Introduction

- 1 The Minimalist Entrepreneur

- 2 Start with Community

- 3 Build as Little as Possible

- 4 Sell to Your First Hundred Customers

- 5 Market by Being You

- 6 Grow Yourself and Your Business Mindfully

- 7 Build the House You Want to Live In

- 8 Where Do We Go from Here?

One More Thing

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

contents

INTRODUCTION

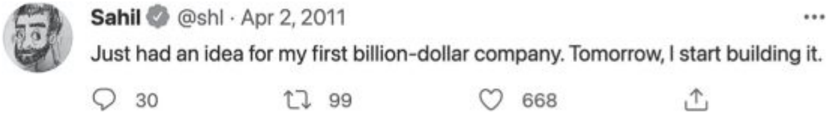

I started my career chasing unicorns. I joined Pinterest as employee number two, but in 2011, I left before my stock vested to build my own billiondollar company.

I had spent a weekend building the prototype of Gumroad, a tool that helped creators sell their products online. No complicated setup. No elaborate storefront. Just a link for customers to pay and you're in business. More than fifty thousand people visited the site on the first day, and I was sure I was on the cusp of something big.

The first step: raising money from VCs. As a nineteenyear-old solo founder, I found myself walking up and down the mythical Sand Hill Road, sweating through my jeans, having meetings in the same rooms where the decisions to fund companies like Netflix, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Google had happened. I ended up raising more than $8 million in venture capital from renowned Silicon Valley investors, including Accel Partners (early investor in Facebook), Kleiner Perkins (early investor in Google, Amazon, and Apple), Max Levchin (cofounder of PayPal), Naval Ravikant (cofounder of AngelList), and Chris Sacca (early investor in Twitter, Square, and Uber). They too thought they saw a unicorn galloping in the distance.

The chase was on. In short order, I built a world-class team-recruiting talent out of companies like Stripe, Yelp, and Amazon-and together we went to work on building a world-class product. I was confident that I'd soon be strolling through Allen & Company's annual Sun Valley conference, strategizing about the fight against malaria arm-in-arm with Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. I was never in it for the money, I told myself. I wanted to make an impact, but quietly. When I became a tech titan, I was going to be the kind of titan magazine profiles called 'down-toearth.'

I didn't make it to Sun Valley that summer. Or the summer after that. The closest I ever got to Bill Gates was watching him speak at a Kleiner Perkins CEO summit. Gumroad's pitched flight into the stratosphere leveled off after we burned through about $10 million in venture capital. After nine months of trying to raise more funding, we failed. In October 2015, I laid off three-quarters of the staff-including many good friends.

Once the bleeding stopped, it was time to reassess. Gumroad was still operational, but I felt like a complete failure. With many in my circle still focused on raising money, hiring employees, and chasing their own billiondollar companies- some successfully-I couldn't bear to stick around Silicon Valley. For much of 2016, I kept my apartment in San Francisco but spent most of my time traveling and writing fiction, convinced that even if I couldn't hack it in Startupland, I could still build a life for myself as a digital nomad. While I was inspired by Tim Ferriss's The 4-Hour Workweek , it didn't take long to realize that operating Gumroad as a lifestyle business wasn't for me. I was still trying to figure out what came next when I saw a tweet from Brandon Sanderson, one of my favorite authors, about a science-fiction and fantasy writing class he was teaching in Provo, Utah. In January 2017, I jumped on the opportunity to save rent and save face by moving to a place where no one knew me. There, I could figure out how to regroup even as I kept Gumroad afloat.

I knew things would be very different in Provo, but the contrast still surprised me. In San Francisco, being successful means you've made a lot of money (which, in San Francisco, is a lot of money). In Utah, it means you're married and active in the church. My new Provo friends told me that I'd been crazy trying to build a billion-dollar company in the first place.

Why wasn't Gumroad good enough as it was? After all, I had a sustainable business serving a group of customers I loved. What more could I want?

At first, I couldn't quite grasp what they were talking about, but after living in Provo for a couple of years away from the white-hot epicenter of venture capital, I came to agree. While the unicorn I was chasing turned out to be more of a Shetland pony, my original vision was being realized. Thousands of creators were using Gumroad to build their own creative businesses. Real people in the real world were paying their mortgages or topping off their kids' college funds or simply paying for a few extra lattes by selling courses, ebooks, and software online.

Over time, I realized that the problem wasn't Gumroad, the problem was me. I was still so focused on that elusive unicorn, I couldn't see the thriving business humming along right in front of me. Gumroad was profitable, the right size for its market, and enabling more and more writers, coders, crafters, and other makers to achieve their dreams with each passing day. Gumroad may have been a crappy investment for a few venture capitalists, but it was still a great company for its customers.

In the year after the layoffs, when I worked by myself, Gumroad still sent approximately $40 million to our creators, without any content marketing or paid advertising. Just creators telling other creators. When I recommitted to growing the company again in 2019, I continued to say no to those things I had said yes to previously, and focused solely on what would create more value for our creators. (Namely, shipping a better product.) It worked: In 2020 Gumroad sent more than $140 million to our creators, up 87 percent over the year before, all while remaining profitable.

Companies like mine may not grace the covers of glossy magazines or inspire Hollywood biopics, but they drive real, positive change and empower their founders, customers, and employees alike. I know that now, but it took me years to decouple my self-worth from my net worth and to realize that I hadn't failed. I had succeeded.

In February 2019, I wrote about my experience in a Medium essay, 'Reflecting on My Failure to Build a Billion-Dollar Company,' that struck a chord with millions. Since then, I've had the chance to connect with entrepreneurs and aspiring entrepreneurs who, deep down, would much rather build a sustainable business like Gumroad than chase a unicorn. They just think it's weird and uncool to express that desire when the media and our bigger-is-better culture keeps telling them that a unicorn is the only kind of business worth creating.

While that may be the right path for some companies, for many more it's not. Yet plenty of early-stage startups still end up raising venture capital because they can't fund their businesses in a sustainable way through profits. As a result, they're locked into the pursuit of huge, winner-take-all markets where growth is the most important asset of their businesses, not revenues, profits, or sustainability.

To help me reconcile those differences, I asked myself certain questions over and over again: What do I actually care to change? If I could fix one thing about my corner of the world, what would that be? What kind of business do I really want to build, own, and run?

Other founders and future founders have asked themselves similar questions and come to similar realizations. Many of their stories are included in this book. I call these people 'minimalist entrepreneurs,' and I call their companies 'minimalist businesses.'

Building a minimalist business does not mean settling for second best. Instead, it's about creating sustainable companies that have the flexibility to take risks to serve the greater good, all while empowering others to do the same. Being profitable, hopefully from the very beginning, means being able to focus and to stay focused on the reason you started a business in the first place: to help others.

Historically, entrepreneurs have played a crucial role in driving technological and social progress. This is even more necessary today, when big corporations are required by law to prioritize shareholder value over, among other things, actual value. In researching this book, I've found countless examples of businesses such as Basecamp, Wistia, Missouri Star Quilt Company, and many other honest-to-goodness, highly scalable companies incredibly focused on solving meaningful problems with beautiful products, services, and software that people love-and making a profit doing it. Each company goes about things their own way depending on the specific community they're building for, but they all focus on problem-solving and not taking themselves too seriously. No matter their differences, we can learn from them all.

Unfortunately, the word 'entrepreneur' has a weird taint to it. I remember going to a 'Career Fair' at school and not identifying with the 'entrepreneurs' at all. They seemed like businessmen (they were always men), and I didn't even like business. I liked making things! Eventually I realized that a business is not an end in and of itself. A business is a tool to make or do stuff, a legal structure; that's it. At first I didn't need a company, but eventually my creations required a legal structure, a team, and an operation to make the stuff I wanted to make, so I started a business.

When I made my transition from unicorn chaser to minimalist entrepreneur, I had to wrap my head around another new normal. This book is about deconstructing the myths we tell ourselves about the best way to build impactful businesses to change the abstract, singular 'world,' and about seeking the truth about how to build the businesses that will make us and our communities wealthier, healthier, and happier.

In the end, my failure to launch Gumroad into the stratosphere was the best thing that ever happened to me, because it taught me the very real consequences behind a 'growth at all costs' mindset. Unfortunately, it took me eight years, and a lot of pain, to realize it. I hope this book will help other aspiring entrepreneurs learn the lessons I learned without the painful layoffs and years of soul-searching. The overwhelming response to the viral essay I wrote about my experience is more proof that this promise resonates with many.

This book, part manifesto, part manual, will help you design, build, and successfully grow your own right-size business. Read it again and again, especially when you feel stuck. But keep in mind that you definitely do not need to finish this book to start . Start as soon as you can. Start before you feel ready. Start today.

You don't learn, then start. You start, then learn.

Now, let's get to it!

the minimalist entrepreneur

the minimalist entrepreneur

The beginnings of all things are small.

- CICERO

Atlanta-based web developer Peter Askew loves to get things off the top shelf at the supermarket for people who can't reach the same heights he can. A six-foot-eight former high school basketball star, Askew sees being helpful as the pillar of his business strategy, but it wasn't always that way. When the dot-com bubble burst in 2001 and he was laid off from eTour, a websurfing guide he helped build and grow, he had to ask himself, 'Is this how I want to live? Is this how I can be of service to the world?'

He knew he could get another job thanks to his background in marketing analytics, but he was also disillusioned. Money and prestige were not nearly as important to him as independence and freedom. Eventually he wound up with another role in advertising where he was exposed to a wide range of business models as thousands of new web businesses came online, but in the evening and on weekends, he threw himself into his side projects, learning about web development, domain names, and how to monetize web traffic.

That's how he stumbled on an idea that would change his life. What if instead of buying new domain names, which often took months to rank highly in search engine results, he bought expired domain names, which already had some degree of visibility? Other people were parking ads on expired domains or flipping them, but Askew had something else in mind, the seed of an idea that was driven by the questions he had started to ask himself about his work. Rather than trying to make a quick buck, he would build real businesses around domain names, asking himself with each one, 'Do I feel inspired? Is there a real business here?,' and, most of all, 'Can I be helpful?'

He experimented with randomly created names and ventures that didn't quite work before he realized that 'the domain name always comes first, the business idea comes second.' In 2009, that domain name was duderanch.com. Askew bought it and launched a directory, traveling to more than fifty dude ranches to meet the owners of the destinations he featured on his site. Eventually he partnered with the owner of guestranches.com, and the two built a curated list of destination ranches around the country. The success of that venture, which he worked on for ten years and sold in 2019, gave him the time and financial freedom to buy more domain names and develop other niche businesses. Some succeeded, others didn't.

In 2014, Askew saw that VidaliaOnions.com was up for auction. Until then, he had focused on information-based businesses, but something about the domain name appealed to him. So did the onions, frankly. As a Georgia native, he knew of Vidalias-a sweet, mild variety that some fans eat raw like an apple. The only trouble was that he didn't know anything about the onion business. Or farming in general, for that matter.

Regardless, he put down a $2,200 bid, confident that someone in the business would come in higher. (If bidding on interesting domain names like this sounds like a neat hobby, you may be a minimalist entrepreneur.) When he won the auction five minutes later, he was pleasantly surprised, but he filed it away for later and went back to work on other projects.

As the days went by, though, he couldn't stop thinking about Vidalias. '[The domain] kept nudging me,' he writes in his essay 'I Sell Onions on the Internet,' and 'after a month, I began to understand what it was telling me. That I buy pears from Harry & David every year, and I should mimic that same service for Vidalia onions. Instead of farm-to-door pears, farm-todoor Vidalia onions.' He saw a way he could be helpful to others, and a new minimalist business was born.

Askew didn't eat Vidalias himself, but he knew that many people did, both from his own experience and from strong search volume for the phrase on Google Trends. But he still had his doubts. 'I'm not a farmer,' he worried. 'I have no logistics or distribution system setup.'

He got started anyway. His first step was to reach out to a trade group that put him in touch with Aries Haygood, the owner of an award-winning Vidalia farm in operation for over two decades that had, crucially, a packing shed. He used his own money to put up a new site on VidaliaOnions.com, and then, '[while] the farm concentrated on the Vidalia, I concentrated on customer service, marketing, branding, web development, & logistics,' he recalled. 'I didn't have other projects that were this front-facing, customer wise. And I discovered I immensely enjoyed it.'

Askew and Haygood estimated fifty orders for their first season. They received more than six hundred.

It would be at this point in the life cycle of a VC-funded business that the investors would start getting frisky. 'Six hundred orders when we expected fifty?' they'd exclaim. 'Time to quintuple your hiring. Come to think of it, what does the international market for Vidalia onions look like? A few million in ad spending, a viral video, and we'll have Vidalias trending worldwide. We'll probably need people on the ground in London, Tokyo, and Sydney. Time to raise another round.' And on it goes. Picture a little kid blowing a balloon up for the first time, until . . .

Askew himself couldn't help but consider trying to accelerate the company's growth, but he stuck to what he had learned over the years and focused instead on profitability. He knew that the previous owners of VidaliaOnions.com had gone belly up trying to sell salad dressings and relishes in addition to the onions themselves. So instead, he slowly built the business in front of him, figuring out how to sell Vidalia onions to the market of potential customers within the range of timely and affordable shipping from that one packing shed.

He made mistakes, of course. At one point, he lost thousands of dollars on faulty shipping boxes, an error that nearly shuttered the operation. But he also made small process improvements year by year, like implementing an automated shipping system rather than manually entering customer orders and printing UPS labels. A few years in, the business was profitable, growing organically at its own pace, and he was having fun.

Six years in, Askew's pet project has become a full-fledged business, which makes his many customers happy and has a positive impact in the local community. He no longer sees it as just another experiment along with all of his other cast-off domain names. VidaliaOnions.com is becoming his mission:

Honestly, my customers would be quite upset if we disappeared. Last season, while I called a gentleman back regarding a phone order, his wife answered. While I introduced myself, she interrupted me midsentence and hollered in exaltation to her husband: 'THE VIDALIA MAN! THE VIDALIA MAN! PICK UP THE PHONE!'

At that moment, I realized we were doing something right. Something helpful. Something that was making a positive impact. . . . It's immensely gratifying. I feel so fortunate to be associated with this industry.

Maybe it's the onions, but Askew's story brings a tear to my eye. There is something profoundly beautiful in a value-oriented mission and a genuine purpose driven by your own lived experience. This is what being a minimalist entrepreneur is all about: making a difference while making a living.