Chapter Nine

PREFRONTAL CORTEX

Assuming that the human capacity for high-level abstraction is because of the expansion of the neocortex, which aspects of the human neocortex are critical for that ability? Does it feature special types of neurons or special neural circuits? Is there a special region in the human neocortex that is absent in other animals? Or does the capacity for innovation emerge from its global organization? We do not have clear answers to these questions, even though higher brain functions are generally believed to be outcomes of emergent properties of neural circuits rather than properties of individual neurons. One major reason for our ignorance on this matter is the absence of a decent animal model. Studies using animals greatly advanced our understanding of the neural bases of memory and imagination. In fact, for most brain functions, our understanding of their underlying neural mechanisms is owed greatly to animal studies. Obviously, this cannot be the case for the brain functions that are unique to humans, such as higher-order abstract cognition. Nevertheless, we are not without clues on this issue. Here, we will examine a few of these as samplers rather than exhaustively going over all of them. We will examine three clues: one derived from neuroscientific research (this chapter), another derived from paleoanthropological work (chapter 10), and the final one derived from neural network modeling (chapter 11).

EXECUTIVE FUNCTION

Which brain structure would a neuroscientist say is most likely to play a crucial role in high-level abstract cognition in humans? Most neuroscientists would be reluctant to bet on one brain structure. Nevertheless, if they were forced to do so, perhaps a considerable number would pick the prefrontal cortex—the foremost part of the cerebral cortex (see fig. 9.1). Adjacent to the prefrontal cortex are premotor and supplementary motor cortices, which are known to play crucial roles in, roughly speaking, movement planning. These cortices project heavily to the primary motor cortex, which oversees the direct control of voluntary movement. As one may guess from this organization, the prefrontal cortex is an important brain structure for the control of behavior. However, the prefrontal cortex is not directly involved in the control of specific movement per se. Rather, the prefrontal cortex controls behavior flexibly according to internal goals and behavioral contexts.

The prefrontal cortex may promote a specific behavior in one circumstance but inhibit it in another. For example, in New York, you should look left before crossing a street to check for passing vehicles. However, in London, you should look right before stepping off the curb. Hence, in London, New Yorkers must suppress their habitual behavior of looking left to check for cars before crossing the street. This simple example illustrates the importance of a context-dependent control of behavior in our daily lives.

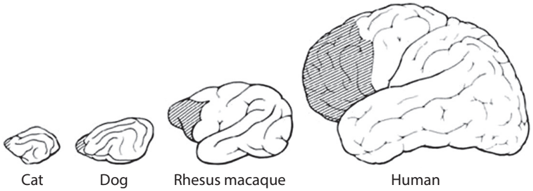

FIGURE 9.1. Prefrontal cortex, indicated in shading, in several different animal species. Figure reproduced with permission from Bruno Dubuc, 'The Evolutionary Layers of the Human Brain,' The Brain from Top to Bottom, accessed December 11, 2022, https://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/a/a_05/a_05_cr/a_05_cr_her/a_05_cr_her.html.

Controlling behavior flexibly according to an internal goal in an ever-changing world is not a simple job. A diverse array of functions is required to be able to do that. Not surprisingly, previous studies have found that the prefrontal cortex serves a wide range of cognitive functions: working memory, reasoning, planning, decision-making, and emotional control; the term executive functions collectively describes the functions of the prefrontal cortex.

It controls and coordinates other functions of the brain so that our behaviors, or suppression of them, serve the role of achieving our internal goals. It would be impossible without the prefrontal cortex to work day and night to achieve your long-term goal, such as getting a doctoral degree in neuroscience in five years. As you may have guessed, the prefrontal cortex is well developed in primates, especially in humans. One could argue that the prefrontal cortex differentiates humans from other animals. When we look at the behaviors of people whose prefrontal cortex has been damaged in some way, this becomes abundantly clear.

PHINEAS GAGE

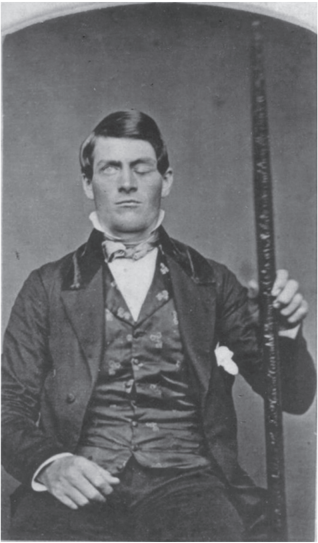

Phineas Gage was a foreman in a crew cutting a railroad bed in 1848 in Vermont. He was twenty-five years old at the time. The crew blasted rocks by boring a hole deep into a rock, adding explosive powder, and then packing inert material, such as sand, into the hole with a tamping iron. On September 13, probably because Gage inadvertently omitted adding sand, the powder exploded because of a spark between the tamping iron and the rock. The tamping iron, just over three and a half feet long, passed through Gage's head and landed over eighty feet away. Miraculously, he survived the accident and, surprisingly, could speak and walk a few minutes later. So what were the consequences of this accident? Gage had no problem seeing, listening, speaking, or moving around. The tamping iron damaged the foremost region of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (see fig. 9.2), indicating that this region of the brain is not needed for brain functions such as life support, sensation, motor control, or language.

Nevertheless, Gage's personality changed dramatically following the accident. He used to be a smart, energetic, and shrewd young man with a promising future and was considered the most efficient and capable man in the company. However, after the accident, he was 'no longer Gage' to his friends. Dr. John Harlow, who treated Gage for a few months, recorded the following notes:

The equilibrium or balance, so to speak, between his intellectual faculties and animal propensities, seems to have been destroyed. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity which was not previously his custom, manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operation, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned. . . . A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animal passions of a strong man.

FIGURE 9.2. Brain injury of Phineas Gage. (Left) A tamping iron traveled through Gage's brain. Panel reproduced from John M. Harlow, 'File:Phineas gage-1868 skull diagram.jpg,' Wikimedia Commons, updated October 25, 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phineas_gage_-_1868_skull_diagram.jpg; (right) Gage holding the tamping iron that injured him. Panel reproduced from 'File:Phineas Gage GageMillerPhoto2010-02-17 Unretouched Color Cropped.jpg,' Wikimedia Commons, updated August 2, 2014, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phineas_Gage_GageMillerPhoto2010-02-17_Unretouched_Color_Cropped.jpg.

Previous to his injury, though untrained in the schools, he possessed a well-balanced mind, and was looked upon by those who knew him as a shrewd, smart business man, very energetic and persistent in executing all his plans of operation. In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was 'no longer Gage.'

PERSISTENCE AND FLEXIBILITY

To achieve a long-term goal, one must be persistent yet still flexible rather than 'obstinate, yet capricious,' which was how Harlow described Gage. Suppose you need to buy groceries to make dinner for a friend. Your plan is to buy steak and garlic because your friend's favorite dish is garlic steak. You arrive at the store and find many delicious-looking food—bread, pasta, fish, and fruit—on your way to the meat section. You must be persistent and ignore all these distracting stimuli and achieve your original goal (getting the ingredients for the garlic steak). This wouldn't be difficult for neurotypical people, but it would be for those living with prefrontal cortex damage since they are easily distracted by intervening stimuli. In this example, they may buy any items that catch their attention, such as salmon and pasta, instead of steak and garlic. In fact, some may not even be able to get to the store in the first place. They may get on a random bus that happens to stop by them on their way. This example illustrates the importance of the prefrontal cortex in making us persist in achieving a long-term goal.

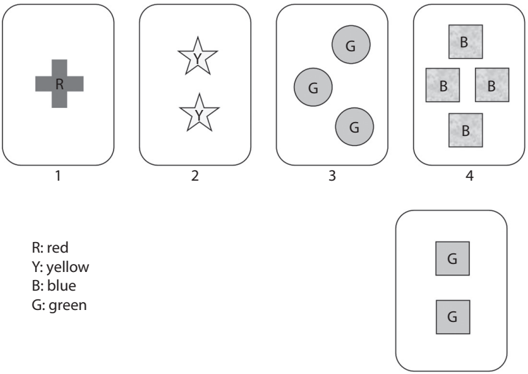

The prefrontal cortex is important not only for persistence but also for flexibility. If a certain behavior is no longer effective in achieving your current goal, you must switch to another type. If you stick to behavior that is no longer effective, you would be considered obstinate rather than persistent. People with prefrontal cortex damage have trouble changing their behavior according to changes in the environment. This can be tested with the Wisconsin card sorting test, a neuropsychological test frequently used to measure perseverative behaviors (insistence on wrong behavior). In this task, the subject must classify a stimulus card according to a hidden rule that changes over time. Figure 9.3 shows a sample computer screen of the task. The subject must match the sample card shown in the bottom right corner of the screen (the card with two green squares) to one of the four cards on top. Possible hidden rules are the color, quantity, and shape of the figures in the card. The hidden rule is not revealed to the subject. The subject is only told whether their match was right or wrong. In the example shown, the right match may be the second card (hidden rule: number), the third card (hidden rule: color), or the fourth one (hidden rule: shape). People with no prefrontal cortex damage quickly adjust their matching strategy based on the feedback ('wrong') when the current hidden rule changes. However, after getting that feedback (i.e., when the hidden rule changes), people with prefrontal cortex damage tend to stick to the old matching strategy that no longer yields a correct match.

FIGURE 9.3. Wisconsin card-sorting test.

PREFRONTAL CORTEX AND ABSTRACTION

Abstraction is essential for guiding behavior according to a long-term internal goal, for changing behavior flexibly according to hidden rules, and for reasoning and planning, all of which are functions of the prefrontal cortex. Indeed, patients with prefrontal cortex damage show impaired abstraction in various clinical tests. For example, in a proverb interpretation task, patients may have trouble understanding a statement in an abstract sense. 'Rome was not built in a day' may be interpreted in a concrete sense (e.g., the time it takes to complete the infrastructure of the Roman Empire) rather than an abstract sense (the time it takes to accomplish great achievements).

Consistent with these neuropsychological findings, physiological studies of the prefrontal cortex have found abstraction-related neuronal activity even in animals. Neurophysiologists who study the prefrontal cortex joke that the prefrontal cortex is like a department store, meaning that you can usually find whatever neural signals you are looking for if you stick a microelectrode in the prefrontal cortex. Why is that so? As we saw with Phineas Gage, the prefrontal cortex is not specialized to process specific sensory or motor signals. Rather, it represents the information necessary to complete a given task successfully. The information varies widely depending on the current goal and includes not only specific sensorimotor signals but also abstract concepts, such as task rules, that are needed to achieve the goal. In other words, the prefrontal cortex appears to be a general-purpose controller that flexibly and selectively represents the information essential to control a goal-directed behavior. Hence, if you train an animal to perform a certain behavioral task, you are likely to find concrete as well as abstract neural signals essential to perform the task in the prefrontal cortex.

Numerous studies have shown diverse types of abstraction-related neural activity in the prefrontal cortex of animals. Here, as an example, let's examine the representation of number sense in the monkey's prefrontal cortex. Numerosity, the number of elements in a set, is an abstract category that is independent of physical characteristics of elements. For example, 'threeness' is an abstract concept that is applicable to any set containing three elements regardless of their modality. Neurophysiological studies in monkeys have found neurons in the prefrontal cortex that are selectively tuned to the number of items. In one study, Andreas Nieder trained rhesus monkeys to discriminate the number of sequentially presented items to obtain a reward. The items were presented in two different formats: sound pulses (auditory) or black dots (visual). He found neurons in the prefrontal cortex that are tuned to the number of items irrespective of the modality of the stimuli. Each numerosity-coding neuron is preferentially responsive to a particular number so that a group of prefrontal cortex neurons can provide unambiguous information about the number of successive stimuli presented to the monkey. This and other related studies clearly show that the monkey's prefrontal cortex represents number sense, which is an abstract category beyond physical characteristics of elements.

Neural activity related to abstract concepts, such as task rule, task structure, and behavioral context, has been found even in the rat and mouse prefrontal cortex. A rodent's prefrontal cortex is tiny compared to a human's. Not only the absolute size but also the size relative to the whole brain is much smaller for a rodent than a human. Even so, rodents do show considerable levels of sophisticated behavioral control that are needed to achieve a long-term goal. For example, damages in the prefrontal cortex impair flexibility in a rodent version of the Wisconsin card-sorting test. These animal studies show clearly that the rodent prefrontal cortex, very underdeveloped compared to the human prefrontal cortex, supports flexible control of behavior and represents abstract concepts. It is conceivable then that the well-developed human prefrontal cortex may represent much higher-level abstract concepts than those found in animals.

One domain of behavioral control where high-level abstraction is necessary would be human social behavior. Gage's behavior after his tragic accident was far from expected for a normal adult. It would be extremely difficult for 'a child in his intellectual capacity' to behave properly in a complex human society. Our social behaviors are outcomes of careful considerations of subtle social conventions that vary widely according to social contexts; therefore, abstract thinking is essential. For example, we routinely use high-level abstract notions such as public order, rudeness, and social reputation to decide how to behave every day. It may be that the human capacity for high-level abstract thinking owes a lot to, among other things, the evolutionary pressure to form and represent high-level abstract concepts for the proper control of behavior in a complex human society.

To summarize, there are good reasons to suspect that the well-developed human prefrontal cortex is a core region of the neural system forming and representing high-level abstract concepts. Of course, it is not likely that the expansion of the prefrontal cortex is solely responsible for our enhanced abstract thinking capacity. Other changes in the brain are likely to be crucial. For example, the parietal cortex is activated together with the prefrontal cortex during various abstraction tasks. Thus, understanding how the prefrontal cortex interacts with other brain areas is also important to understand the neural basis of human abstraction.

FRONTOPOLAR CORTEX

Another important issue is which subregion of the prefrontal cortex plays the most crucial role in abstraction. The prefrontal cortex is a large area consisting of multiple subregions serving distinct functions, and it is unclear how the abstraction function is distributed across these subregions.

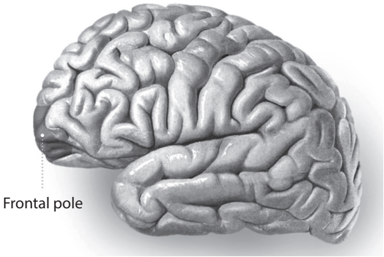

FIGURE 9.4. Frontopolar cortex. Figure reproduced from Frank Gaillard, 'Frontal Pole,' Radiopaedia.org. rID: 46670, accessed April 6, 2023, https://radiopaedia.org/articles/34746 (CC-BY-NC-SA).

Brain imaging studies suggest that more anterior (frontal) parts of the prefrontal cortex serve more abstract thinking and more posterior (rear) parts serve more concrete thinking. If so, future studies focusing on the frontopolar cortex (see fig. 9.4), the most anterior region of the prefrontal cortex, may provide important clues to our quest to elucidate the neural basis of human innovation.