his colleagues describe 253 different design patterns derived from their observations and analyses. These patterns provide the basis of their guidelines for "a timeless way of building," which structures buildings in ways calculated to enhance the experience of the people living within them. Pattern number 134deals with the problem of overexposure:

Pattern 134: Zen View. If there is a beautiful view, don't spoil it by building huge windows that gape incessantly at it. Instead, put the windows which look onto the view at places of transition-along paths, in hallways, in entry ways, on stairs, between rooms.

If the view window is correctly placed, people will see a glimpse of the distant view as they come up to the window or pass it: but the view is never visible from the places where people stay.

The name "Zen View" comes from "the parable of a Buddhist monk who lived on a mountain with a beautiful view. The monk built a wall that obscured the view from every angle, except for a single fleeting glimpse along the walk up to his hut." In this way, said Alexander and colleagues, "the view of the distant sea is so restrained that it stays alive forever. Who, that has ever seen that view, can ever forget it? Its power will never fade. Even for the man who lives there, coming past that view day after day, it will still be alive."

Most people, however, are not Buddhist monks. Most of us would be unable to resist the temptation to engulf ourselves in such beauty. Whether hiding beauty is appropriate for all of us is up for debate, and

although the fable described as the rationale for the Zen view is interesting, it is opinion, not fact. Given the chance to experience beauty for some period of time, is the total enhancement greater if the beauty is always there to be appreciated, even if it does fade with time? Or is the enhancement greater when it can only be glimpsed now and then? I do not think anyone knows the answer to this query.

I, for one,go straight for immediate enjoyment. I have always built my homes with large windows facing a view (ocean, when I lived in Southern California; pond with geese, ducks, and herons, when I lived in Northern Illinois), so I am not ready to endorse pattern 134, the Zen View, as a universal design principle.

The issue, however, is a real one.How can we maintain excitement, interest, and aesthetic pleasure for a lifetime? I suspect that part of the answer will come from the study of those things that do stand the test of time, such as some music, literature, and art.In all these cases, the works are rich and deep, so that there is something different to beperceived on each experience. Consider classical music. For many it is boring and uninteresting, but for others it can indeed be listened to with enjoyment over a lifetime. I believe that this longevity derives from the richness and complexity of its structure. The music interleaves multiple themes and variations, some simultaneous, some sequential. Human conscious attention is limited by what it can attend to at any moment, which means that consciousness is restricted to a limited subset of the musical relationships. As a result, each new listening focuses upon a different aspect of the music. The music is never boring because it is never the same. I believe a similar analysis will reveal similar richness for all experiences that last: classical music, art, and literature. So, too,with views.

The views I treasure are dynamic. Scenes are continually changing. The vegetation changes with the seasons, the lighting with the time of day. Different animals congregate at different times, and their interactions with one another and with the environment are ever-changing. In California, the waves rolling in from the ocean change continually, reflecting weather patterns from thousands of miles away. The vari-

ous sea animals visible from my windows-brown pelicans, gray whales, the black-suited surfers, and dolphins-varied their activities according to the weather, the time, and the activities of those around them. Why wasn't the Zen view just as rich, just as long lasting?

Maybe the problem lies not in the object being viewed but in the viewer. It's quite possible the Buddhist monk had never learned to look. For once you have learned how to look at, listen to, and analyze what is before you, you realize that the experience is ever changing. The pleasure is forever.

This conclusion has two important implications. First, the object must be rich and complex, one that gives rise to a never-ending interplay among the elements. Second, the viewer must be able to take the time to study, analyze, and consider such rich interplay; otherwise, the scene becomes commonplace. If something is to give lifelong pleasure, two components are required: the skill of the designer in providing a powerful, rich experience, and the skill of the perceiver.

How may a design maintain its effectiveness even after long acquaintance? The secret, say designers Julie Khaslavsky and Nathan Shedroff, is seduction.

The seductive power of the design of certain material and virtual objects can transcend issues of price and performance for buyers and users alike. To many an engineer's dismay, the appearance of a product can sometimes make or break the product's market reaction.What they have in common is the ability to create an emotional bond with their audiences, almost a need for them.

Seduction, Khaslavsky and Shedroff argue, is a process. It gives rise to a rich and compelling experience that lasts over time. Yes, there has to be an initial attraction. But the real trick-and where most products fail-is in maintaining the relationship after that initial burst of enthusiasm. Make something consciously cute where the cuteness is extraneous, irrelevant to the task, and you get frustration, irritation, and resentment. Think how many gadgets or items of furniture you

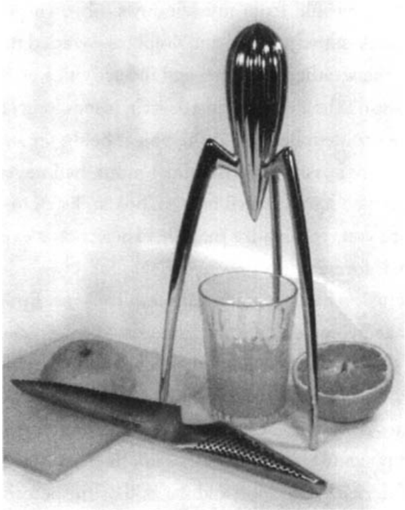

FIGURE 4.6 Two items of seduction.

Philippe Starck's "Juicy Salif" citrus juicer alongside my Global kitchen knife. Rotate the orange half on the ribbed top of the juicer and the juice flows down the sides and drips from the point into the glass. Except this gold-plated version will be damaged by the acidic fluid. As Starck is rumored to have said, "My juicer is not meant to squeeze lemons; it is meant to start conversations." (Author's collection.)

have brought home excitedly and then, after the first use or two, banished to storage. How many survive the passage of time and are still in use, still giving joy? And what is the difference between these two experiences?

Khaslavsky and Shedroff suggest that the three basic steps are enticement relationship, and fulfillment: , make an emotional promise, continually fulfill the promise, and end the experience in a memorable way. They illustrate their argument by examining the citrus juicer designed by Philippe Starck (figure 4.6). The juicer, whose full name

is "Juicy Salif," was designed on a napkin in a pizza parlor in Capraia, an island in Tuscany, Italy. Alberto Alessi, whose company manufacturers them, describes the design this way:

On the napkin, along with some incomprehensible marks (tomato sauce, in all likelihood) there were some sketches. Sketches of squids. They started on the left and, as they worked their way over to the right, they took on the unmistakable shape of what was to become the most celebrated citrus-fruit squeezer of the century that has just come to a close. You can imagine what happened: while eating a dish of squid and squeezing a lemon over it, our man had finally received his inspiration! Juicy Salif was born, and with it some headaches for the champions of "Form follows function."

That juicer was indeed seductive. I saw it and immediately went through the sequence of responses so loved by merchants: "Wow, I want it," I said to myself. Only then did I ask, "What is it? What does it do? How much does it cost?" concluding with "I'll buy it," which I did. That was pure visceral reaction. The juicer is indeed bizarre, but delightful. Why? Fortunately, Khaslavsky and Shedroff have done the analysis for me:

Entices by diverting attention. It is unlike every other kitchen product by nature of its shape, form, and materials.

Delivers surprising novelty. It is not immediatelyidentifiable as a juicer, and its form is unusual enough to be intriguing, even surprising when its purpose first becomes clear.

Goes beyond obvious needs and expectations. To satisfy these criteria-of being surprising and novel-it need only be bright orange or all wood. It goes so far beyond what is expected or required, it becomes something else entirely.

Creates an instinctive response. At first, the shape creates curiosity, then the emotional response of confusion and, perhaps, fear, since it is so sharp and dangerous looking.

Espouses values or connections to personal goals. It transforms the routine act of juicing an orange into a special experience. Its innovative approach, simplicity, and elegance in shape and performance creates an appreciation and the desire to possess not only the object but the values that helped create it, including innovation, originality, elegance, and sophistication. It speaks as much about the person who owns it as it does about its designer.

Promises to fulfill these goals. It promises to make an ordinary action extraordinary. It also promises to raise the status of the owner to a higher level of sophistication for recognizing its qualities.

Leads the casual viewer to discover something deeper about the juicing experience. While the juicer doesn't necessarily teach the user anything new about juice or juicing, it does teach the lesson that even ordinary things in life can be interesting and that design can enhance living. It also teaches to expect wonder where it is unexpected-all positive feelings about the future.

Fulfills these promises. Every time it is used, it reminds the user of its elegance and approach to design. It fulfills these promises through its performance, reconjuring the emotions originally connected with the product. It also serves as a point of surprise and conversation by the associates of its owner-and is another chance to espouse its values and have them validated.

However compelling this analysis of the juicer as an item of seduction, it leaves out one important component: the reflective joy of explanation. The juicer tells a story. Anyone who owns it has to show it off, to explain it, perhaps to demonstrate it. But mind you, the juicer is not really meant to be used to make juice. As Starck is rumored to have said, "My juicer is not meant to squeeze lemons; it is meant to start conversations." Indeed, the version I own, the expensive,numbered, special anniversary edition (gold plated, no less), is explicit: "It is not intended to be used as a juice squeezer," says the numbered card attached to the juicer. "The gold plating could be damaged if it comes into contact with anything acidic."

I bought an expensive juicer, but I am not permitted to use it for making juice! Score zero for behavioral design. But so what? I proudly display the juicer in my entrance hall. Score one hundred for visceral appeal. Score one hundred for reflective appeal. (ButI did use it once for making juice-who could resist?)

Seduction is real. Take the Global kitchen knife of figure 4.6, shown alongside the juicer. Unlike the juicer, which is primarily an object for display, not for use, the knife is beautiful to look at and a joy to use.It is well balanced, it feels good to the hand, and it is sharper than any other knife I have ever owned. Seduction indeed! I look forward to cutting when I cook, for these knives (I own three different types) fulfill all the requirements of seduction put forth by Khaslavsky and Shedroff.

Music and Other Sounds

Music plays a special role in our emotional lives. The responses to rhythm and rhyme, melody and tune are so basic, so constant across all societies and cultures that they must be part of our evolutionary heritage, with many of the responses pre-wired at the visceral level. Rhythm follows the natural beats of the body, with fast rhythms suitable for tapping or marching, slower rhythms for walking, or swaying. Dance, too, is universal. Slow tempos and minor keys are sad. Fast, melodic music that is danceable, with harmonious sounds and relatively constant ranges of pitch and loudness, is happy. Fear is expressed with rapid tempos, dissonance, and abrupt changes in loudness and pitch. The whole brain is involved-perception, action, cognition, and emotion: visceral, behavioral, and reflective. Some aspects of music are common to all people; some vary greatly from culture to culture. Although the neuroscience and psychology of music are widely studied, they are still little understood. We do know that the affective states produced through music are universal, similar across all cultures.

The term "music," of course, covers many activities-composing, performing, listening, singing, dancing. Some activities, such as performing, dancing, and singing, are clearly behavioral. Some, such as composing and listening, are clearly visceral and reflective. The musical experience can range from the one extreme where it is a deep, fully engrossing experience where the mind is fully immersed to the other extreme, where the music is played in the background and not consciously attended to. But even in the latter case, the automatic, visceral processing levels almost definitely register the melodic and rhythmic structure of the music, subtly, subconsciously, changing the affective state of the listener.

Music impacts all three levels of processing. The initial pleasure of the rhythm, tunes, and sounds is visceral, the enjoyment of playing and mastering the parts behavioral, and the pleasure of analyzing the intertwined, repeated, inverted, transformed melodic lines reflective. To the listener, the behavioral side is vicarious. The reflective appeal can come several ways. At one extreme, there is the deep appreciation of the structure of the piece, perhaps of the reference it makes to other pieces of music. This is the level of music appreciation exercised by the critic, the connoisseur, or the scholar. At the other extreme the musical structure and lyrics might be designed to delight, surprise, or shock.

Finally, music has an important behavioral component, either because the person is actively engaged in playing the music or equally actively singing or dancing. But someone who is just listening can also be behaviorally engaged by humming, tapping, or mentally following-and predicting-the piece. Some researchers believe that music is as much a motor activity as a perceptual one, even when simply listening. Moreover, the behavioral level could be involved vicariously, much as it is for the reader of a book or the viewer of a film (a topic I discuss later in this chapter).

Rhythm is built into human biology. There are numerous rhythmic patterns in the body, but the ones of particular interest are those that are relevant to the tempos of music: that is, from a few events per sec-

ond to a few seconds per event. This is the range of body functions such as the beating of the heart and breathing. Perhaps more important, it is also the range of the natural frequencies of body movement, whether walking, throwing, or talking. It is easy to tap the limbs within this range of rates, hard to do it faster or slower. Much as the tempo of a clock is determined by the length of its pendulum, the body can adjust its natural tempo by tensing or relaxing muscles to adjust the effective length of the moving limbs, matching their natural rhythmic frequency to that of the music. It is therefore no accident that in playing music, the entire body keeps the rhythm.

All cultures have evolved musical scales, and although they differ, they all follow similar frameworks. The properties of octaves and of consonant and dissonant chords derive in part from physics, in part from the mechanical properties of the inner ear. Expectations play a central role in creating affective states, as a musical sequence satisfies or violates the expectations built up by its rhythm and tonal sequence. Minor keys have different emotional impact than major keys, universally signifying sadness or melancholy. The combination of key structure, choice of chords, rhythm, and tune, and the continual buildup of tension and instability create powerful affective influences upon us. Sometimes these influences are subconscious, as when music plays in the background during a film, but deliberately scored to invoke specific affective states. Sometimes these are conscious and deliberate, as when we devote our full conscious attention to the music, letting ourselves be carried vicariously by the impact, behaviorally by the rhythm, and reflectively as the mind builds upon the affective state to create true emotions.

We use music to fill the void when pursuing otherwise mindless activities, while stuck on a long, tiring trip, walking a long distance, exercising, or simply killing time. Once upon a time, music was not portable. Before the invention of the phonograph, music could be heard only when there were musicians. Today we carry our music players with us and we can listen twenty-four hours a day if we wish. Airlines realize music is so essential that they provide a choice of

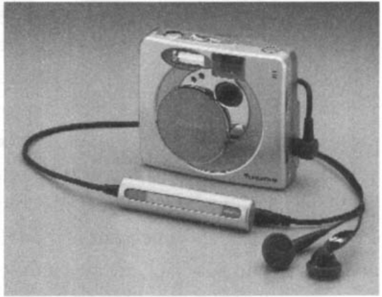

FIGURE 4.7a and b

Music everywhere.

While drilling holes or recharging batteries, while taking photographs, on your cell phone. And of course, while driving your car, jogging, Hying in an airplane, or just plain listening to music. Figure a shows the DEWALT battery charger for portable tools, with built-in radio; figure b shows an MP3 player built into a digital camera.

(Image a courtesy of DeWALT Industrial Tool Co. Image b courtesy of Fujifilm USA. Note: This model is no longer available.)

styles and hours of selections at every seat. Automobiles come equipped with radios and music players. And portable devices proliferate apparently endlessly, being either small and portable or combined with any other device the manufacturer thinks you might have

with you:watches, jewelry, cell phones, cameras, and even work tools (figure 4.7a & b). Whenever I have had construction work done on a home, I noted that, first, the workers brought in their music players, which they set up in some central location with a super-loud output; then they would bring in their tools, equipment, and supplies. DfiWALT, a manufacturer of cordless tools for construction workers, noticed the phenomenon and responded cleverly by building a radio into a battery charger, thus combining two essentials into one easy-tocarrybox.

The proliferation of music speaks to the essential role it plays in our emotional lives. Rhyme, rhythm, and melody are fundamental to our emotions. Music also has its sensuous, sexual overtones, and for all these reasons, many political and religious groups have attempted to ban or regulate music and dance. Music acts as a subtle, subconscious enhancer of our emotional state throughout the day.This is why it is ever-present, why it is so often played in the background in stores, offices, and homes. Each location gets a different style of music: Peppy, rousing beats would not be appropriate for most office work (or funeral homes). Sad, weepy music would not be conducive to efficient manufacturing.

The problem with music, however, is that it can also annoy-if it is too loud, if it intrudes, or if the mood it conveys conflicts with the listener's desires or mood. Background music is fine, as long as it stays in the background. Whenever it intrudes upon our thoughts, it ceases to be an enhancement and becomes an impediment, distracting, and irritating. Music must be used with delicacy. It can harm as much as help.

But if music can be annoying, what about the intrusive nature of today's beeping, buzzing, ringing electronic equipment? This is noise pollution gone rampant. If music is a source of positive affect, electronic sounds are a source of negative affect.

In the beginning was the beep. Engineers wanted to signal that some operation had been done, so, being engineers, they played a short tone. The result is that all of our equipment beeps at us. Annoying, universal beeps. Alas, all this beeping has given sound a

bad name. Still sound, when used properly, is both emotionally satisfying and informationally rich.

Natural sounds are the best conveyers of meaning: a child laughing, an angry voice, the solid "clunk" when a well-made car door closes. The unsatisfying tinny sound when an ill-constructed door closes. The "kerplunk" when a stone falls into the water.

But so much of our electronic equipment now bleats forth unthinking, unmusical sounds that the result is a cacophony of irksome beeps or otherwise unsettling sounds, sometimes useful, but mostly emotionally upsetting, jarring, and annoying. When I work in my kitchen, the pleasurable activities of cutting and chopping, breading and sauteing, are continually disrupted by the dinging and beeping of timers, keypads, and other ill-conceived devices. If we are to have devices that signal their state, why not at least pay some attention to the aesthetics of the signal, making it melodic and warm rather than shrill and piercing?

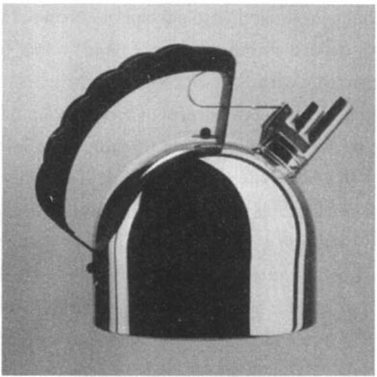

It is possible to produce pleasant tones instead of irritating beeps. The kettle in figure 4.8 produces a graceful chord when the water boils. The designers of the Segway, a two-wheeled personal transporter, "were so obsessed with the details on the Segway HT that they designed the meshes in the gearbox to produce sounds exactly two musical octaves apart-when the Segway HT moves, it makes music, not noise."

Some products have managed to embed playfulness as well as information into their sounds. Thus, my Handspring Treo, a combined cellular telephone and personal digital assistant, has a pleasant three-note ascending melody when turned on, descending when turned off. This provides useful confirmation that the operation is being performed, but also a cheery little reminder that this pleasant device is obediently serving me.

Cell phone designers were perhaps the first to recognize that they could improve upon the grating artificial sounds of their devices. Some phones now produce rich, deep musical tones, allowing pleasant tunes to replace jarring rings. Moreover, the owner can select the

FIGURE 4.8

Richard Sapper's kettle with singing whistle, produced by Alessi.

Considerable effort was given to the sound produced by the whistling spout: a chord of "e" and "b," or, as described by Alberto Alessi, "inspired by the sound of the steamers and barges that ply the Rhine."

(Alessi "9091." Design by Richard Sapper, 1983. Kettle with

melodic whistle. Image courtesy of Alessi.)

sounds, allowing each individual caller to be associated with a unique sound. This is especially valuable with frequent callers and friends. "I always think of my friend when I hear this tune, so I made it play whenever he calls me," said one cell phone user to me, describing how he chose "ring tones" appropriate to the person who was calling: joyful pleasant tunes to joyful pleasant people; emotionally significant tunes for those who have shared experiences; sad or angry sounds to sad or angry people.

But even were we to replace the grating electronic tones with more pleasant musical sounds, the auditory dimension still has its drawbacks. On the one hand, there is no question that sound-both musical and otherwise-is a potent vehicle for expression, providing delight, emotional overtones, and even memory aids. On the other hand, sound propagates through space, reaching anyone within range equally, whether or not that person is interested in the activity: The

musical ring that is so satisfying to a telephone's owner is a disturbing interruption to others within earshot. Eyelids allow us to shut out light; alas, we have no earlids.

When in public spaces-the streets of a city, in a public transit system, or even in the home-sounds intrude. The telephone is, of course, one of the worst offenders. As people speak loudly to make sure they are heard by their correspondent, they also cause themselves to be heard by everyone within range. Telephones, of course, are not the only intrusions. Radios and television sets, and the beeps and bongs of our equipment. More and more equipment comes equipped with noisy fans. Thus, the fans of heating and air-conditioning equipment can drown out conversation, and the fans of office equipment and home appliances add to the tensions of the day. When we are out of doors, we are bombarded by the sounds of passing aircraft, the horns and engine sounds of motor traffic, the warning back-up horns of trucks, the loud music players of others, emergency sirens, and the ever-present, shrill sounds of the cellular telephone ring, often mimicking a full musical performance. In public spaces, we are far too frequently interrupted by public announcements, starting with the completely unnecessary but annoying "Attention, Attention," followed by an announcement only of interest to a single person.

There is no excuse for this proliferation of sounds. Many cell phones have the option to set their rings to a private vibration, felt by the desired recipient but no others. Necessary sounds could be made melodious and pleasant, following the lead of the Sapper kettle in figure 4.8 or the Segway. Cooling and ventilation fans could be designed to be quiet as well as efficient by reducing their speed and increasing their blade size. The principles of noise reduction are well known, even if seldom followed. Whereas musical sounds at appropriate times and places are emotional enhancers, noise is a vast source of emotional stress. Unwanted, unpleasant sounds produce anxiety, elicit negative emotional states, and thereby reduce the effectiveness of all of us. Noise pollution is as negative to people's emotional lives as other forms of pollution are to the environment.

Sound can be playful, informative, fun, and emotionally inspiring. It can delight and inform. But it must be designed as carefully as any other aspect of design. Today, little thought is given to this side of design, and so the result is that the sounds of everyday things annoy many while pleasing few.

Seduction at the Movies

All the theatrical arts engage the viewer both cognitively and emotionally. As such, they are perfect vehicles to explore the dimensions of pleasure. In my research for this book, I discovered Jon Boorstin's analysis of films, a marvelous example of how the three levels of processing have their impact. His 1990 book, The Hollywood Eye: What Makes Movies Work, was such a wonderful fit to the analyses of my book that I just had to tell you about it.

Boorstin points out that movies appeal on three different emotional levels: visceral, vicarious, and voyeur, which bear perfect correspondence to my three levels of visceral, behavioral, and reflective. Let me start with the visceral side of movies. Boorstin's description of this component of a film is pretty much identical with my visceral level. Indeed, the match was so good, that I decided to use his term instead of "reactive," the term I use in my scientific publications. The phrase "reactive design" didn't quite capture the correct intention, but once I read Boorstin, it was obvious that the phrase "visceral design" was perfect, at least for this purpose. (But I still use "reactive" in my scientific publications.)

The passions aroused in film, says Boorstin, "are not lofty, they're the gut reactions of the lizard brain-the thrill of motion, the joy of destruction, lust, blood lust, terror, disgust. Sensations, you might say, rather than emotions. More complex feelings require the empathic response, but these simple, powerful urges reach up and grab us by the throat without an intermediary." He identifies the "slow-motion killing in The Wild Bunch, the monster in The Fly, or the bland titilla-

tion of soft-core porn" as examples of the visceral side of movies. Add the chase scene in The French Connection (or any classic spy or detective story), gun battles, fights, adventure stories, and,of course, horror and monster movies, and you have classic visceral level adventures.

Note the critical role played by music and lighting: dark, creepy scenes and dark, foreboding music. Minor keys for sad or unhappy, jubilant bouncy melodies for positive affect. Bright colors and bright lighting versus dark, gloomy colors and lights all exert their visceral influence. Camera angle, too, exerts its influence. Too far away, and the viewer is no longer experiencing but, instead, observing vicariously. Too close, and the image is too large for direct immediate impact. Film from above, and the people in the scene are diminished; film from below, and the actors are powerful, imposing. These operations all work on the subconscious level. We are usually unaware of the techniques used by directors and photographers to manipulate our emotions. The visceral level becomes completely absorbed in the sights and sounds. Any awareness of the technique would occur on the reflective level and would distract from the visceral experience. In fact, the only way to critique a film is by becoming detached, removed from visceral reaction and able to ponder the technique, the lights, the camera movements and angles. It is difficult to enjoy the film while analyzing it.

BOORSTIN'S "VICARIOUS" level corresponds to my "behavioral" level. The word "vicarious" is appropriate because the viewers are not directly engaging in the filmed activities but are, instead, watching and observing. If the film is well crafted, they are enjoying the activities vicariously, experiencing them as if they were participating. As Boorstin says, "The vicarious eye puts our heart in the actor's body: we feel what the actor feels, but we judge it for ourselves. Unlike relationships in life, here we can give ourselves up to other people in full confidence that we will always be in command."

If the visceral level grabs the viewer in the guts, driving automatic reactions, the vicarious level involves the viewer in the story andemotional line of the movie. Normally, the behavioral level of affect is invoked by a person's activities: it is the level of doing and acting. In the case of a film, the viewer is passive, sitting in a theater, experiencing the action vicariously. Nonetheless, the vicarious experience can play upon the same affective system.

Here is the power of storytelling, of the script, the actors, transporting viewers into the world of make-believe. This is "the willful suspension of disbelief" that the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge discussed as being essential for poetry. Here is where you get captured, caught up in the story, identifying with the situation and the characters. To be fully engrossed within a movie is to feel the world fade away, time seem to stop, and the body enter the transformed state that the social scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has labeled "flow."

Csikszentmihalyi's flow state is a special, detached state of consciousness, in which you are aware only of the moment, of the activity, and of the sheer enjoyment. It can occur in almost any activity: skilled tasks, sports, video games, board games, or any kind of mind-absorbing work. You can experience it in the theater, reading a book, or with intense problem solving.

The conditions required for flow to occur include lack of distractions and an activity paced precisely to match your skills, pushing you slightly above your capabilities. The level of difficulty has to be just at the edge of capability: too difficult and the task becomes frustrating; too easy and it becomes boring. The situation has to engage your entire conscious attention. This intense concentration causes outside distractions to fade away and the sense of time to disappear. It is intense, exhausting, productive, and exhilarating. It is no wonder that Csikszentmihalyi and his colleagues have spent considerable time exploring the phenomenon in its many manifestations.

The key to success of the vicarious level in film is the development and maintenance of the flow state. The pace has to be appropriate to

avoid frustration or boredom. There can be no interruptions or distractions that might divert attention if one is to become truly captured by flow. Whenever we speak of films or other entertainment as "escapist," we are referring to the ability of the vicarious state and the behavioral level of affect to disengage people from the cares of life and transport them into some other world.

THE VOYEURISTIC level is that of the intellect, standing back to reflect and observe, to comment and think about an experience. Here is where the depth and complexity of characters, events, and the metaphors and analogies that a movie is meant to convey produce a deeper, richer meaning than is visible on the surface with the characters and story. "The voyeur's eye,"says Boorstin, "is the mind's eye, not the heart's."

The word "voyeur" often is used to refer to observation of sensual or sexual subjects, which is not the meaning intended here. Boorstin explains that by the term "voyeur," he means "not the sexual kink but Webster's second definition of the word: the voyeur is the 'prying observer.' The voyeur's pleasure is the simple joy of seeing the new and the wonderful."

The voyeur's eye demands explanation-this is the level of cognition, of understanding and interpreting. As Boorstin points out,the vicarious experience can be profoundly moving, but the voyeur'seye, ever watching, ever thinking, is logical and reflective: "The voyeur in us is logical to a fault, impatient, picky, literal, but if properly respected it gives the special pleasures of the new and the clever, of a fresh place or crisply thought-out story." Of course, the voyeur can generate emotional suspense as well. It is the voyeur who knows that the wicked villain is hiding in wait for the hero, that the trap seems inescapable, and therefore that the hero is about to face death or, at the least, pain and torture. This level of excitement requires the thinking mind, and, of course, a clever director who plays upon those conjectures.

But, as Boorstin also points out, the voyeur can ruin a perfectly good movie by critiquing it:

It can ruin the most dramatic moment with the most mundane concern: "Where are they?" "How did she get in the car?" "Where did the gun come from?" "Why don't they call the police?" "He's already used six shots-how come he's still firing?" "They'd never get there in time!" For a movie to work, the voyeur's eye must be pacified. For a movie to work brilliantly, the voyeur's eye must be entranced.

Voyeuristic movies are reflective movies, for example 2001: A Space Odyssey, which, except for one lengthy visceral section, is mindnumbing in its intellectualism and almost exclusively a reflective experience. Citizen Kane is a fine example of both an entrancing story and a voyeur's delight.

JUST AS our experiences do not come neatly divided into unique categories of visceral, behavioral, or reflective, so films cannot be stuck neatly into one of three packages: visceral, or vicarious, or voyeuristic. Most experiences, and most films, cut across the boundaries.

The best products and the best films neatly balance all three forms of emotional impact. Although The Magnificent Seven is, as Boorstin puts it, "seven guys saving a town from bandits," if that were all there was to it, it would not have become such a classic. The film started life in 1954 in Japan as The seven samurai (Shichinin no samurai), a film directed by Akira Kurosawa. In Japan, it was the story of seven samurai warriors hired to save a village from murderous thieves. It was redone as an American western in 1960 as The Magnificent Seven by John Sturges. Both films follow the same story line (both are excellent, although many movie buffs prefer the original). And both films successfully capture the viewer at all three modes, with engaging visceral spectacles, an engrossing story for the

vicarious, and enough depth and hidden metaphorical allusions to content the reflective voyeur.

Sound, color, and lighting also play critical roles. In the best of cases, they heighten the experience without conscious awareness. Background music, on the face of it, is strange, for it is present even in so-called realistic movies, even though no music plays in our everyday world of real life. Purists scoff at the use of music, but omit it and a movie suffers. Music seems to modulate our affective system to enhance the experience at all levels of involvement: visceral, vicarious, and voyeuristic.

Lighting can intensify experience. Although most films today are shot in color, the director and photographer can dramatically impact the film by the style of lighting and color. Bright primary colors are the one extreme, with subdued pastels or dimly lit scenes another. The extreme case of color is the decision not to use it: to film in black and white. Although rarely used anymore, black and white can convey powerful dramatic impact, quite different from that possible with color. Here, the cinematographer can make skillful use of contrastslight and dark, subtle grays-to convey an image's emotional tone.

The craft of filmmaking encompasses a wide variety of domains. All elements of a film make a difference: story line, pace and tempo, music, framing of the shots, editing, camera position and movement. All come together to form a cohesive, complex experience. A thorough analysis can, and has, filled many books.

All these effects work best, however, when they are unnoticed by the viewer. The Man Who Wasn 't There (directed and written by the Coen brothers) was filmed in black and white. Roger Deakins, the cinematographer, stated that he wanted black and white rather than color so as not to distract from the story; unfortunately, he fell in love with the power of monochrome images. The film has wonderfully glorious shots, with high dark/light contrast, and in some places spectacular backlighting, all of which I noticed. This is a no-no in film: if you notice it, it is bad. Noticing takes place at the reflective (voyeur's) level, distracting you from that suspension of disbelief so

essential to becoming fully captured by the flow at the behavioral (vicarious) level.

The story line and engrossing exposition of The Man Who Wasn 't There enhanced the vicarious pleasure of the film, but noticing the photography caused the voyeuristic pleasure to interrupt with internal commentary ("Howdid he do that?" "Look at the magnificent lighting," and so on) and throw the vicarious pleasure off track. Yes, you should be able to go back afterward and marvel at how a film was done, but this should not intrude upon the experience itself.

Video Games

Overslept, woke at 8:00. Only time for a quick coffee before the carpool arrives. The kitchen is disgusting, didn't clean up after last night's little party. Need a bath, but no time (the bathroom's flooded anyway from the broken sink I never got around to fixing). Got to work late and in horrible shape, was demoted as a result. Got home at 5:00,the repo man promptly showed up and repossessed my television because I forgot to pay my bills. My girlfriend won't speak to me because she saw me flirting with the neighbor last night.

Did you realize that this quotation is the description of a game? Not only does it feel like real life, but a bad life at that. Why would anyone think it was a game? Aren't games supposed to be fun? Well, not only is it a description of a game, it is a best-selling one called "The Sims." Will Wright, the designer and inventor of the Sims, explained that this was a typical day in the life of a game character, as developed by a beginning player.

The Sims is an interactive simulated-world game, otherwise known as a "God" game or sometimes "simulated life." The player acts like a god, creating characters, populating their world with houses, appliances, and activities. In this game, the player does not control what the game characters do. Instead, the player can only set up the environ-

ment and make high-level decisions. The characters control their own lives, although they have to live within the environment and high-level rules established by the player. The result is quite often not at all what their god intended them to do. The quotation is one example of a character unable to cope within the world its god created. But, says Wright, as the player's skill at creating worlds improves, the character might be able to spend the end of each day "sipping mint-juleps by the pool."

Wright explains the problem like this:

The Sims is really just a game about life. Most people don't consciously realize how much strategic thinking goes into everyday, minute-to-minute living. We're so used to doing it that it submerges into our subconscious as a background task. But each decision you make (which door to go through? where to eat lunch? when to go to bed?) is calculated at some level to optimize something (time, happiness, comfort). This game takes that internal process and makes it external and visible. One of the first things players usually do in the game is to recreate their family, home, and friends. Then they're playing a game about themselves, sort of a strange, surreal mirror of their own lives.

Play is a common activity, engaged in by many animals and, of course, by us humans. Play serves many purposes. It probably is good practice for many of the skills required later in life. It helps children develop the mix of cooperation and competition required to live effectively in social groups. In animals, play helps establish their social dominance hierarchy. Games are more organized than play, usually with formal or, at least, agreed-upon rules, with some goal and usually some scoring mechanism. As a result, games tend to be competitive, with winners and losers.

Sports are even more formally organized than games, and at the professional level, are as much for the spectator as the player. As a result, an analysis of spectator sports is somewhat akin to that of movies, where the experience is vicarious and as a voyeur.

Of all the varieties of play, games, and sports, perhaps the most exciting new development is that of the video game. This is a new genre for entertainment: literature, film, game playing, sports, interactive novel, storytelling-all of these, but more besides.

Video games were once thought of as a mindless sport for teenage boys. No more. They are now played all around the world, including slightly more than half the population of the United States. They are played by everyone: from children to mature adults, with the average age of a player around thirty, and the gender difference evenly split between men and women. Video games come in many genres. In The Medium of the Video Game, Mark Wolf identifies forty-two different categories:

Abstract, Adaptation, Adventure, Artificial Life, Board Games, Capturing, Card Games, Catching, Chase, Collecting, Combat, Demo, Diagnostic, Dodging, Driving, Educational, Escape, Fighting, Flying, Gambling, Interactive Movie, Management Simulation, Maze, Obstacle Course, Pencil-and-Paper Games, Pinball, Platform, Programming Games, Puzzle, Quiz, Racing, Role-Playing, Rhythm and Dance, Shoot 'Em Up, Simulation, Sports, Strategy, Table-Top Games, Target, Text Adventure, Training Simulation, and Utility.

Video games are a mixture of interactive fiction with entertainment. During the twenty-first century, they promise to evolve into radically different forms of entertainment, sport, training, and education. Many games are fairly elementary, simply putting a player in some role where fast reflexes-and sometimes great patience-are required to traverse a relatively fixed set of obstacles in order to move up the levels either to obtain a total game score or to accomplish some simple goal ("rescue the beleaguered princess and save her kingdom"). But wait. The story lines are getting ever-more complex and realistic, the demands upon the player more reflective and cognitive, less visceral and fast motor responses. The graphics and sound are getting so good that simulator games can be used for real

training, whether flying an airplane, operating a railroad, or driving a race car or automobile. (The most elaborate video games are the full-motion airplane simulators used by the airlines that are so accurate that they enable pilots to be certified to fly passenger planes without ever flying the actual aircraft. But don't call these "games"; they are taken very seriously, and some of them can cost as much as the airplane itself.)

Today's sales of video games approach-and, in some cases, surpass-box-office receipts of movies. And we are still in the early days of video games. Imagine what they will be like in ten or twenty years. In an interactive game what happens in a story depends as much upon your actions as on the plot set up by the author (designer). Contrast this with a movie, where you have no control over the events. As a result, when experienced game players watch a movie, they miss this control, feeling as if they are "stuck watching a one-way plot." Moreover, the sense of involvement, the flow state, is much more intense in games than in most movies. In movies, you sit at a distance watching events unfold. In a video game, you are an active participant. You are part of the story, and it is happening to you, directly. As Verlyn Klinkenborg says, "what underlies it all is that visceral sense of having walked through a door into another universe."

The interactive, controlling part of video games is not necessarily superior to the more rigid, fixed format of books, theater, and film. Instead, we have different types of experiences, both of which are desirable. The fixed formats let master storytellers control the events, guiding you through the events in a carefully controlled sequence, very deliberately manipulating your thoughts and emotions until the climax and resolution. You surrender yourself quite voluntarily to this experience, both for the enjoyment and for the lessons that might be learned about life, society, and humanity. In a video game, you are an active participant, and as a result, the experience may vary from time to time-dull, boring, frustrating during one session; exciting, invigorating, rewarding during another. The lessons to be learned will vary depending upon the exact sequence of events that occurred and

whether or not you were successful. Books and films clearly have a permanent role in society, as do games, video or otherwise.

Books, theater, movies, and games all occupy a fixed period of time: there is a beginning, then an end. This is not so of life. Sure, birth marks the beginning and death the end, but from your everyday perspective, life is ongoing. It continues even when you sleep or travel. Life cannot be escaped. When you go away, you return to find out what has transpired in your absence (during those moments when you were not in touch via messaging, email, or telephone). Video games are becoming like life.

Video games used to involve single individuals. This will always be a viable genre, but more and more, these games are involving groups, sometimes scattered across the world, communicating through computer networks. Some are on-line, real-time activities, such as sports, games, conversations, entertainment, music, and art. But some are environments, simulated worlds with people, families, households, and communities. In all of these, life goes on even when you, the player, are not present.

Some games have already tried to reach out toward their human players. If you, the player, create a family in a "god" game, nurturing your invented characters over an extended duration, perhaps months or even years, what happens when a family member needs help while you are asleep, or at work, school, or play? Well, if the crisis is severe enough, your game-family member will do just what a real family member would do: contact you by telephone, fax, email, or whatever form works. Someday one might even contact your friends, asking for help. So don't be surprised if a co-worker interrupts you in an important business meeting to say that your game character is in trouble: it is in urgent need of your assistance.

Yes, video games are an exciting new development in entertainment. But they may turn out to be far more than entertainment. The artificial may cease to be distinguishable from the real.

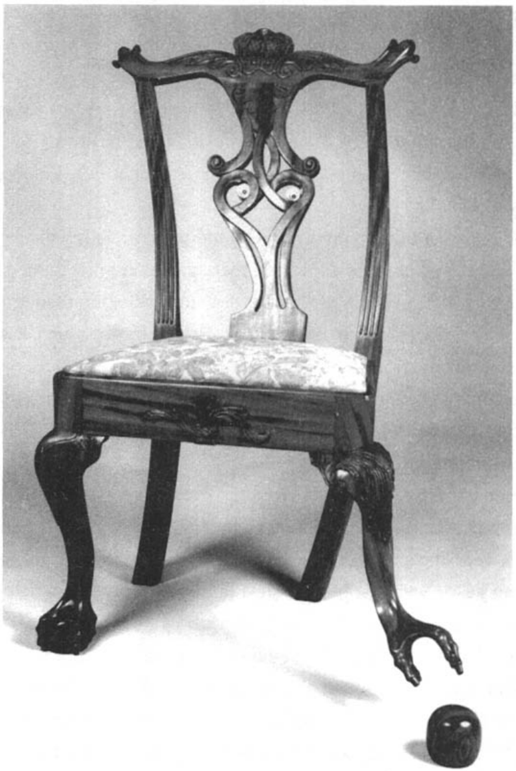

FIGURE 5.1

Oops! Uh oh, the poor chair.

It lost its ball, and it doesn't want anyone to know! Look how quietly it's sneaking out its foot, hoping to get it back before anyone notices.

(Renwick Gallery; image courtesy of Jake Cress, cabinetmaker.)