Chapter Eight

ABSTRACT THINKING AND NEOCORTEX

In chapter 7, we entertained the idea that the mammalian hippocampus has evolved to simulate (i.e., imagine) novel spatial trajectories to meet the unique ecological demands of land navigation. Human imagination, of course, is not limited to exploring novel spatial trajectories. We may imagine a story of a doctor who fell in love with two women during the turmoil of the Russian Revolution, imagine a new solution for the Riemann hypothesis, imagine artistic expressions that capture the fundamental loneliness of existence, imagine ourselves watching a clock while traveling at the speed of the light, and so on. Our unlimited capacity for imagination using highly abstract concepts is perhaps the most important element of our mental capacity that makes us particularly innovative.

ABSTRACT THINKING

How have humans, Homo innovaticus, acquired this capability? I argued that the hippocampus of land-navigating mammals evolved to simulate diverse navigation trajectories. If so, imagination per se is not a mental faculty unique to humans. Also, considering that the hippocampus processes not only spatial but also nonspatial information even in rats, the content of animal imagination probably includes both components. It is likely then that the capability to imagine future events, both spatial and nonspatial, is a function shared by most mammals. If so, our superb capacity for innovation is unlikely due to our unique ability to imagine future events. Rather, it is more likely due to our exceptional capacity for high-level abstraction. In other words, the superiority of human innovativeness is likely the result of combining high-level abstract thinking with the already existing imagination function.

Abstract thinking refers to the cognitive capacity to derive general concepts or principles from individual cases. It allows us to form and manipulate concepts that are not tied directly to concrete physical objects or events, such as love, imaginary numbers, democracy, and free will. And it is not a unique mental faculty of humans; abstract thinking is pervasive in the animal kingdom. Nature is not random. Many animals figure out regularities in their environment, represent them as general rules, and behave accordingly to maximize survival and reproduction. Many animals also understand abstract notions such as numbers, are capable of transitive inference (e.g., if A > B and B > C, then A > C), and show behaviors suggesting self-awareness and theory of mind (the ability to attribute mental states, such as beliefs and intents, to others; e.g., 'I know what you are thinking'; see chapter 1). Neurophysiological studies have also found neural activity related to categories, high-order relationships, behavioral rules, and social interactions in rats and monkeys. A specific example of the neural representation of an abstract concept (number sense) will be shown in chapter 9.

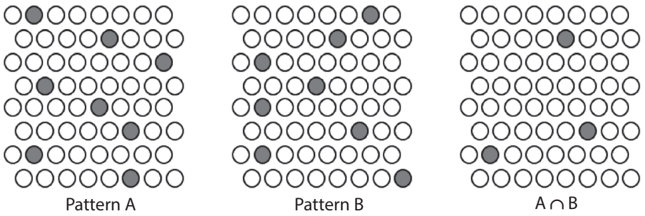

If we consider how a neural network stores experiences as memories, we can admit that abstraction is inevitable even in animals. Researchers generally believe that neural networks store multiple memories in an overlapping and distributed manner (see fig 8.1 and also fig. 4.3). If a neural network experiences many similar stimuli (such as many cars), those synapses (i.e., neural connections) activated by common features of these stimuli (e.g., their 'car-ness') will be strengthened more than other synapses because they will be repeatedly activated. Then those neurons having a sufficiently large number of the strengthened synapses will be preferentially activated by any of these stimuli. In other words, some neurons will be responsive to any car, be it familiar or novel, because they will be responsive to common features of cars after sufficient experiences. This enables us to recognize an object we have never seen before as a car. As this example illustrates, generalization, which is a form of abstraction, is thought to be a spontaneously emerging property of a neural network in animals and humans.

FIGURE 8.1. Overlapping and distributed representation of memories in a group of neurons. One memory activates multiple neurons, and one neuron may participate in multiple memories.

INNATE ABSTRACTION

The car example is a case for empirical abstraction. Neurophysiological studies have also found evidence for innate abstraction in animals. An eighteenth-century German philosopher, Immanuel Kant, claimed that humans are born with innate principles of cognition. This contrasts with the view of empiricism, which is traced back to Aristotle: knowledge comes primarily from sensory experiences rather than innate cognition. Kant, paralleling his proposal to the Copernican Revolution, claimed that we understand the external world based on not only experiences but also a priori concepts, things that can be understood independent of experience. He argued that space and time are pure intuitions rather than properties of nature. We consider space and time as physical entities that extend uniformly and infinitely in Cartesian coordinates because that's how we experience nature (i.e., the innate structure of cognition).

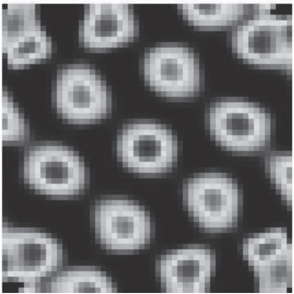

More than two centuries after Kant published the influential Critique of Pure Reason in 1781, neuroscientists found evidence for the intuition of spatial perception in the rat. The Norwegian neuroscientists Edvard Moser and May-Britt Moser, who shared a Nobel Prize with John O'Keefe in 2014, discovered 'grid cells' in the rat entorhinal cortex, the main gateway of the hippocampus (the hippocampus communicates with the rest of the cerebral cortex mostly via the entorhinal cortex; see fig. 4.1). A single grid cell fires periodically at multiple locations forming a hexagonal grid pattern of spiking activity as a rat moves around in each space (see fig. 8.2). This finding suggests a metric representation of the external space in the entorhinal cortex.

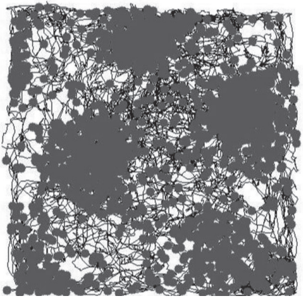

Importantly, a given grid cell maintains the same hexagonal grid firing pattern in all spaces. If you record the activity of one grid cell in two different rooms, the same pattern is observed in both (the generality of grid firing). The only difference is the orientation of the overall grid firing pattern across the two rooms (see fig. 8.3), indicating that the structure of spatial representation in the entorhinal cortex is identical regardless of where you are. Furthermore, if you record multiple grid cells simultaneously, their spatial relationships are preserved across multiple environments. In other words, all grid firing patterns rotate to the same degree when an animal is moved from one environment to another. This observation further corroborates the conclusion that the entorhinal cortex represents all external spaces in the same format, which is consistent with the notion of an a priori rule for spatial perception.

FIGURE 8.2. Activity of a sample grid cell. (Left) The black trace indicates a rat's movement trajectory, and gray circles indicate spike locations of the sample grid cell. Panel reproduced from Khardcastle, 'Grid cell image V2,' Wikimedia Commons, updated June 1, 2017, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grid_cell_image_V2.jpg (CC BY-SA). (Right) A spatial autocorrelogram was constructed from the sample grid cell activity to reveal a periodic hexagonal firing pattern. Panel reproduced from Khardcastle, 'Autocorrelation image,' Wikimedia Commons, updated Jun 1, 2017, accessed Dec 21, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autocorrelation_image.jpg (CC BY-SA).

FIGURE 8.3. A schematic for grid firing patterns of three grid cells recorded in two different rooms.

Firing fields of three grid cells

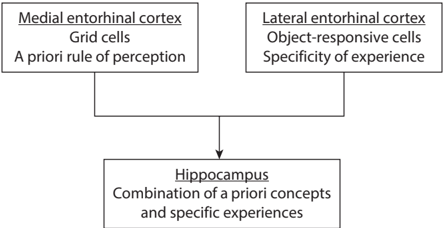

The entorhinal cortex consists of two divisions: medial and lateral. Grid cells are only found in the medial division. In the lateral division, neurons are responsive to objects encountered in each environment, such as a visual landmark, suggesting that they encode specifics of an environment. The inputs from the lateral and medial entorhinal cortices converge in the hippocampus. This way, the hippocampus appears to combine two different types of inputs regarding spatial perception—one carries a general metric representation of space (medial entorhinal cortex) and the other carries information about specifics of an environment (lateral entorhinal cortex). This suggests that the hippocampus combines two different types of information: abstract structural knowledge and individual sensory experiences that are provided by the medial and lateral entorhinal cortex, respectively (see fig. 8.4). Studies in humans have shown that grid cells may encode not only spatial information but also conceptual knowledge in a gridlike activity pattern. These results led Timothy Behrens and colleagues to propose that the entorhinal cortex's medial and lateral divisions, respectively, carry abstract structural knowledge and individual sensory experiences beyond the spatial domain. This idea parallels Kant's proposal that we understand the world by the interplay between experiences and a priori concepts.

FIGURE 8.4. A schematic showing the information flow from the entorhinal cortex to the hippocampus.

HUMAN ABSTRACT THINKING

Humans, as well as other animals, are capable of abstract thinking. Researchers have learned a lot about the neural processes that underpin abstraction in animals. However, no other animal is capable of humans' high level of abstract thinking. Our capacity for high-level abstraction is overwhelming compared to other animals. Language is a prime example. We manipulate symbols according to grammatical rules in our daily use of language. Other animals, of course, can communicate with one another. No animal communication system, however, comes close to the complexity and flexibility of human language. In conclusion, animals are capable of abstract thinking and, most likely, imagination in the abstract domain. However, their abstract thinking and imagination would be much more limited than ours.

Our thinking process routinely crosses concrete and abstract domains. We are born with the ability to think abstractly, so we do not need to make an effort to do so. To illustrate this point, let's examine the 'category mistake' proposed by the renowned English philosopher Gilbert Ryle. Ryle introduced the idea in the process of refuting Cartesian dualism, which argues that the mind and the body are two separate entities. So what is the category mistake? Let's assume that your friend is showing you around her university. She shows you libraries, cafeterias, dormitories, laboratories, and lecture rooms. Now you ask, 'But where is the university?' Of course, the university consists of all these things together. The university is a collection of institutions that may or may not be housed in their buildings. This example illustrates a semantic error in which things belonging to two different ontological categories (the university versus its buildings) are treated as though they belong to the same category. What is wrong with saying 'there are three things in a field: two cows and a pair of cows'? It's a category mistake, of course. Likewise, putting 'mind' and 'body' in the same category and assuming their existence as separate entities would be an example of a category mistake.

To me, these examples reveal our innate tendency to mix up concrete and abstract concepts and to consider abstract entities (such as 'university' and 'mind') as though they exist as concrete entities (such as 'library' and 'body'). This is probably a consequence of our ability to think seamlessly using both concrete and abstract concepts. Neural representations of concrete versus abstract entities may not be different according to the brain. After all, those representations are merely implemented by changes in neural connections (see fig. 4.3) and patterns of neural activity. This perspective further promotes the view that human capacity for innovation is a natural consequence of adding the capacity for high-level abstraction, which is unique to humans, to the capacity for imagination, which is common to all mammals.

HOW MANY NEURONS IN THE CORTEX?

How have humans acquired the capacity for high-level abstraction? One characteristic of the human brain is its size. We have large brains compared to other animals including nonhuman primates. For instance, the human brain is three times larger than the chimpanzee's. A larger brain harnessing more neurons allows for higher processing power. In other words, size does matter for the relationship between the brain and intelligence.

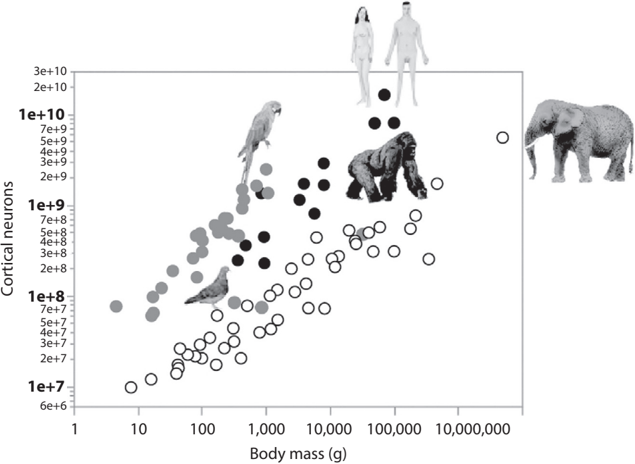

Size isn't everything, however. Elephants and whales have larger brains and more neurons than we do. Nevertheless, our intelligence is superior to those animals. How is this possible? The comparative neuroanatomist Suzana Herculano-Houzel has spent years counting the numbers of neurons in different areas of the brain across a wide variety of animal species. Her studies indicate that the way neurons are distributed in the brain varies substantially across animal species. For example, elephants have a brain three times larger than ours and, accordingly, have more neurons in the brain than us. In the cerebellum, which plays a crucial role in movement and posture control, elephants have far more neurons (251 billion) than humans (69 billion). The picture changes, however, if we examine the cerebral cortex. Humans have about three times as many neurons (16 billion) there as elephants (5.6 billion). Humans, in fact, have more neurons in their cerebral cortex than any other animal on the planet. While the cerebellum in humans contains about 80 percent of the brain's neurons, it only constitutes 10 percent of the brain's mass. On the other hand, the cerebral cortex contains less than 20 percent of all neurons, yet it makes up approximately 80 percent of brain mass. This is due to the cerebral cortex having larger neurons, more neural connections, and a greater number of glial cells compared to the cerebellum. As a result, the cerebral cortex has incredibly complex neural circuits. Considering the central role of the cerebral cortex in supporting advanced cognitive functions, it appears that humans are particularly intelligent and cognitively advanced as a result of their well-developed cerebral cortex.

Herculano-Houzel's studies indicate two advantages that helped humans to possess the largest number of neurons in the cerebral cortex. First, we are primates. The packing density of neurons in the cerebral cortex is much higher in primates than in other mammals. Chimpanzees, much smaller in body size than elephants, have about the same number of cortical neurons (6 billion compared to 5.6 billion). Orangutans and gorillas, also much smaller than elephants, have more cortical neurons (9 billion). Thus, primates appear to have found an efficient way to pack far more neurons into the cerebral cortex than other animal groups during evolution.

Second, we have the largest brain of all primates. Combined with those highly packed cortical neurons, our big brain allows us to have the largest number of neurons in the cerebral cortex (16 billion) of any animal on earth (see fig. 8.5).

FIGURE 8.5. Body mass versus the number of neurons in the mammalian cerebral cortex or bird telencephalon. The scaling rule for the power function relating body mass to the number of cortical neurons varies across animal groups. Black, open, and gray circles indicate primate, nonprimate mammalian, and bird species, respectively. Figure adapted with permission from Suzana Herculano-Houzel, 'Life History Changes Accompany Increased Numbers of Cortical Neurons: A New Framework for Understanding Human Brain Evolution,' Progress in Brain Research 250 (2019): 183.

EXPANSION OF THE NEOCORTEX

The cerebral cortex can be categorized into distinct evolutionary divisions. These include the archicortex (hippocampus) and paleocortex (olfactory cortex), which represent older divisions, as well as the neocortex, which represents a newer division (note that cerebral cortex is commonly used to refer to the neocortex, as in chapter 4). Do we imagine freely using high-level abstract concepts because our hippocampus (archicortex) has special features that are absent in other animals? As we examined in chapter 7, the structure of the hippocampus is remarkably similar in all mammals including humans (see fig. 7.1). Also, as we discussed in chapter 1, damage to the hippocampus leaves most brain functions other than memory and imagination largely intact. Furthermore, hippocampal injuries change the content of mind-wandering from vivid and episodic to semantic and abstract. Thus, it is not very likely that an idiosyncrasy of the human hippocampus is behind the unique human capacity for imagination using high-level abstract concepts.

One of the most outstanding differences between human and other animal brains is the relative size of the neocortex. The surface area of the hippocampus comprises 30-40 percent of the entire cortical surface area in rats but only 1 percent in humans. This is because the neocortex has expanded greatly in primates, especially humans. Primates evolved over 60 million years ago; apes evolved from African monkeys over 30 million years ago; great apes diverged from gibbons over 20 million years ago; humans (hominins) and chimpanzees split from the last common ancestors 6-8 million years ago. The brains of our ancestors (hominins) did not grow much for a few million years after the split from chimpanzees. However, the hominin brain expanded dramatically, from about 350 grams to 1,300-1,400 grams, during the last two to three million years. This represents unusually rapid growth in the geological time scale. Three million years is only 5 percent of the history of primate evolution, but human brains quadrupled in size during this relatively short period. The growth is largely due to the expansion of the neocortex, which takes up about 80 percent of the human brain by volume. Early mammals had little neocortex and about twenty distinct cortical areas, but present-day humans have about two hundred. This suggests that the rapid expansion of the neocortex was the main driving force for human cognitive specialization.

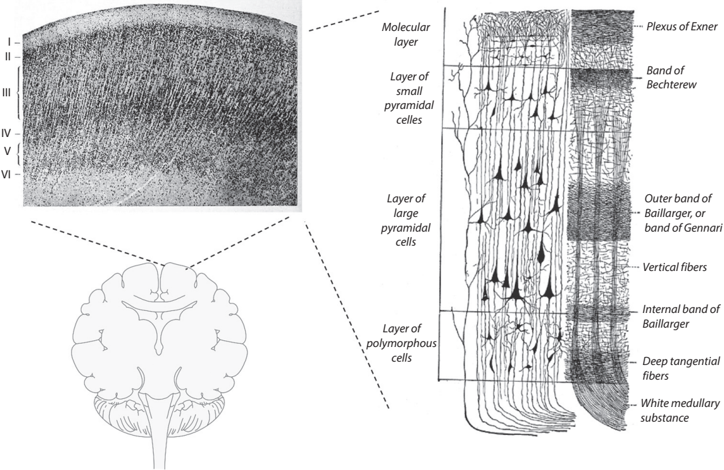

Even though the size of the neocortex varies widely across mammals, the basic circuit structure is largely similar across all areas of the mammalian neocortex (see fig. 8.6). This common neocortical circuit supports a plethora of brain functions such as seeing, listening, touch sensation, movement control, language comprehension, and reasoning. This suggests that the common circuit structure of the neocortex is an efficient, general-purpose processing module that can be used flexibly for a variety of purposes. In this regard, Bradley Schlaggar and Dennis O'Leary have shown that a strap of visual cortex (necessary for seeing) transplanted to the somatosensory cortex (necessary for touch sensation) in neonatal rats develops into a functional somatosensory cortex. Thus, although there remains a possibility the human neocortex has unique features, such as specialized neurons, that contribute to our advanced cognitive abilities, it is more likely that human neocortical evolution is driven by the duplication of existing circuits rather than the invention of new ones. Some genes regulate the activity of others. Some turn other genes on or off at specific times during brain development. Mutations in these genes could lead to dramatic changes in overall brain organization. Perhaps the evolutionary pressure during the last three million years favored the selection of mutations that expanded the neocortex by promoting the duplication of the common neocortical circuit.

FIGURE 8.6. The six-layer organization of the neocortex. The left top panel is reproduced from Korbinian Broadmann, 'File:Radial organization of tectogenetic layers in cerebral cortex, human fetus 8 months (K. Brodmann, 1909, p. 24, fig. 3).jpg,' Wikimedia Commons, updated January 23, 2020, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Radial_organization_of_tectogenetic_layers_in_cerebral_cortex,_human_fetus_8_months_(K._Brodmann,_1909,_p._24,_Fig._3).jpg; the right panel is reproduced from Henry V. Carter, 'File:Gray754.png,' Wikimedia Commons, updated January 23, 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gray754.png.

We should keep in mind, however, that a large brain comes with a cost. It gives you more processing power, but more energy is needed for its maintenance, which is problematic considering the brain is a metabolically expensive organ. According to an influential theory, the expensive tissue hypothesis, humans solved this problem by consuming a high-quality diet and thereby reducing the size of another energy-demanding organ, the gut. Many scientists agree that a high-quality diet or increased foraging efficiency probably helped the brain grow larger but disagree on how exactly this was achieved. According to an appealing hypothesis, the use of fire (i.e., cooking) increased the available caloric content in the food. However, the brain grew larger steadily in the hominin lineage over the last three million years or so, whereas the earliest available evidence for the use of fire dates back only one million years. Also, it is unclear whether cooking dramatically enhances the caloric availability of meat. Thus, the exact driving force for the expansion of the neocortex in the hominin lineage remains to be clarified.

HIPPOCAMPUS-NEOCORTEX DIALOGUE

The hippocampus and neocortex do not work independently but interact closely. The hippocampus is among the highest-order association cortices located far away from primary sensory and motor cortices. It interacts with the outside world primarily via its interactions with the neocortex. Hence, the content of memory and imagination the hippocampus deals with must be dictated by the information the neocortex provides. It is then plausible that the expansion of the neocortex advanced cognitive capability so that humans can imagine in spatial and nonspatial domains, including those dealing with high-level abstract concepts.

The following is a summary of my thoughts about how humans have acquired the capability to imagine freely using high-level abstract concepts. The imagination function of the hippocampus, i.e., the simulation-selection function, has evolved in land-navigating mammals to meet the need to represent optimal navigation routes between two arbitrary points in an area. The content of imagination then expanded from spatial trajectories to general episodes as the neocortex expanded. In particular, the explosive expansion of the neocortex has allowed the human brain to think and imagine using high-level abstract concepts (symbolic thinking). This has led to cultural and technological innovations including the organization of big societies. One highlight of brain evolution for abstract thinking would be its linguistic capacity. Language allows humans to communicate abstract ideas such as theories and feelings. Written languages, in particular, accelerated innovation by facilitating knowledge accumulation (see fig. 0.1). These consequences of high-level abstract thinking probably acted synergistically to accelerate innovations leading to human civilizations that are unprecedented in the history of life on earth.

To summarize, human innovation is probably an outcome of acquiring the capability for high-level abstraction due to the expansion of the neocortex. Adding this capability to the already existing imagination function, which is common to all mammals, allowed humans to be truly innovative. But which aspect of the neocortical expansion is crucial for high-level abstraction? This issue will be explored in the following chapters.