build as little as possible

Make SOMETHING people want.

Y COMBINATOR

Make something PEOPLE want.

ME

The previous chapter was all about finding a problem worth solving for people worth solving it for. In this chapter, I explain how to develop your idea and how to figure out what you need to do now versus what can wait until you're in business. Knowledge is important, but so is momentum. You don't want to get so in the weeds on which programming language to learn that you never start making your dream app. Especially at the beginning, minimalist entrepreneurs have to stick to what is truly essential rather than try to learn and do everything all at once.

While writers are often told to 'write what you know,' for entrepreneurs the process isn't so simple. When you're starting a business, you're often imagining something-a product, a service, a business model-that's never been done before. That said, most successful minimalist entrepreneurs have a solid background (or interest) in one aspect of the business they're starting even if they don't know everything about it or exactly how to begin.

For me, it was designing pretty, accessible software. When the iPhone App Store launched in 2008, I was one of its first wave of developers. Not because I was determined to start a business, but because I was following my passions and curiosity.

Unfortunately, in my conversations with aspiring founders, this moment is when most folks decide that building a business is not for them. They have the passion, but they let self-doubt creep in, convincing themselves that they don't possess the hard skills they think they need, such as iOS programming or financial modeling. Let me tell you a secret. Every founder, even the most successful ones, knows nothing at the beginning, and learns from there. This is about interests, not skills. Instead of focusing on the things you do not know, focus on the things you do.

You do not need a team, money, or a degree to start building. You don't need to ship or to code to make your idea come to lifeat first . You might need them later, but when you are armed with a product that people truly value, these things will be easier and cheaper to acquire than you think. Often, they will find you. If your passion to solve a problem is genuine, you can overcome obstacles on your path one at a time. If you're on a mission to serve customers, you can learn what you need to know and delegate the rest. Just figure out where your skills, knowledge, and background intersect with the business you have in mind and leverage these strengths to the hilt. Don't get permission. Just get started.

Anna Gát, founder and CEO of Interintellect, was determined to build platforms where people could peacefully share their beliefs in spite of growing polarization in public intellectualand political spaces. The first inkling of the idea had come to her between Brexit and the 2016 elections in the United States. Gát felt that a great cultural shift was happening, and she was eager to be part of creating the way the world would look in the years to come. It was a bold idea, but she had accomplished a similarly challenging task several years before as cofounder of Hungary's leading women's rights website and events community, for which she won a Glamour Woman of the Year Award. Now she was focused on creating mediated spaces that would allow people with irreconcilable opinions to come together. Her first iteration was a platform for academics where adversarial conversation and research could take place, but within a few months, she found working with that community to be a much slower process than she had anticipated. What she was building wasn't scalable.

Her second version of the product, a messaging app that would facilitate public discourse through artificial intelligence, was even more ambitious. For two years, she poured all of her energy, money, and time into building a new platform, working nights and spending every dollar she had to fund testing and development. Unfortunately, as the product moved closer to launch, many people who had said they would use the app were not as interested as they had indicated in preliminary research.

'I was hell-bent on building technology,' she says, and the whole endeavor had been so expensive and time-consuming that she was reluctant to abandon it. But in the meantime, she was organizing in-person salons where people could share their opinions and ideas. She didn't consider these gatherings to be a business, but she knew she had inadvertently created the vibrant intellectual community she had been seeking-it was just happening through the salons rather than through the app.

Her entire career had been in tech, so building a company with zero tech felt counterintuitive. She abandoned the app anyway and pursued the 'grander' idea based on the energy and fun she felt in the salon community. Now Interintellect is growing sustainably and realizing her initial dreams by way of a low-tech, systematized solution that reflects what her customers want and need.

Later in this chapter we'll talk more about Interintellect, but I get why so many people start with software or technology when building a business. I love it too, but it's far too constricting at the beginning of the creative process. It makes the stakes too high, and it's too serious, expensive, and stressful! That doesn't mean you shouldn't use engineering strategies to get started. It's just that you don't have to jump straight into coding or programming to create the processes that will power your minimalist business.

The world will tell you to go big or go home, but I say go small at the beginning. And the smallest you could possibly start is to build nothing at all. Instead of skipping straight to software, stick with pen and paper.

Start with Process

Every big idea was small first. If you don't start small, if you can't help people one by one, you will struggle to build a business around your idea. Leave your ego at the door, set aside your concerns about funding and software, and focus on your first customers, using your time and your expertise to solve real problems for real people.

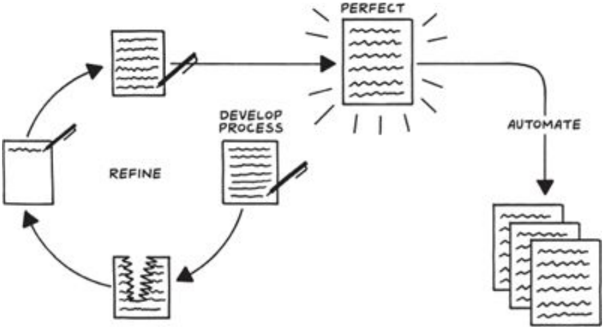

Now that people know you, trust you, and perhaps even turn to you for expertise, it is time to start helping them in a systematic, repeatable way that allows for continuous improvement and iteration. As you fulfill the first customer cycle, document each part of the process so that with every consecutive customer you have a playbook. This document will be the true MVP of your business. I'm not talking about the minimum viable product that we're all trying to build and to launch. I'm talking about the manual valuable process that precedes it and will be the foundation for the business you're trying to build.

Methodically creating this manual valuable process and recording the steps you take to complete it will help you figure out what's working and what isn't. It will also help you discover if you're making something that people actually need or will buy. In his book Anything You Want , CD Baby founder Derek Sivers writes, 'If you want to make a movie recommendation service, start by telling friends to call you for movie recommendations. When you find a movie your friends like, they buy you a drink. Keep track of what you recommended and how your friends liked it, and improve from there.'

Unfortunately, the English language does not have a word for this activity, so I made one up:

processize (verb)

to turn into a process:

After they tested it on their friends, they processized their recommendation system.

It really should be a word in the dictionary because it is so important on the path to building a business the right way. Unfortunately, many people miss this step, falter, and ultimately fail because they go straight from problem to product before learning exactly what and how to build. But processizing is a cheap, quick discovery process that is essential. 'Creating a product is a process of discovery, not mere implementation. Technology is applied science,' Naval Ravikant says.

Without processization, you may think you know what the customer actually wants, maybe even because the customer has told you what they want, and maybe even what they would pay for. But as Anna Gát can tell us, talk is cheap. Until you get through the entire process of solving the customer's problem and (ultimately) receiving payment, you won't know what the customer wants and is willing to pay for. You need to solve one customer's problem reasonably well, if imperfectly, before you can scale. If it works, great. If it doesn't, you may realize you want to scale up, but your customers couldn't care less. If that's the case, you may want to consider a different idea.

One minimalist business built on process is Endcrawl.com. For eight years, founder John 'Pliny' Eremic ran a post-production company for the film industry and watched filmmakers struggle to produce the end credits that listed all of the people, places, and organizations that appeared in or contributed to the making of a film. He and his cofounder, Alan Grow, knew there had to be a better way, and the obvious answer was some kind of software to manage the endless changes and updates that made the process so painful. But they didn't start there; instead, they set up a Google Sheet and a simple Perl script to build end credits to help them learn about their customers and validate some of their core assumptions. Their initial process looked like this:

- First, they gave customers a Google Sheet with their end credits formatted to their specifications.

- Customers could edit the Google Sheet as often and as much as they like.

- Once customers wanted a new 'render' or video output of the credits, they emailed the request.

- Pliny or Alan manually exported their Google Sheet to CSV.

- Then they manually ran the CSV through the Perl script.

- Next, they manually uploaded the files to Dropbox.

- Finally, they manually emailed the customer the download link.

For filmmakers used to waiting up to twenty-four hours, it was a revelation that this process, even manually, took only about fifteen minutes. It also allowed the customers to control their data and to do an unlimited number of revisions for a fixed price until the credits were just right. For customers, life was just a little bit better. For Pliny and Alan, it was a chance for discovery.

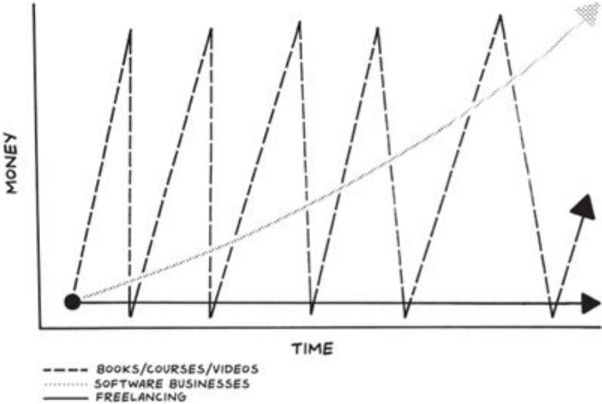

Build Last

Even after you help your first few customers, you might not be totally sure how to solve the problem you have chosen to solve for your community, but one of the easiest ways to get started and to experiment is to freelance. Selling your time does not scale nearly as well as other types of businesses but can generate positive cash flow much sooner, giving you the breathing room to think about what comes next.

In my experience, many of the best minimalist businesses started out as freelance work or side projects before evolving into viable companies with potential for long-term growth. As you consider what exactly to build, there are a few routes that will get you to a profitable, sustainable business in the quickest, most efficient way. They are:

Forms of self-employment income for developers

- Selling your knowledge and teaching people via digital content (videos, ebooks, podcasts, and courses). Lynda.com, which LinkedIn acquired in 2015, grew from a book and a series of in-person workshops led by Lynda Weinman. When the dot-com bubble burst in 2001, Lynda and her husband, Bruce Heavin, offered a subscription service to the online educational videos they made about web design, an idea that was new at the time. At first it seemed that the business would not survive, but as Lynda.com's subscribers grew from just a few hundred to hundreds of thousands, their industry impact also expanded astronomically.

- Selling a physical product (merchandise or a unique product offering). Noxgear manufactures light-up visibility vests for runners and cyclists. The idea first came to cofounders Tom Walters and Simon Curran when they patched together a version of what would eventually become the Tracer360 for their nighttime ultimate Frisbee games. When they looked into what was available in the marketplace for earlymorning and late-night athletes, they saw an opportunity, prototyped their product, and sold the first five hundred vests on Kickstarter. They've since added the Lighthound, a light-up harness for dogs.

- Connecting people for a flat or percentage fee. Craig Newmark started Craigslist as an email list among his friends, highlighting local events in the San Francisco Bay Area worth checking out. Today, they are doing over $1 billion in revenue per year, with fewer than a hundred employees. But while Craigslist is the quintessential example of connecting people, there are many ways to do this. Job boards, like People First Jobs (which we discuss in chapter 7 on culture and hiring), connect companies with candidates, often charging a flat fee for doing so. And there are communities too, like Product Manager HQ, that connect like-minded folks with each other.

- Software as a service (SaaS). The idea of building a software solution that would optimize remote work and minimize distractions came to Justin Mitchell and his team at Yac in 2018. In four days, they built the first iteration of what would eventually become their asynchronous voice messaging app for Product Hunt's Makers Festival, because they saw a hole in the market for remote workers who were constantly dealing with the demands of Zoom meetings and the distraction of Slack. Although YAC's platform, integrations, and features have grown since then, it all began with the small idea of eliminating interruptions.

In the last chapter we covered the four different kinds of economic utility: place, form, time and possession. To come up with your offering, you'll likely overlay that list onto the list above to come up with the type of business that best solves the problem you're trying to solve for your customers. For example, you may save people time (time utility) learning a new skill with an online, cohort-based course (digital content). Or you may build software (form utility) that automates a manual, physical process (SaaS).

Over time, your business will likely offer two or more of these products and services, but at first, you should pick one to focus on and get started. In general, that should be the one that lets you begin today, instead of tomorrow.

Remember that you don't have to know everything about what you're doing at the beginning (or ever), and many people are wrong the first time about what they are building. The fact is, it's very likely that you discover the kind of business you should be building as you are building another business you thought you should be building. As Adam Wathan of Tailwind UI says, 'Want to find a good SaaS idea? Start a business, literally any business. You will soon realize how bad every existing tool is that you have to pay for to run that business, and you will quickly become overwhelmed by the number of things you feel you need to build yourself.'

If you make a false start, just go back, reset, and begin again. Nothing you've done or learned is ever wasted. A sustainable, growing business will take years to fully develop, and because you are growing as the business wishes you to, you have the time to make adjustments and learn the skills you need to know to succeed at each step. That's because you are not doing this the unicorn way, which the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen refers to as 'baking a cake in three minutes.' You are using your slow cooker to make a soup, on low heat and in full view.

And if you're not rushing, you have time to talk to customers, time to iterate, and time to test your hypothesis.

Test Your Hypothesis

A business hypothesis is just like the one you learned in fifth-grade science class. It is a suggested solution for a problem that does not currently have a solution. It must be testable (able to be tested repeatedly and independently) and falsifiable (able to be proved wrong).

For example: My customers will pay a fixed fee with a small premium to get their end credits quickly and efficiently produced with as many renders as they need .

Every business starts by testing a hypothesis with real customers. And if you only have one customer, you can treat your startup like a white-glove service. This may mean a phone call or sitting across the table from your customer at a local coffee shop, helping them with their problem.

The goal of these meetings is to validate this hypothesis. It takes time to test and honest reflection to recognize when you are wrong. But it is better to be wrong now, when the stakes are low, than to be wrong after you have spent five years and some of your own personal capital trying to build your idea into a business that was never meant to exist.

When you are validating a hypothesis, do not ask leading questionsquestions that point people to the answer you want to hear. Instead, think about creating the kind of feedback loop that author and tech entrepreneur Rob Fitzpatrick writes about in The Mom Test . When you ask the kind of questions he recommends, the kind even your mom can't lie to you about, you will get the honest truth, because no one will know that you have a new idea for a business and that you're testing to see if it's viable. For example, you shouldn't ask:

Would you pay for my product?

Instead, ask:

Why haven't you been able to fix this already?

There are many businesses that cannot be proved in this way, but these are not the types of businesses we are interested in building. We're aiming to build businesses that are testable at a small scale, and can then be scaled up gradually, over time.

Another benefit of this approach: You can charge for it. If you are genuinely helping someone, you do not need to wait until you have a product to sell in order to make money. You can be paid for your time like Pliny and Alan were even before they technically had a 'product.'

In their case, the process they created proved their hypothesis that filmmakers would pay for a solution to the problem of trying to finish the credits. Your first idea may not go as smoothly, and that is totally okaymost experiments are wrong. You are at the frontier, literally trying to make something that does not exist yet, and you will be wrong a lot on the way to

And when you do arrive there, you will have a document that dictates your perfect process, because as you've walked someone through solving their problem, you've refined the steps it takes to get there. This process will take future customers from nothing to something. It's something you can share (perhaps publish). You haven't made any money. You don't necessarily have a business yet . But you've provided what Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator among many other endeavors, calls a 'quantum of utility: when there is at least some set of users who would be excited to hear about it, because they can now do something they couldn't do before.' figuring out what your customers want. As long as you are working toward being right through processization, you only have to be right once.

Do One Thing Well

Before I launched into research or coding or brand building, I picked a single problem to solve for myself and for my community of creators: selling digital files to their audiences. The basic assumption was simple, that people were starting their careers on the internet, some of them finding enormous success through social media rather than with websites and blogs. But at the end of the day, when they needed a platform to sell what they were making, they still wanted somewhere to send people and a streamlined way to deliver digital files and get paid for them.

At its start, like any good product, Gumroad really only did one thing. The original Gumroad website reads:

-

- Take a file or a link of value. This can be anything. From a link to an exclusive build of an app, to a secret blog post, to an icon you spent hours designing.

-

- Share it. Just like any old link. Choose your own price. You don't have to create a store. And you don't have to do any management.

-

- Make money. And that's it. At the end of each month we'll deposit the money you've earned to your PayPal account.

If you think building an app like that is insanely complicated, it may be useful to know that most apps on the internet consist of two things: forms and lists. Twitter, for example, has a form you use to tweet (with a single input) and a list of tweets you see from people you follow.

These apps are referred to as CRUD apps, as they have four actions you can take: Create, Read, Update, and Delete. And Twitter doesn't even let you edit tweets!

Gumroad fit this model. At first, I let a creator create, edit, and delete products, and allowed consumers to view them ('read' them). Stripe made payments easy to take, and Pay-Pal made it easy for payouts to be sent out (albeit manually at first).

Gumroad didn't have file uploading at the time (you had to specify a destination URL post-purchase, like a YouTube URL), and I didn't even have automated payouts or fee calculations. That was all manual.

The whole app was twenty-seven hundred lines of mostly copy-pasted code in a single Python file, hosted on Google's cloud. (I've since opensourced the code; find the link at the end of the chapter.) But it worked! It solved the problem. So I launched. Of course, it wasn't 'ready' for the masses, but ten years later, Gumroad still doesn't feel ready. I don't think it ever will be.

Wait a second, no payouts? Nope! Instead, I collected everyone's PayPal information. At the end of every month, I made a list of everyone's email addresses and their account balances, and paid everyone out one by one. Eventually, I started to automate bits of it. Instead of copy-pasting lines from the database, I wrote some code to download a list. Later, I wrote a script that would issue the payouts using Pay-Pal's API.

There were still issues. For example, whether you made a sale on August 1 or August 30, you would still be paid out on August 31, meaning fraudsters could make a bunch of sales a few minutes right before they're meant to be paid out, circumventing our ability to review and block the transactions. Since then we've added a seven-day buffer, though we got away with not having any buffer for at least a year or two.

Over time, we automated absolutely everything, which made all the difference when I needed to run the ship single-handedly. But we didn't start there! First, I 'hired' myself to do it. Then I built a process around it. Then we turned parts of it into a product, now wholly automated.

What Should I Build?

To this day, processizing is a concept we employ over and over again at Gumroad. Everything I do is listed on a piece of paper that everyone in the company can access. When I go on vacation, someone else can take over my job. And if I get hit by a bus, the company doesn't go under. Once you have this magic piece of paper, you can turn your process into a product. We don't have to make up a new word for this because it already exists: 'productizing.'

Productizing simply means developing a process into something you can sell. In the processizing stage, you created a manual valuable process for yourself and built a system for working efficiently and effectively as you helped each individual customer. Now you are ready to productize, which means that you automate each individual task so that people can sign up, use, and pay for your product without you being involved.

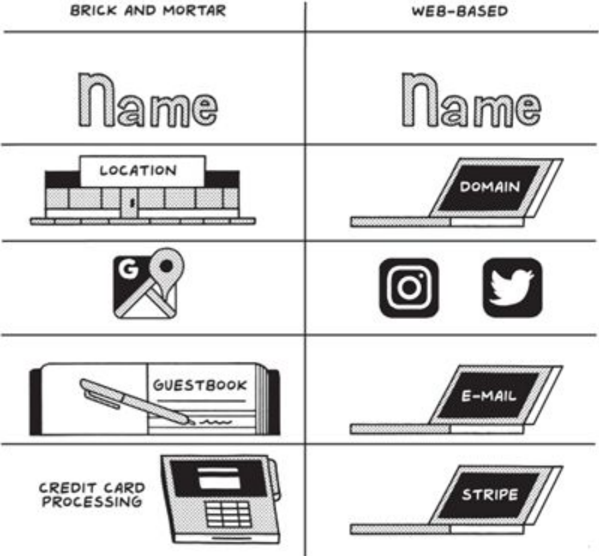

If processizing is how you scale a manual process, then productizing is how you go fully automatic. Just like a brickand-mortar business in your local community needs some essentials to get up and running, you will need to do the same for your minimalist business. And if you have to go back a few steps, don't worry, because that's part of the process too.

- Name your business. Before you can tell anyone about your product, you need a name. I like names that take two words and combine them, because I find them easier to remember than a new, made-up word. I also think they help with word of mouth because everyone will know how to spell them. This is also called a 'radio test': If someone hears your business's name on the radio, can they find it using Google? Gumroad, Dropbox, and Facebook follow this model. But honestly, your name doesn't matter much. Take it from the founder of Gumroad. If you're successful, your name will feel right.

- Build a website and create an email address. The equivalent of your brick-and-mortar store is a website. To do that, you need to buy a domain; it will cost you about $10 (renewing yearly). Connect it to a website-building platform like Carrd, Gumroad, Wix, or something else. These will cost about $10 a month. Create an email address for yourself

with that domain (sahil@gumroad.com, for example), as well as a password manager.

- Create social media accounts. You'll need two sets of accounts, one for you personally and one for your business (you'll see why in the chapter on marketing).

- Make it easy for customers to pay. Get a Square or Stripe account. These are payment processors that will help you collect credit card payments online and in person. They are free to sign up for and cost about 2.9 percent plus 30 cents per transaction. (You may want to spin up an LLC too, but I tend to wait until I have a few customers before committing.)

Now your business is ready to accept your first customer. If someone asks you what you are working on, you can give them a URL they can check out (if not checkout!). At the beginning, you should use it to explain what your product does and provide an email for folks who may be interested in such a thing, even if you do not have a product yet. You can and should always be learning and interacting with prospective customers.

Once you have these in place, you can start building. But what exactly to build? As little as you can. We'll get into launching in the next chapter, but this chapter is about building. That means you need to start shipping, and shipping means you should start with almost nothing, because the job is to start delivering value for your community/customers as quickly as possible. And they don't want to wait!

Constraints Lead to Creativity

If you're a minimalist entrepreneur, the early stages are all about constraints. Now that you're productizing, you have to add in more limits. In addition to your product doing just one thing (at first), there are other ways to control the temptation to try to do everything at once . . . or to try to do it perfectly.

I ask myself four questions every time I want to build something new:

-

- Can I ship it in a weekend? The first iteration of most solutions can and should be prototyped in two to three days.

-

- Is it making my customers lives a little better?

-

- Is a customer willing to pay me for it? It's important for the business to be profitable from day one, so creating something valuable enough for people to pay for is key.

-

- Can I get feedback quickly? Make sure that you're building a product for people who can let you know if you're doing a good job or not. The faster you get feedback, the faster you'll build something truly valuable and worth paying for.

Note that there are no constraints around how pretty the product is or how well written the code is. That's another reason to do as little as you possibly can: to be honest with yourself about how useful your product actually is. A product that is beautiful or has great marketing behind it may feel more useful than it actually is . But if your product is incredibly minimal and useful, and people look past the lack of polish and use it, you will know you are on to something.

The perfect example of this is Craigslist. It's never been pretty, but it's always worked so well that it didn't matter. And it's so useful that it's spawned a whole world of businesses created from that model. The goal here is to build something 'good enough.' Good enough to show others, and good enough for them to pay for. Which is almost always much less than you think.

Ryan Hoover launched Product Hunt, a site for product-loving enthusiasts to share and geek out over the latest mobile apps, websites, hardware projects, and tech creations, with an email list and Linkydink, a tool for creating collaborative daily email digests. It happened quickly. Hoover says, 'Over Thanksgiving break, we designed and built Product Hunt. . . . [Five] days later, we had a very minimal but fully functional product. We emailed our supporters a link to Product Hunt, informing them not to share it publicly. The supporters were thrilled to join and play with a working version of something they had thought about and, indirectly, helped build. That day we acquired our first 30 users. By the end of the week, we had 100 users and felt ready to share Product Hunt with the world.'

From the very beginning, Product Hunt had enough momentum that Hoover realized it was a project worth pursuing. His day job building tools for game developers had given him time and space to experiment (see freelancing), and he had a clear idea of what he wanted Product Hunt to be. He knew he didn't need to reinvent the wheel; he could use something similar to the format of Reddit. But since he wasn't an engineer, he still found himself asking, 'How am I going to build it? Who will develop it?' In the end, rather than get bogged down by those questions, he decided that the newsletter was a superquick, no-code way to get the project off the ground and build some confidence around his idea.

Like me, Ryan doesn't believe that founders should start with code. 'Do shitty work people love at first,' he says. As more and more infrastructure gets built by new businesses (including, perhaps, the one you're working on now), it is getting cheaper, faster, and more accessible to build an MVP without code. What that means is that you shouldn't wait until tomorrow to get started. The lower the barriers to entry, the more competition you will have.

The trendline is simple: democratization. Everything that a software engineer can do today, everyone can do tomorrow. It means you need to know less to do more. Even if your service is manual, or your product is physical, you will be able to take advantage of software to provide your service as efficiently as possible. Every single business is in some way techenabled, even though the end product may not be.

For example, if you are building a software business, you can visit Makerpad.co and learn how to connect Gumroad and Carrd to accept orders on your website without writing a single line of code. And when you are ready to automate your manual fulfillment process, it will teach you how to add Airtable and Google Forms and Mailchimp. There are products like Notion, which we use to run our entire company. And there are services like Zapier, which allow you to automate the connections between all the software you use. Seriously, check out Makerpad. You'll be surprised how much you can build without writing a single line of code.

Similar to processizing your workflow as you were helping people, these tools will let you processize and later productize the internal functions of your business itself.

Perhaps most important, they will save you money. The further you can get without hiring your first engineer if you are building a software product, the higher your chances of achieving profitability. And the further you get, the better the employee you can hire. (And more often than you think, these people will find you!)

Ship Early and Often

Building a business is a lesson in fast feedback loops and iteration. Imagine if you were on a boat searching for treasure, but you could only ping your radar once a year. Then once a month. Then every day. The boat is your business, and the treasure is product-market fit.

You will be wrong a lot; the goal is to get less wrong as quickly as you can. This is why shipping early and often is so important. Gumroad, for example, has never shipped a 'v2' in ten years. Instead, we have shipped tens of thousands (literally) of incremental and major improvements over time. Each time, we cross the threshold for some customer from 'I may want this later' to 'I need this now.'

Your goal is to move away from being paid directly for your time. This is important because your time is far more valuable than your money, and so you should almost always welcome the trade. Over time, you can improve on the exchange rate, but you should always know what it is.

For example, if you are helping people for $10 an hour, you can set a goal to get to $20 an hour. You can do this by building software tools to help you do your job twice as fast, or you can increase demand for your service such that you are able to charge more. Ultimately, you will be able to make the equivalent of thousands of dollars per hour, but at the beginning you're still learning and iterating as fast as you can. After all, what matters is not just the processes you build for your business; it's also the processes you build for yourself.

While it may seem obvious how to productize a SaaS business, productizing isn't just about coding and software. It applies to any minimalist business, including Interintellect. Because Anna Gát processized early, Interintellect has a predictable, repeatable format based on four pillars: creating a moderated space, allowing equal speaking time for participants, promoting fun and entertainment, and establishing a patient, transparent, multidisciplinary atmosphere. The salons are organized and tracked by topic, time zone, and host, and a tight feedback loop allows the company to surface the most discussed topics in the community forum and to program events based on customer preferences.

'One interesting thing you only learn in practice after doing it a thousand times,' she says, 'is what you're really making. I was convinced I was making events at the start, but I'm really making hosts.' As a result, Gát has launched a new platform that will enable hosts to build and schedule their own events and to approve, onboard, and train new hosts based on the incredibly strong set of norms by which the community abides.

As Interintellect expands, Anna expects to further automate the company's processes so that they can host sixty events per day around the world. For her, the goal of Interintellect salons is ultimately entertainment even as she systematizes a ritual around how people congregate so that they can learn, share, and interact in an intellectually relaxed space. Even if your business doesn't at first seem to lend itself to processizing and productizing, Interintellect is a good example of how this methodology can be applied in almost any setting.

Create Conditions for Liftoff

At the end of the last chapter, I talked about squashing doubts, but if you're like 99 percent of the founders out there, doubts will be with you every step of the way, especially when you bring your product out to a community that you know and respect. Even though selling to strangers is inefficient, people are still desperate to avoid the awkwardness of telling their community what they're working on. Sorry, but it's still absolutely critical to start there.

This self-doubt never goes away. Even when you conquer community, you'll still have self-doubt about product. When you build and ship a product, you'll have self-doubt about sales. When you've done everything mentioned in this book, you'll have self-doubt about whether you're qualified enough to write it all down. (Hi!)

Just get going, and keep going. Your failures will fade, while your successes will stick around and compound. You didn't believe you'd get this far, yet the data shows that you did. Remind yourself of that as often as you need to, I certainly do.

We began this chapter talking about momentum. Let's finish talking about confidence: As you build the solution you'll sell to your first customer, you will also gain the confidence to know you're on the right track and take the next leap forward.

If you're lucky, you may be able to get away with building almost nothing. If you've solved a true pain point for real people, they won't fault the simplicity of your offering but appreciate you for it. Some will even ask to pay. This is the exciting part: You made your first dollar on the internet. You crossed the great divide from zero to one. You started.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Refine a manual valuable process before building a minimum viable product.

- The faster the feedback loop you have with your customers, the faster you'll get to a solution they will pay for. The fastest feedback loop will be one you have with yourself.

- Before you build anything at all, see how little you can get away with charging for it. Even later, build only the things you need to build. Outsource the rest.

- I define 'product-market fit' as having repeat customers who sign up and use your product on their own so that you can start to focus on outbound sales.

Learn More

- Read Getting Real , a free 'book' about building a web app, by Basecamp, available online at https://basecamp.com/books/getting-real.

- Read The Mom Test , a book on how to talk-and listen-to customers, by Rob Fitzpatrick.

- Browse Gumroad's original source code, which I recently published online at https://github.com/gumroad/gumroad-v1.

- Explore Rosieland, @rosie.land, a resource for community builders created by Rosie Sherry.

- Follow Daniel Vassallo (@dvassallo) on Twitter. He made a living on Gumroad before joining as our quarter-time head of product.