sell to your first hundred customers

It just took off. A true viral success.

NO ONE, EVER

After building a product, many people think the next step is launching it to the world. Hollywood has premiere parties, while Silicon Valley has Demo Days, Product Hunt launches, and 'Show HN' posts.

This obsession with launching is not exclusive to Hollywood and Silicon Valley. It pervades the thinking of cities and towns throughout the world. There's probably a restaurant near you with a giant red sign pinned over its entrance reading grand opening.

It invites you in, with a promise that you'll be one of the first. Maybe you'll get a deal. But tomorrow, and even a month from now, the sign is still there. They're always opening, and grandly too!

Lots of businesses go this route. Jeffrey Katzenberg, cofounder and former CEO of Dreamworks, and Meg Whitman, former CEO of eBay, founded streaming video service Quibi, a cautionary tale of launching before actually going to market. The company raised $1.8 billion and bought Super Bowl ads, expecting the whole world to flock to their service. It planned a launch party, meant to draw 150 celebrities among its 1,500 guests, that was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ultimately, the app bombed. Only 300,000 people downloaded Quibi on day one, compared with Disney+'s 4 million. One month post-launch, Quibi had fallen off the Top 100 chart, and within six months it shut down and returned its investors' money.

This experience isn't so different for software businesses. Two excitable cofounders work on an app, submit it to Product Hunt, and see thousands of sign-ups on the first day. A few months later, no one is using it, and they're on to a new project. Rinse and repeat. But businesses are not something you engage with once, talk to your friends about, and then forget as you move on to the next thing. Your business should have customers for life, not just for a Friday night.

That's because the real story of starting and then growing a business isn't really that thrilling most days. Between start and success, it can be a slog. It can take years. And it often isn't nearly as glamorous as you expect. But you will have many small victories, and over time they will build into a sense of satisfaction and pride that comes from not giving up.

In the last chapter we focused on process and product, but once you have your MVP, it's time to turn your attention to your first customers. If you wait too long, if you endlessly iterate without showing your work to the world, you may feel productive even though you are slowly (or quickly) running out of runway.

That's why it's so important to start. Once you have enough repeat customers, you have product-market fit, which is a milestone worth celebrating and a sign you can think about launching. Until then, skip the one-time grand opening, and instead focus on the slow and steady journey of selling to your first hundred customers.

Sales Is Not a Four-Letter Word

I interviewed a lot of people for this book, and you wouldn't believe how hard it was to get anyone to talk about sales. No one likes the stereotype idea of selling-it's sleazy, and it depends on information asymmetry-but that is not what we are doing here. You already have a relationship with the community, and you're selling a product that adds value to the life of a customer who is happy to pay for it.

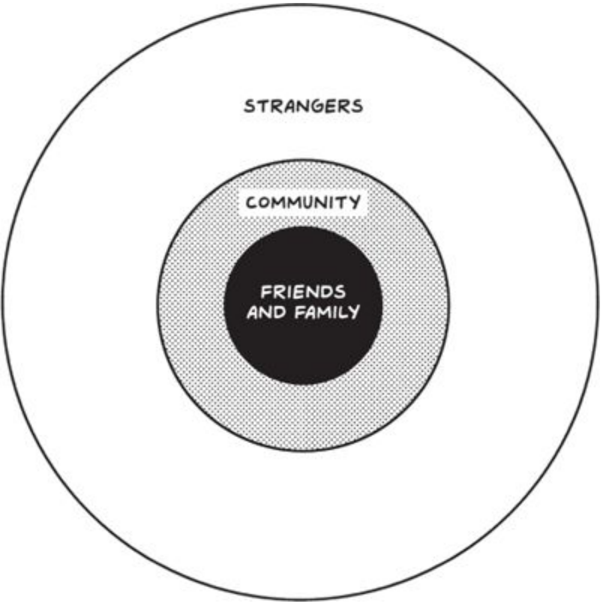

Eventually strangers will buy your product, but mostly because your customers are spreading the gospel of your business and product, not because they saw an ad. But it will take time to get there. It's not something you hit on day one.

Look at your own life: When was the last time you went on Twitter or Facebook and shouted from your digital balcony about a product you loved? It just doesn't happen that often.

'Viral success' is a myth, pure and simple. There is no such thing. It's just something journalists say about a person, company, product, or service whose seemingly rapid rise is inexplicable from the outside. Most of usand that includes journalists-only notice new things when they've reached escape velocity. We're often unaware of the previous months or years of hard work and stumbles.

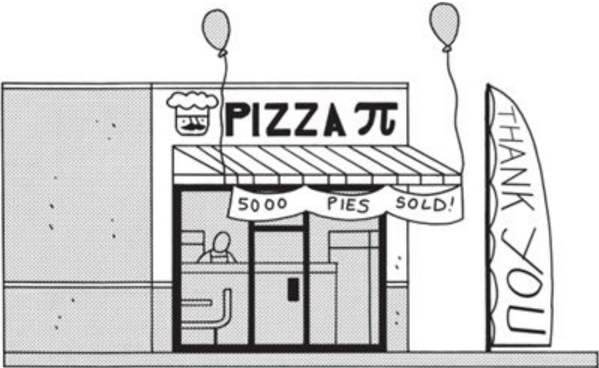

At the end of this chapter, you will launch, but it's because you'll be celebrating milestones that will actually mean something about the longevity and sustainability of your business. You will be profitable, you will have customers paying for your product, and they will be telling other customers about it. Then you can launch-or rather, you can celebrate by saying thank you to the community and the customers who have helped you build from nothing to something.

Until then, treat the sales process as an opportunity for discovery. You think your product is market-ready. It's probably not. You think you've figured out the correct pricing tiers. You probably haven't.

Turn every failed conversion into an insight. Either you're talking to the wrong person and you need to shift your focus, or they're the right person but your product still has work to do to solve their problem. Both are good learnings, learnings you want to have before you start marketing to a broader audience.

For now, sales is an education process. Your customers will get to know you, and you'll get to know what's working, what's not, and how to fix it. Selling might not always go smoothly at the beginning, but I guarantee waiting won't make it any easier. Once you've figured out how to get started, the next challenge is pricing.

Charge Something, Anything

Pricing is hard. In the early days, you may be tempted to give your product away for free or to charge less than the value of your time or the raw materials you used. Don't. In order to stay alive, you need to make money. The only way to do that is not only to charge something, but to charge something that allows you to stay afloat. If you've productized, then you've already figured out an initial pricing structure for your first customers, and pricing, just like every other part of a business, is subject to iteration. Eventually, the type of customer you have will influence how and how much you charge, but at the beginning, as you build your solution, keep in mind that you're able to charge in two ways:

- Cost-based (things that have inherent costs-for example, web servers or an employee's time). If you need to pay a certain amount, you can add a 'margin,' say 20 percent, and charge that. For example, retail stores often buy wholesale and double the price when they sell it to consumers (giving them a margin of 50 percent). Marketplaces such as iTunes or iStockPhoto often go with this method.

- Value-based (a feature with clear value). This is charging for something not because it costs you money to deliver, but because it has inherent value for the customer. For example, Netflix may have a multiscreen feature that doesn't cost them any money to provide (beyond the engineering costs to ship the feature in the first place), but they are able to charge a monthly fee for it.

The goal is to eventually charge people for tiered levels of service, which you can do when your product, service, or software has an established value and brand. Think of the tiers as you would think of the different types of plane tickets-you'll get to your destination whether you sit in economy, business class, or first class, but with substantially different levels of service. Tiered pricing is a common practice for most software businesses, and it changes all the time depending on the features offered.

For example, Circle.so, a community platform for creators, has three levels of service, basic, professional, and enterprise, based both on the number of members in the community and on available features and integrations.

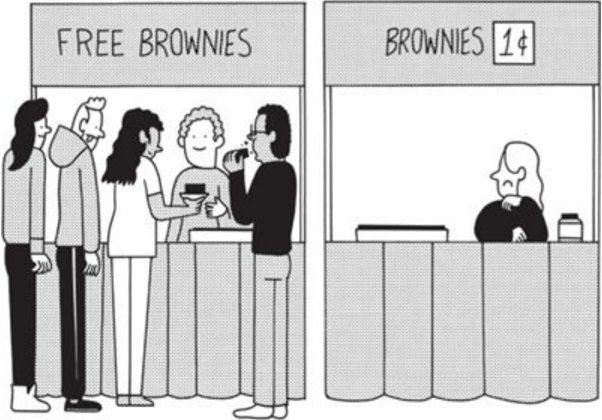

Even if you start low and go up over time, it is important to charge something. There is a very large difference between free and one dollarthat's the zero price effect . As behavioral economist Dan Ariely writes in Predictably Irrational , 'people will jump for something free even when it's something they don't want.' He uses the example of a long line of college students waiting for free, terribly unhealthy brownies. Asked to pay even just one cent, the line of kids disappears.

(Later, you can consider introducing a free tier. This model, popularized by venture capitalist Fred Wilson, is often referred to as 'freemium.')

Advertising-driven media models are another example. When the reader doesn't pay anything, it's often hard to convince them that it's valuable when the time comes to start charging for it.

Pricing decisions are not permanent. A price is just a part of a product, like everything else, and it can and will change over time. Similar to product development, your goal is to start the discovery process, not get to the perfect result right away.

It's worth noting that when prices for products do change, they generally go up. This should be true for you as well: As your product improves and you are able to provide a better service, your offering will become more valuable to your customer as well-and you may even introduce higher tiers for your superusers.

Once you've picked a price, you need to shop it around. I recommend starting with those closest to you: your friends and family.

(Unfortunately, not everyone has a supportive family. Feel free to substitute a chosen family in its place.)

Friends and Family First

In Silicon Valley, there's a term for the first round of funding: the 'friends and family' round. This may be even more common outside the Bay Area, where venture capitalists and angel investors do not patrol the streets looking for things to fund. But friends and family aren't just important when it comes to funding. Whether or not they've given you a dime up until now, it's worth pitching them to be your first customers.

This may make you uncomfortable even if you know that friends and family are in the dead center of your community. It certainly made me uncomfortable, shoving my business in my friends' faces and asking them to try Gumroad when I knew I didn't have all the kinks worked out yet. But when you're just getting started, with few credentials to your name, who trusts you more than your friends and family? And if they don't, who will?

Yet people believe they can skip their friends and family in favor of launching and going viral. For example, on Kickstarter. But even Kickstarter knows this isn't the case. 'Millions of people visit Kickstarter every week, but support always begins with people you know,' it reads on their website. 'Friends, fans, and the communities you're a part of will likely be some of your earliest supporters, not to mention your biggest resources for spreading the word about your project.'

Projects do go viral occasionally, I'm sure, but virtually none without a big initial push from the friends, family, and fans of the project's creators.

All of that is to say it's normal and maybe even expected to rely on friends and family to provide initial support, and to be the first to buy your product. If you're having trouble with that, remind yourself you've built something you think provides real value. It's worth paying for even if it's not perfect!

PleaseNotes founder and CEO Cheryl Sutherland was using journaling and affirmations to uncover her next professional step when she came up with the idea for her company, which offers coaching programs and makes journals and other products geared toward personal development. A close friend who was a graphic designer helped design her website and her first product, the PleaseNotes, a set of three sticky notepads printed with affirmations. Two other friends who had a crowdfunding consulting business advised her on how to launch an effective Kickstarter campaign to generate preorders for her second product, a PleaseNotes journal. Her goal was to raise $10,000. She eventually raised $15,054 from 253 people, many of whom were friends and family. That money allowed her to test the market and gave her the momentum she needed to keep going.

That early proof of concept is invaluable. It takes time for a restaurant to figure out their menu, hence soft openings with friends and family. It takes time for a movie to figure out its pacing, hence test screenings. The same goes for your business and your product.

Once you've addressed feedback and turned your friends and family into customers because your product is genuinely good, you can move on from your friends and family, and into your communities.

Community, Community, Community

Over time, this becomes less about you and more about your product . Your friends and family, whom you started with, cared most about you. Your community cares less about you and more about your product.

This is the same way your business grows: starting with the people who care about you the most, and 'ending' with the people who care about you the least.

Even if you've successfully solved a problem for your community, it may take some time and patience to get their attention. Humans, like objects, have inertia. Everyone is on a path, and it usually takes a bump to knock them in a different direction, even if it is a better one in the form of the solution you're offering with your business.

Beyond the other human beings you personally know or are connected to, you can seek out similar customers in the physical environment around you. Every neighborhood, street, and downtown is a community where people live together and hang out. In thriving communities, there are local businesses, event venues, and block parties. This is where life happens outside of the office and the home. Put a poster on the wall of your favorite coffee shop and on telephone poles.

In the next chapter we'll talk about formal marketing, but long before you ever implement a more structured plan, you can still take advantage of opportunities for strategic outreach. Every community has reporters and micro-influencers, who cover the goings-on within the community. In Portland, where I live now, there are dozens of Instagram and Twitter accounts about every facet of the city. These are student, amateur, and professional journalists. They live to write about what you are up to.

This is how you make that happen:

-

- Make a list of everyone-yes, everyone-who has written or shared anything about a similar business. A business launch. A business closure. A new product launch. A date night at that business. We can call these people subject matter experts .

-

- Contact them all personally. Offer to walk them through your product, or meet them at your store, or give them a free meal. With Gumroad, I did this literally hundreds of times. And thousands of creators later, if I see a creator I really like whom I think Gumroad could help, I still reach out.

-

- Ask for their personal, candid feedback. Do not ask for reviews, or a social media post, or for them to tell their friends. Your goal is to improve your product experience, and you should make it clear that you massively appreciate their support.

When you first bring your product to market, you may be part of one community, but that community will grow and change as your business grows and changes. It's simply discovering additional points of overlap and need and letting a broader group know that you have come up with a new solution to their problem. And hopefully, your customers will develop into their own community over time.

This is about building relationships. You will be doing business for a long time, and it is much easier to keep a customer than to find a new one. Never oversell. Be honest, open, and always kind. Show them how you most recently improved your product. Tell them a recent failing. Don't sell them on your product, educate them on your journey and learnings.

Cold Emails, Calls, and Messages

Long before you get to the bottom of the list of people you already know or could know, you're going to be sending a lot of emails, you're going to be making a lot of calls, and you're going to be knocking on a lot of doors. It's your job to reach out to friends, family, and members of your community whom you may not have seen for a while. Your calls are a chance to tell them what you're up to and ask them if they're interested in becoming customers. Some will say yes, but many will say no. Once you're okay with the nos, you're ready to sell to strangers.

In the early days (read: years) of Gumroad, we scoured the web for people who could benefit from a product like Gumroad and then told them about it. Literally thousands of times. That's the only way, really, when you're young and no one cares or knows who you are, to get folks to use your product.

Over time, you can get away with doing it less and less. But until you have a lot of customers or some other force that can supply ongoing momentum, there's nothing better than knocking on doors. This is a triedand-true technique used by political canvassers, the LDS Church, and others . . . because it works! Trust me, if there was a better way, people would have found it.

Even Katrina Lake, CEO of Stitchfix and one of Forbes 's Richest SelfMade Women in 2020, started out with cold calls and cold messages on LinkedIn to potential investors. 'The more shameless you can be, the thicker skin you have, the better,' she says. 'People are going to not write back and people are going to say no, but every now and then someone's gonna be interested and say yes. And you wouldn't have had that chance if you hadn't gotten all the no's first.' While you may not be hitting up investors, you will be talking to people over and over again who will say no. The sooner you get used to it, the sooner you stop taking it personally and use those nos as a learning opportunity, the better.

I get it. It's awkward and uncomfortable to reach out to people you don't necessarily know personally, many of whom will ignore or reject you. My sense is that people who wish to reach customers some other way, like search engine optimization (SEO) or content marketing, are looking for an out. If that's you: Stop! It doesn't exist! Just hunker down and dedicate some time to finding people, reaching out to them personally via email, phone, whatever, and being okay with it sucking for a while. You may find that talking about your process and your product and the path you've taken to get there is far less difficult than you think. After all, this is your work, and if you're bringing it out to the world, you should be excited and proud, so don't skip this chance at discovery.

A stellar launch doesn't change this. Fanfare doesn't bring real customers, as Quibi learned. Consistent growth comes after a long period of time, mostly driven, especially at the beginning, by a hardworking sales team-starting with you.

If you need help getting started, here's an example:

Hi John,

I saw you're selling a PDF on your website using PayPal, and manually emailing everyone who buys the PDF. I built a service called Gumroad, which basically automates all of this. I'd love to show it to you, or you can check it out yourself: gumroad.com.

Also happy to just share any learnings we see from creators in a little PDF we have. Let me know!

Best, Sahil, founder and CEO of Gumroad

Don't copy-paste. Each email will refine your ability to write better emails. Done right, you're not only educating customers, but educating yourself about what you can do better. It's a learn-learn situation.

Manual 'sales' will be 99 percent of your growth in the early days, and word of mouth will be 99 percent of your growth in the latter days. It's not a glamorous answer, but it's true. Things like paid marketing, SEO, and content marketing can come later, once you have a hundred customers, once you're profitable, and once your customers are referring more customers to you. Only then!

The best news of all is that once you have a hundred customers, you can use the same playbook to get to a thousand. Once you have a thousand, you can use a similar playbook to get to ten thousand.

When Slack IPO'd in 2020 at a valuation of $16 billion, its offering documents showed that 575 of their customers accounted for approximately 40 percent of their revenue. This just goes to show that you need far fewer customers than you may think.

Big network-focused tech companies boast dazzling metrics, but their actual profits (when they have profits, anyway) come from a very tiny portion of their total audience. The rest of us might do better to ignore the lurkers and freeloaders altogether and focus on core customers. Depending on the nature of the product or service, anywhere from a few dozen to a few thousand regular customers will be more than enough to keep a business viable long-term.

Mailchimp is a good example of how focusing on smaller, reliable customers might make more sense than swinging for the fences. Ben Chestnut and Dan Kurzius first started a web design agency called the Rocket Science Group with a focus on big corporate clients, but at the same time they also built Mailchimp, an email marketing service for small businesses. For about seven years they ran both businesses, until they closed the web design agency in 2007 because they found that working for small businesses gave them the freedom to be more creative and adapt quickly to their customers' needs.

Chestnut and Kurzius have a universe of offerings, but Mailchimp's service is free up to the first two thousand emails. Once customers want to send to a larger list or need extra services, their plans begin at $10 per month and go up from there (see the earlier conversation on tiered pricing!). Even though Mailchimp could broaden its reach to corporations or institutions, the company's customer base is still small businesses, and they've not strayed from their mission to build out features for their core community.

It may be surprising, but it is not a coincidence. Whether you're just starting or you've been in business for years, your most important clients are your community. They trust you because you've helped them grow their own businesses. It's not happenstance that they're ready to support you when you have your own.

This isn't just about huge SaaS businesses either. It applies to smaller businesses too. Across the spectrum of minimalist entrepreneurs, I see a common pattern: manual sales, finding your community, talking about your journey, highlighting your customers, and getting authentic coverage. If you started with community, and you continue to pay attention and solve the persistent problems your community has, then those first customers can take you very far.

Growth-at-all-costs is all about selling to strangers so that you can scale, but profitability-at-all-costs means you don't need to depend on strangers to keep your business afloat. Instead, you can rely on your existing customers from your communities and eventually from your audience. They'll spread the word as they feel comfortable doing so, and that's how you'll grow. The math looks different for everybody, but the goal is the same: financial independence. When I did it for myself, I needed about $2,000 a month to maintain my lifestyle.

If your product costs $10 a month, like Gumroad's, you need two hundred customers. That doesn't seem so bad. There are about 260 business days a year, so you'd get there in less than a year if you acquired one customer every business day.

Daniel Vassallo tweeted recently:

Daniel Vassallo @dvassallo Dec 30, 2019

- You don't need to dominate the market .

- You don't need to disrupt anything.

- You don't need to conquer the competition;

You can add 1 new customerlday & before you know it; you'll have a $IMJyr machine Wouldn't that be enough?

- 144 1.2K

That doesn't sound so hard, does it? You may already be selling a product for someone else for your day job. Sell your own!

Sell Like Jaime Schmidt

Jaime Schmidt never launched Schmidt's Naturals, a natural deodorant brand she founded in 2010. Instead, she celebrated small milestones along the way before eventually selling her company for more than $100 million in 2017 to Unilever.

When Jaime was pregnant with her son, she started a deep dive into the world of natural personal care products after taking a class in DIY shampoo. While there were hundreds of recipes available for soaps and lotions, there were few, if any, recipes for deodorants even though many people were concerned about ingredients in traditional formulations. Jaime had tried all of the natural deodorants but had found that none of them worked for her, so she decided to make one herself. She experimented for months until she found an effective formulation and landed on a scent, cedarwood, that she loved. Six months after the shampoo class, she had a product line of lotions and deodorant, and she was ready to sell to her first customers.

She set up a simple website and a Facebook page for her business where she posted articles and recipes. In the first few months, she sold her products on consignment at two small local goods stores in Portland and on her own at a few street fairs and farmer's markets around the city. People stopped at her booth to try the deodorant and lotions, and she found a rhythm to her conversations with prospective customers: asking them about the products they used; talking about her products and how she had tested them; and convincing people that her natural deodorant actually worked.

The following year, she decided to go all-in on her idea. She took two part-time positions with stores that sold Schmidt's, a decision that served a dual purpose. First, interacting with the clientele gave her a chance to gather customer insights about her own products and learn about the inner workings of retail. But just as important, the income from those gigs served as the seed money to get Schmidt's off the ground. The in-store customers as well as the people she continued to meet at festivals and fairs were most enthusiastic about the deodorant she made; many times, they returned to tell her how well it worked and to buy more. She says, 'Early customer feedback allowed me to perfect my formula, determine future scents, and recognize where I was making the most impact.' And once she had refined her deodorant, 'customers gave me validation that my product worked astonishingly well, and they spread the word.'

Schmidt started 2012 with new, modern packaging for the deodorant, which was designed to set it apart from the competition. She looked beyond the direct-to-consumer sales channels and the natural and wellness retailers that her competitors used almost exclusively; in 2015, she expanded into traditional grocery stores and pharmacies, which allowed her to reach more customers and to enable greater access to healthy natural products.

Her creativity, innovation, and hard work paid off. Schmidt earned appearances on Fox News and The Today Show ; mentions on social media from celebrities and influencers; articles in national publications; and distribution on the shelves of Target and Walmart. Though it was bittersweet, Jaime realized that a larger company with more resources could bring her vision and mission to an even wider customer base, and she signed the deal with Unilever right before Christmas 2017.

Reflecting on her journey, she says, 'When I'm asked about what made Schmidt's so successful, I often say that my customers were my business plan. It started when I listened to those at the farmer's market, and it continued through each step of growth. Staying hyper-tuned-in to my customers always guided and served me.' Not sales. Not marketing. Customers, educating, and being educated.

Launch to Celebrate

A launch is a stepping-stone. A thing that happens when your business already has customers, is doing well, and is going to last. Many companies go out of business within the first year. Why make a big deal out of a business before you're sure it'll stick around? Instead, build a successful business and 'launch' as a celebration of your success. Spend your business's profits on it, not your own money.

Better yet, celebrate your customers' success. I think celebrating a milestone is a great excuse to launch. What about having successfully sold to a hundred customers? Once you're running a growing, profitable business with a hundred customers who love you and whom you care about, you can celebrate them-by launching. Throw a party. Invite all of your customers and thank them for their ongoing support.

Do that, and you'll have customers lining up at your door. They'll be people you already know, and who know you. Some of them will bring their own friends and families and maybe even members of their own communities too. They may even help promote your event before it happens because you've told them about it and they're excited about supporting you. Plus, they can actually speak to others about how great your product is and how much better it has made their life. Your customers may be even better salespeople than you are. Good-there's more of them than there are of you!

Or perhaps you decide you don't need to launch at all. That's fine too. But entrepreneurship can be lonely, and it can be a good excuse to rallyand reward-your community for helping you get this far.

Once you have a hundred customers, some of them now repeat customers, selling your product better than you can, you're ready to move on to the next chapter of your business: marketing.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Launches are alluring, but they are one-off events I wouldn't bet your business on. Instead, wait until you have a product with repeat, paying customers. Then launch by thanking them!

- Selling your product (or process) directly to customers may seem slow, but it is worthwhile. It will lead to a much better product because the sales process will be less about convincing and more about discovery.

- Start by selling to your family and friends before moving on to your communities and, finally, if at all, to total strangers. (The further away from you, the harder they will be to convince.)

Learn More

- Read Predictably Irrational , a book on human psychology and pricing, by Dan Ariely.

- Read How to Win Friends and Influence People , by Dale Carnegie, the best book I've ever read on 'sales.'

- Read about how important cold email-based sales were in Gumroad's early growth in this interview I did with Indie Hackers: www.indiehackers.com/interview/i-started-gumroad-as-a-weekendproject-and-now-it-s-making-350k-mo-4fc6cbc0e8.