start with community

It takes a village to raise a child.

AFRICAN PROVERB

In 2009, Sol Orwell was overweight and unhappy, so he decided to join the 'r/Fitness' subreddit, one of the thousands of smaller online communities within Reddit, to find information and support. At the same time, he started reading about fitness and nutrition, taking notes on what he was learning in books like Tim Ferriss's The 4-Hour Body and posting summaries on the fitness subreddit for other members of the community. Reddit was a natural place for Orwell to seek connection. He was already participating in the NBA and Toronto subreddits, among others, so he knew and understood Reddit's rules and norms about posting only authentic, useful content.

The more he learned about fitness and nutrition, the more he shared. In addition to his reading notes, he inspired others by answering questions and documenting his personal journey of losing sixty pounds, which occurred over a period of several years. He credits his physical transformation to the relationships he formed with other 'redditors,' including Kurtis Frank, one of the moderators of r/Fitness. Eventually, Sol and Kurtis ended up moderating the subreddit together, and as time went by, they noticed two persistent problems.

First, little reliable information was available about nutritional supplements, either from other redditors or from the companies that made these products; second, almost every day, new members asked the same questions over and over again, many times about supplements. Sol was frustrated by both situations, but eventually he realized that maybe the resources people needed just weren't out there.

Sol and Kurtis saw a job to be done for a community that they cared about and had nurtured from five thousand to about fifty thousand during the two years they had been moderating. In 2011, they launched Examine.com, a website where people could find the kind of free, unbiased, up-to-date research and information on nutrition and supplements that they themselves had been looking for.

They told people about their project, but they didn't sell anything, and they only occasionally dropped links in the fitness subreddit when they were answering questions. Instead, other members of the community did it for them. After all, they had been part of Reddit at this point for about five years. Sol remembers they both had something like '100,000 plus karma,' a measure of how much a user has contributed to Reddit based on upvotes and comments from other users- so people trusted them, and they were solving a problem for the fitness subreddit without asking for anything in return.

In 2013, two years after they started the site, they started to think about monetizing, so they surveyed the community about what problems they believed the information on Examine.com might be able to solve. 'We would ask people, 'What's your problem? What do you wish you could do?'' Sol remembers. 'The most common thing was 'We wish you just had a table of all of the information you have. So if I wanted to look at supplements that affect blood pressure, I could look it up quickly.' ' Because of those answers, they offered their first product, the Research Digest , a comprehensive guide to supplements and nutrition.

Sol was well known in the health and nutrition space, and to promote the Research Digest, he leveraged his relationships with fitness professionals four years after initially joining the fitness subreddit. When he and Kurtis launched, 105 people in the fitness industry shared the link. The goal was a thousand sales, and by the end of the first day they had already sold six to eight hundred copies. By the end of the launch, they had sold three thousand copies, all based on reputation, trust, and word of mouth.

Fast-forward to today, and Sol is happy, healthy, and wealthy. Examine.com continues to be an important resource for health and nutrition professionals; it has seventy thousand visitors per day and does seven figures in annual revenue, though Sol has since stepped back from the dayto-day operations. The team has expanded Examine's offerings to include additional guides and subscription services on how supplements factor not only into fitness but also into longevity, chronic disease, and psychological health. But they've never lost their focus on community and continue to depend on the trust and relationships that grew authentically over time.

In this chapter, we'll talk about how you can find your own communities (if you haven't already) and how to uncover the kinds of problems that might be best suited for a minimalist business. I won't lie. This process takes time, but done right and, most of all, done authentically, it will be the basis of how you move forward now and for years to come. Whether you're just getting started or you're already in the process of building a product, knowing and contributing to your community is key at every stage. Remember that, and you'll find and nurture the right atmosphere for collaboration, growth, and eventually a sustainable business that matters.

Community First

Community is a fundamental societal unit. From Sol's r/Fitness subreddit to yoga classes to family to the group of friends we game with in the middle of the night, communities are a place where we can connect, learn, and have fun. For minimalist entrepreneurs, communities are the starting point of any successful enterprise.

That doesn't mean you should run out and find a community to join just for the purpose of starting a business. It means that most businesses fail because they aren't built with a particular group of people in mind. Often, the ones that succeed do so because they're focused on a community that a founder knows well. That process can't be rushed because it comes from authentic relationships and a willingness to serve, both of which take time to uncover and develop. You may even have to learn a new language-or at least some insider lingo.

Communities used to be limited by geography, but it's never been easier to connect to people with whom you share something in common, whether it be an interest, a favorite artist, or a belief system. But a community isn't a group of people who all think, act, look, or behave the same. That's a cult.

A community is the opposite. That's what I discovered when I moved from San Francisco to Provo and got out of the Silicon Valley bubble. For one of the first times in my life, I saw that the best communities are made up of individuals who might be otherwise dissimilar but who have shared interests, values, and abilities. It's a group of people who would likely never hang out with each other in any other situational context, and it often encompasses virtually every identity, including, yes, politics.

A community can override people's dislike of one another. Every Sunday in the Latter-day Saints Church, I saw the progressive next to the conservative, the rich next to the poor, the young next to the old. I'm not sure what they thought of each other outside the church building, but for at least one day a week, they sat together for the sake of the community.

It wasn't easy. It was real work to be an active participant in that church community, to learn how to speak the language, but for the first time in a long time, I was reminded of something important: you don't have to bring your whole self to every community you join, but you do have to bring a slice of yourself. And that part needs to be authentic to its core. It's the combination of time and vulnerability that leads to relationships and growth.

Part of my own growth was realizing that as an outsider, I was in a particularly great position to see the community with fresh eyes and to contribute value in a new way. You may never move to a new city, but getting out of your bubble matters when it comes to community. And it's healthy and normal to leave certain communities as you explore new ones.

You don't have to bring your whole self to every community you join, but you do have to bring a slice of yourself.

For me, my move from Silicon Valley to the Silicon Slopes showed me that I didn't care too much about tech, at least not in the way that I thought I did. In Utah, I didn't go to Java-Script meetups or attend design lectures or judge startup pitch competitions. Instead, I found myself at figure drawing classes. Or a few hundred feet away from a barn, learning how to plein-air paint. Or at a coffee shop on Thursday mornings, writing and reviewing science-fiction stories with a few friends I met at a workshop.

Finding these creative communities in real life reminded me of the spark that inspired me in the early days. And rediscovering myself as a creator and spending time with other makers reconnected me to why I had built Gumroad in the first place: I loved to create! I couldn't believe I had forgotten that, for years.

I was accidentally at the forefront of a movement that was taking shape -what Li Jin, former partner at Andreessen Horowitz and founder of Atelier Ventures, calls the 'passion economy'-'a world in which people are able to do what they love for a living and to have a more fulfilling and purposeful life.' At the time I created Gumroad, online creator platforms were still new, but the rise of no-code solutions has made building and charging for podcasts, video and audio content, online courses, virtual teaching, and virtual coaching almost seamless, so that starting a business around something you love has never been more attainable.

You probably have something you enjoy, something that on its face has nothing to do with your 'real' job. Maybe it's marathon running or ceramics or electronic music or another passion that you pursue in your free time. Whatever it is, building a minimalist business around the people you love to spend time with and the ways you love to spend your time depends on being part of a community. You may already be thinking about how to solve the problems of a current community you participate in, or you may simply be planning to join a community based on something you love. Either way, finding your people is really important at the beginning. Not just for the sake of your business but also for the sake of your own wellbeing.

Taking writing and painting classes in Provo reminded me that my community wasn't just the people in front of me; it was also a wider group who wanted, like me, to 'turn their passions into livelihoods.' The real communities I was a part of didn't care about growth at all costs; that kind of accelerated expansion would have cracked them into a million little pieces. Instead, their priority, like mine, was connecting to each other in ways that allowed for the space, time, and freedom to explore their interests and to eventually transform their passions into businesses in meaningful ways.

Find Your People

Many people struggle to consciously place themselves within communities, even though everyone is already a part of several. If you're reading this and wondering which communities you're already a part of, ask yourself these questions:

If I talk, who listens? Where and with whom do I already spend my time, online and offline?

In what situations am I most authentically myself? Who do I hang out with, even though I don't really like them, but it's worth it since we share something more important in common?

Spend an hour, at least. Let yourself think you've run out of ideas at least a few times. In the list you end up creating, you'll find the people you are meant to serve. You may be tempted to skip this exercise if you've already started a business, but I believe that doing this regularly is a good opportunity to remind yourself why you're doing what you're doing and, most important, who you're doing it for.

From here, you can turn your list of communities into a list of locations -geographic and online-in which to spend even more time learning and contributing:

- For every group with a shared interest, there's a Facebook group, a Reddit community, a Twitter or Instagram hashtag, or some other form of gathering and sharing ideas on the web. There are often several. Join them all.

- There are communities run by the businesses that service that community: forums, groups, and more. Join those too.

- There are also notable teachers, with online classes that also function as communities. They may be also worth joining- though be mindful of the cost.

- Of course, there are the in-person communities! There are meetups, workshops, classes, speaker series, networking events, and more.

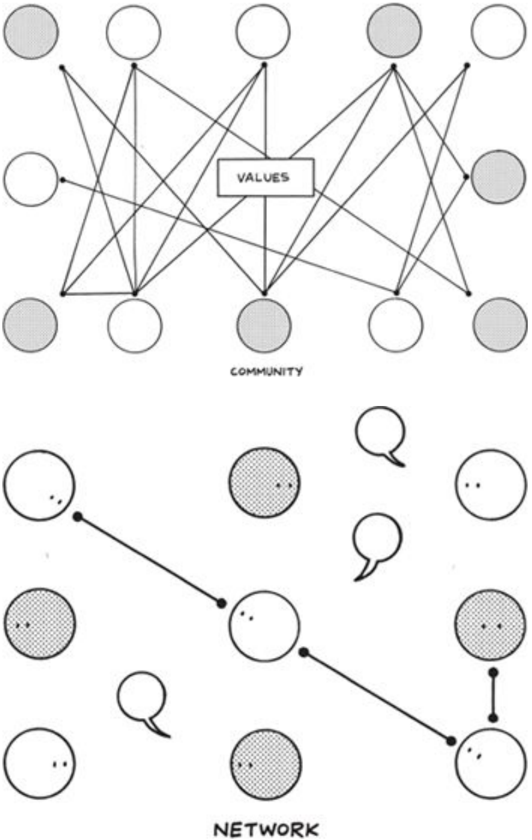

It's important to note that your goal here is to join communities , not networks.

In a network, such as Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, new-comers start at zero. No one says 'hi' when they walk in the door, and if you have something to say, there's no guarantee that anyone will hear or help.

Networks, in person or online, aren't bad. Sometimes they can lead to genuine and meaningful connection, especially over time, as you gain friends and followers and the algorithms start to recommend your work and your content to people who don't already know you. But where did those friends and followers come from in the first place? The communities you're in! (Note: Networks and audience are really important for the minimalist entrepreneur, just not yet. We'll cover them deeply in chapter 5.)

Eventually, you will be part of various networks as the face of your business, but at the beginning, beware of believing that communities and networks are interchangeable, no matter how appealing the potential virality may seem. Instead, build deep relationships first.

Contribute, Create, and Teach

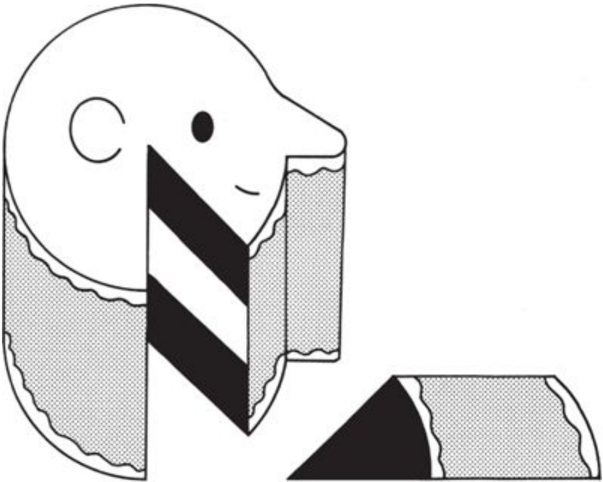

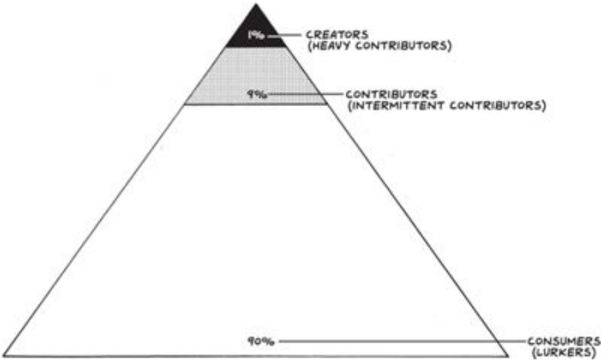

Being a member of a community is a start, but the real magic happens when you start to contribute. Authors and bloggers Ben McConnell and Jackie Huba call this the '1% Rule': On the internet, they say, 1 percent create, 9 percent contribute, and 90 percent consume. They've shown this rule to be true when applied to sites like Wikipedia and Yahoo, and it's also widely applicable to other collaborative websites. For example, most people do not post, comment, or even upvote on Reddit like Sol Orwell and Kurtis Frank did. Instead they browse anonymously, which is known as 'lurking.' To cite one example, even when the r/Askreddit subreddit was getting 1.5 million unique visitors a day, it was only getting 2,674 submissions and 110,408 comments in the same period.

If you contribute, you will have ten times the presence of someone who doesn't. And it will continue to grow from there.

Contributing means commenting, editing, and generally being part of the broader conversation. What's more, if you go further and create by showing what you're working on, teaching what you're learning, and bringing new material to your community, that influence will grow ninetyfold. Of course I am simplifying, but hopefully the point stands: While it's better to lurk rather than needlessly comment, it's even better to add value into the community even if you don't feel that you're ready . If you struggle with this, as many do, remind yourself that if you have something to add, it's selfish to keep it to yourself!

Once you begin contributing, folks will start recognizing your name. Eventually, some may seek your words of wisdom by '@mention'ing you directly or by following you so they get notified every time you post.

When I lived in Utah, I met several painters who built communities and eventually businesses in this way. One example is landscape oil painter Bryan Mark Taylor, who was part of a community of painters and art enthusiasts participating in and attending plein-air painting competitions up and down the California coastline. He sold his work through these competitions and established a loyal group of collectors and fellow artists, who followed him to Instagram. There he grew his community by posting more of his work and educational videos. When his easel broke on a backpacking trip in the early 2010s, he created the first prototype of the Strada Easel to solve his own problem. And because his community had grown organically over a period of years and through a shared passion, he had thousands of other painters he could share it with who then wanted one for themselves. Today, the Strada Easel makes him and his employees a happy living, and he gets to paint as much as he wants.

Once you're regularly cultivating relationships by contributing to the conversation, the time will come when you're ready to go further and educate others. But what will you say and how will you engage the people you've come to know and respect in your community? It's all about creating value and can all be summed up by three signs Nathan Barry, the founder of ConvertKit, which provides email marketing for creators, has hanging in his office. They read:

- 'Work in Public'

- 'Teach Everything You Know'

- 'Create Every Day'

If you're always learning, you'll always have something to teach others about their own next best steps.

When Nathan started blogging and publishing ebooks in 2006, he struggled to grow the community for his work, while others in his space seemed to have no trouble at all. One web designer he followed was Chris Coyier, who was regularly posting articles and tutorials on his website, CSS-Tricks.com.

Chris had a following based on his articles, and in 2012 when he needed $3, 500 for living expenses to take a month off to redesign his site, he promised recorded tutorials about the redesign process in exchange for a contribution to his Kick-starter campaign. In short order, Chris raised $87,000. 'I couldn't help but think how Chris and I had equal skill sets when it came to web design,' Nathan writes. 'We started at the same time and progressed at the same rate. So how did Chris have the ability to flip the switch and make $87,000 off a Kickstarter campaign and I didn't have the ability at all? What was the difference?'

They were both doing the work, but Chris was sharing it, while Nathan was not. 'I realized I would take on a project, do the work, deliver the project and move on,' he said. 'Chris did the same thing, BUT before he moved on, he would teach about everything he learned doing that project. When he could, he shared samples, he wrote tutorials about the code he wrote and any specific methods he went through. He did this with every project. The difference was that all along the way, Chris was teaching everything he knew and I wasn't.' Since that epiphany, ConvertKit has grown to over $20 million in annual recurring revenue.

Chances are, if you've learned something, there's probably a good portion of your community that would find value in learning that same thing from you, even if you aren't the world's leading authority on the subject.

And if you're regularly learning, then you'll always have regular content to contribute to the community. This can become a nice flywheel over time, as teaching often becomes the best way to drive your own curiosity and inspiration to learn more yourself. And when you learn publicly, your students will have questions that force you to learn even more stuff to teach them.

You don't have to teach everything you learn. In fact, a narrower core focus can be better. For example, Patrick Mc-Kenzie, a writer, entrepreneur, and software business expert who is best known for a 2012 post on salary negotiation that has since become a cult classic in the software engineering space, believes that the best personal brands exist at the intersection of two topics. He now works for Stripe, where he continues to write and advise software engineers and software entrepreneurs about how to start and scale their businesses, speaking from real experience as a creator and business owner himself.

If you're learning every day, which you probably are, you'll have something to share every day. Meanwhile, you'll build your skills and experience, learn to speak the language, and grow your community, all essential ingredients when you eventually have a product you are ready to sell.

Unfortunately, as you probably already know, there are no shortcuts. As you think about what you're creating now and how that might lead to a business in the future, look to the communities you're already a part of. You've invested time and energy there, so perhaps you already have an idea of how to proceed. If you don't, keep going, and continue using your time to get strong, to learn how to paint, to learn how to code, to learn how to write, or to learn whatever else you are into, teaching what you're learning along the way.

When you are proficient enough to monetize what you know, now or in the future, if you've put in the time, you will be part of a sizable community that will eventually be your first group of prospective customers (more on that in chapters 4 and 5). This is an important factor in keeping you honest about the quality of work you are able to produce. Your community should serve as proof that you're improving, producing, and helping others; these people could spend their attention on a gazillion things, and they've chosen you.

Becoming a person who helps people precedes building a business that helps people. It's not a coincidence. When you become a pillar in a community, you gain exposure to the problems that the people within it face. People will come to you, explain their problems, and ask for your help in solving them.

Overnight Success Is a Myth

It took me a long time-until writing this book!-to realize how important communities were to my career. The Gumroad origin story I tell starts with me working as an early engineer at Pinterest. A few months in, on a Friday night, I was at home learning how to design a photorealistic icon for a side project. I came up with this:

I spent four hours, if I recall correctly. But if I had had a source file to work from, something to see how all the shadows and highlights and shapes came together, it would have taken me half that time. I would have totally paid money for that, at least a buck. And because I was part of a community of like-minded designers, I knew many others would too. Not only that, but a subset of those designers followed me directly on Twitter-all potential customers.

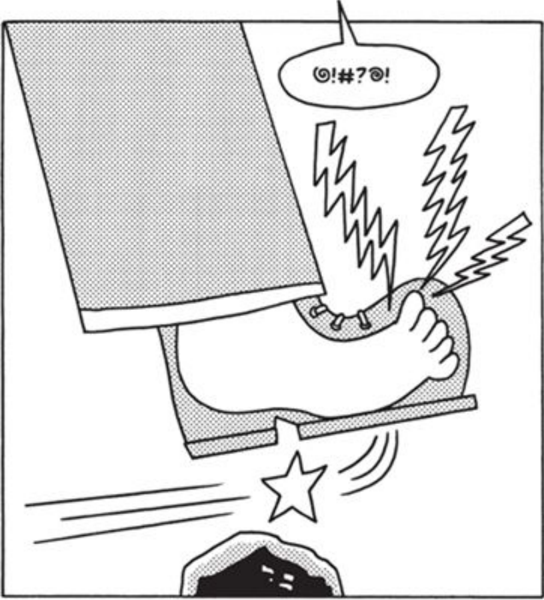

I looked around online, assuming it was going to be incredibly easy to sell something digital to my audience, but it wasn't. It would have required setting up a whole storefront and paying a monthly fee. I had stubbed my toe on a problem- a concept we'll explore in more detail later in this chapter.

I built Gumroad that weekend, launched it Monday morning, and even sold a few copies of that pencil icon.

But the classic origin story is incomplete. It turns out I had had a similar problem and thought process before, but I hadn't decided to build Gumroad then. In a blog post from 2012, I wrote about trying unsuccessfully to find a way to sell the source code for a Twitter client app I built for the iPhone. I searched for a solution for a few hours, but I couldn't find anything and gave up.

A lot had changed in the years between the first time I imagined what would eventually become Gumroad and the second time, but the most important shift was that I had found my communities and had established myself within them by creating, contributing, learning, and teaching. When I had the idea the second time around, I was armed with the confidence, audience, and insights to solve a meaningful problem quickly and effectively.

From the outside, it all seems so straightforward, but it took time not only to become part of the community but also to choose the community I wanted to serve and decide on the problem I wanted to solve. There's really no such thing as overnight success. Most are years in the making, just like my ability to build Gumroad over a weekend was also many years in the works.

When I was just getting started with web design, parents and teachers were my first clients (a social studies teacher needed a website for her books, while a parent needed help with the online presence of a local charity auction). Over time, I found like-minded web designers on web forums like TalkFreelance, self-described as a 'forum for web designers and freelance developers' interested in website design, programming, search engine optimization, and more. Later, I found Hacker News, a site where most of Silicon Valley congregated online. At first, I was a lurker, then a commenter, and then an active contributor. And because my Twitter account was in my profile, as well as in my email signature, I started to collect a small following of people who signaled their interest in following me !

Communities were essential for my personal development and career growth. They were where I made friends and formed business relationships. To this day, I am still meeting people who remember my name or handle from those years. I never had an agenda. I just knew I wanted to be part of Hacker News. And with their help, when I launched Gumroad that first Monday morning, it rocketed to the top of the front page of the site and stayed there all day. Even though that was just the beginning of my story, it was still confirmation that I had found my people and was where I belonged.

Picking the Right Community

Once you are part of a community, you can start to make a list of difficulties its members face, and you can think about how you could build a product or service to solve one or more of them.

Every community has a unique set of problems that's calling out for a custom-built solution. You're probably part of a number of communities, but when it comes to making an impact in a community in a way that leads to a minimalist business, you should focus on a community where you can (and want to): (1) create long-term value; (2) build relationships for decades to come; and (3) carve out a unique, authentic voice for yourself. For the minimalist entrepreneur trying to make an impact, community is a way to stay focused: Instead of changing the world, you can change your community's world.

It's not enough to pick any community; you also have to consider your own interests. There are many communities that you may be a part of, but that doesn't mean you want to dedicate a significant portion of your waking hours to solving their problems. Unless some element of the community and its problems overlap with something you're passionate about, it is unlikely you would be happy operating a business within the spacecontempt for your customers is not optimal.

There are two more important attributes that will decide which is the ideal community to focus on: how large the community is, and how much money they are willing to spend (said differently: the total addressable market, or TAM). The goal here is not to find the largest community with the most dollars to spend in order to capture 1 percent of it. Instead, you should find something right in the middle. Too small, and you won't be able to build a sustainable business. Too large, and it will cost too much money to get to sustainability in the first place-and you will attract or create competitors along the way, leading to a race to the bottom in product pricing that you may not survive.

The best way to win is to be the only. And the best way to be the only is to pick a group that is Goldilocks size, has problems they would pay money to solve, and is underserved (likely because it is too small for larger competitors to go after).

Tope Awotona, founder of Calendly, started three very different companies for three completely different communities before eventually building the scheduling software business in 2013. In 2020, Calendly posted nearly $70 million in annual recurring revenue, more than double its 2019 figure. But Awotona's first company was a dating app that never really got off the ground. The second was projectorspot.com, which sold (obviously) projectors, but sales were poor and margins small. He tried again with a third startup, selling grills, but as he says, 'I didn't know anything about grills and I didn't want to! I lived in an apartment, and never even grilled.' Not only was he not part of the grilling community, but he didn't even want to be!

He took a different approach to building Calendly. He had been a sales rep earlier in his career, and he knew the hassle of sending multiple emails to schedule meetings. He had even run into the scheduling problem while trying to sell his own products as an entrepreneur. As time went on and his other ideas failed to gain traction, he saw a gap in the marketplace and resolved to address it for the community of sales reps he cared about and understood. He says that 'the journey to creating something that's impactful, something that serves people, something that you know people are willing to open up their wallets and pay for-is not something that you can do just for money.' While lots of people have scheduling fatigue, Awotona focused on problems specific to sales reps, which helped him define a problem he could both solve and monetize.

What does that mean for you? First, get involved in those communities wherever they are, offline and online. Then, contribute, teach, and, most important, listen. Finally, use the filters above to make sure you are picking the right community to serve.

Then, your problem becomes: Which problem should I pick?

Picking the Right Problem to Solve

The late Clayton Christensen described picking the right problem to solve as an opportunity to help customers achieve what they hope to achieve in a particular moment. 'What [great companies] really need to home in on,' he wrote in a 2016 article for Harvard Business Review , 'is the progress that the customer is trying to make in a given circumstance- what the customer hopes to accomplish: the job to be done.'

For example, millions of people buy McDonald's milkshakes. Why? Because McDonald's found out that the job to be done was to accompany lonely drivers on their trips to work. 'Nearly half the milkshakes were sold in the very early morning. It was the only thing [the customers] bought, they were always alone, and they always got in the car and drove off with it.' This is one reason why McDonald's milkshakes are so viscous: so they last a whole, lonely car ride.

Now, the McDonald's marketing team can go into an office and create a problem that could potentially be solved only by their food. Then they can spend hundreds of millions of dollars on advertising to convince people that they have this problem, and that they too could 'hire' a milkshake to get the job done.

Christensen's idea of 'the job to be done' is sound, but Mc-Donald's is doing it in the wrong order. They didn't start with the customer; they started with the job to be done, and then sank a ton of money into making customers believe they needed that job to be done.

Minimalist entrepreneurs don't have millions of dollars, nor do they want to manufacture problems for people. Instead, we believe that people already have enough problems, and that our role is to help them get rid of one.

That is why it is so key to start with community. If you try to make something for everyone, you will likely end up making something that no one really wants or needs. Once you know the group of people you want to help, you will start to see their problems much more readily. There are more problems than businesses. You just have to find them.

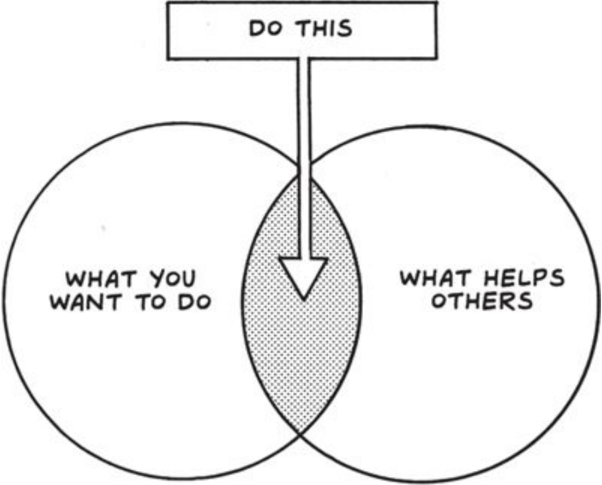

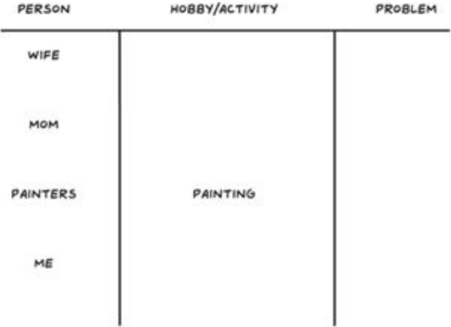

Still struggling? Grab a pen and paper. On the left, write down the person/community you would like to help. In the center, write down how they spend their time (buying onions, making icons of pencils on a Friday night, painting). On the right, write down the problems with each activity. It might look like the figure on page 46.

That blankness is like a blank canvas, or a blank page, or a blank business plan. You want to start a business to solve a problem, but you don't have any problems to solve.

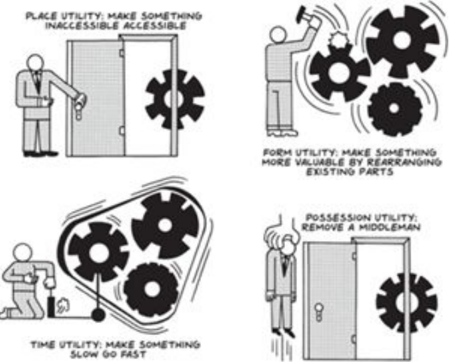

If you're struggling here (many do), some Economics 101 may help. There are only four different types of utility: place utility, form utility , time utility , and possession utility . What can you make easier to understand, faster to get, cheaper to buy, or more accessible to others?

- Place utility: Make something inaccessible accessible

- Form utility: Make something more valuable by rearranging existing parts

- Time utility: Make something slow go fast

- Possession utility: Remove a middleman

You are not trying to create problems for people in order to solve them, à la McDonald's. You are trying to discover inefficiencies in the lives of people you care about so you can help them. These may sound abstract, so let's put the four types of utility in context.

A business that farms coffee beans in Ecuador and sells them in San Francisco is changing the 'place' property of the beans. Place utility is what you are paying the premium for.

If a coffee shop buys beans from a wholesaler and grinds them up, their customers are paying a premium for form utility. (They are also, in theory, paying a premium for place utility if the coffee shop is closer to them than the distributor is. Of course, many businesses are a combination.)

If they also sell croissants that would take you three days to make, you are also paying a premium for time utility.

Finally, if you decide it's better for you to invest in a croissant-making machine to make your own croissants than to pay for them over and over again, that's possession utility.

One business that provides time utility is theCut, an app that connects barbers and clients and makes it faster and easier to find, book, and pay for services. Founders Obi Omile and Kush Patel came up with the idea after spending hours struggling to find barbers they liked and trusted. And getting an appointment with the best barbers often meant waiting hours because many used informal booking systems. TheCut provides utility for both sides. Clients save time, and barbers find new clients (possession utility), spend less time communicating with current ones (time utility), and receive mobile payments (form utility).

Omile and Patel built a great business because they understood the problems that plagued the community they planned to serve. Once you've picked your own community, the path to the right solution will become clear for you too.

Solving Your Own Problem

Everyone has problems, 'stubbing their toe' throughout their day. You may look around and think your life is pretty good, and maybe the folks around you do too. Or maybe the problems are obvious, and you already know what you want to build.

But most people, from my experience, miss these moments when they get whiplash from something being much harder or more painful than they initially expected. The brain adapts quickly, assuming the new state of things. It's meant to be this hard, it thinks, or there's a really good reason that it is, or it would be too annoying to change. I think that's the wrong way to go about life. Life is getting better all the time, and you can help accelerate the pace.

Basecamp had their own version of this moment when they were struggling to find the right tool to manage products with their clients. As founder Jason Fried says, 'We went looking for a tool to do this. What we found were ancient relics. To us, project management was all about communication. None of the software makers at the time seemed to agree. So we decided to make our own.'

When they launched, they were already an essential part of the online product management and web design community, with a well-read blog and dozens of clients. How did this help them?

In Jason's words: 'We decided early on that if we were able to generate around $5,000/month after a year (or about $60,000 in annual revenue), we'd have a good thing going. Turns out, we hit that number in about six weeks. So we absolutely were on to something.' When they had something ready to show their community, it turned out that many members had encountered the same roadblock.

If you have a problem, other people probably do too. Like many chefs, Nick Kokonas regularly faced the issue of lost revenue from no-shows at his Chicago restaurants. In a bid to solve his own problem, he cofounded Tock, which manages demand through traditional reservations but also through ticketing, which allows diners to prepay for reservations and special events and permits restaurants to create 'demand pricing' based on the desirability of reservation times. Prior to 2020, Tock was in thirty countries and two hundred cities, and was in use by thousands of restaurants, including some of the world's best. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Tock innovated further by launching Tock to Go, which allows customers to reserve and purchase restaurant meals for pickup from restaurants that may not have offered takeout or delivery ever before.

All of these businesses and many, many more hark back to community as a starting point. After all, if the problem you are solving for other people is also one you are solving for yourself, you will be able to kill a lot of birds with one stone. And if you build a product to solve your own problem, you will have at least one user-more than most startups ever get. Plus, you can talk to that user every single second of the day!

Building the Right Solution

Most businesses do not work, even if they are solving a real problem. This is often because while they are building something people want, they are not building it in the right way with the right minimalist mindset. So what kind of business can you build without a dollar of venture capital, appropriate to your skills and resources, in line with your mission, and viable in the marketplace?

It is also important to ask: If your business achieves its potential, what kind of positive impact might it make on the world? That, not the lure of an IPO, should be the guiding light for the founders of a company and all of its employees.

These are the criteria I use:

- Will I love it? Building a business is hard and time-consuming. It will take years. And the more successful it is, the longer you will work on it. So it's important to find something you want to work on, for people you want to work for. To build a successful business, you need to build something people love. To stick with it, you need to build something you love working on.

- Will it be inherently monetizable? There should be a clear path to charging people money for something of value, in a way that feels obvious. If it makes sense, it'll make cents.

- Does it have an internal growth mechanism? In 2020, Gumroad's revenues almost doubled due solely to word of mouth. In our case, it's impossible to use the product without sharing it with other people, and as a result, we've been able to 'outsource' our sales and marketing efforts because our customer base does the work for us as their customers use our platform. This is true of a lot of minimalist businesses, especially because you're going to build a great product people want to tell others about, and that they may eventually want to use themselves.

- Do I have the right natural skill sets to build this business? For example, if the business requires a lot of business development or sales calls to get off the ground, and you are deathly scared of speaking to anyone, then it's probably not a good fit for you. There are a lot of businesses waiting to be built-pick the right one for you.

No one book contains everything you'll need to know for starting any kind of business. The important thing is the thought process you bring to figuring things out for yourself. You need the right mindset and to know what questions to ask yourself. It begins and ends by thinking of your business as a tool to solve a customer's problem. Not as a lottery ticket.

Squashing Your Doubts

Finally, even though you have an idea you are excited about and are confident you can build, at some point you will have doubts. Surround yourself with colleagues and mentors who will not only tell you the truth but will also encourage you when the going gets tough. After all, people need cheerleaders, not just advice. Inspiring (and inspired) founders and leaders are not born, they are made. Almost anyone can do it, with enough patience, guidance, and sincerity.

A minimalist business can meet you where you are. It can grow with you as you grow (more on this in chapter 6). I would be lying if I said talent didn't matter at all, but what truly makes great founders and great businesses in the long term is a great deal of persistence. And one way to maximize your chances of success is to focus on a smaller product, on a community you are a core part of, and to be honest about whether you are solving the problem effectively or not. That's why a mindful approach to selling to a community you already have a relationship with is so important.

When you have doubts-and you will have doubts-go back to the fact that you've already started the work. By now, you will have (1) zeroed in on a mission-aligned problem to solve and (2) generated feasible ideas for a bootstrapped business that can tackle that problem profitably and sustainably. All you need to do from here, is to keep going.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- It's the community that leads you to the problem, which leads you to the product, which leads you to your business.

- Once you've found community-you fit, start contributing with the intention of becoming a pillar in that community.

- Pick the right problem (it's probably one you have), and confirm that others have it. Then confirm you have business-you fit too.

- When in doubt, always go back to the community. They will help you keep going and ultimately succeed.

Learn More

- Check out '1,000 True Fans,' a blog post by Kevin Kelly.

- Read Get Together , a book by Bailey Richardson, Kai Elmer Sotto, and Kevin Huynh.

- Read 'How We Gather,' a report by Casper ter Kuile and Angie Thurston.

- Listen to Calendly's Tope Awotona on Guy Raz's How I Built This podcast.

- Follow Anne-Laure Le Cunff on Twitter (@anthilemoon). She runs a successful online community for makers, community builders, creators, and more.