Chapter Seven

THE EVOLUTION OF IMAGINATION

Biological phenomena can be explained by proximal as well as ultimate causes. Proximal explanations concern underlying biological mechanisms, whereas ultimate explanations concern evolutionary origins and functional utilities. For instance, why do we get thirsty after eating salty food? One possible answer could be that a high salt intake increases blood osmolality, which is detected by osmolality sensors in the blood vessels that then activate the neural circuit that triggers water-seeking behavior (proximal cause). Another possible response could be that the biological machinery that detects and lowers high salt concentration has evolved because it is necessary for survival (ultimate cause). Our explanations of the simulation-selection model so far have focused on the proximal cause-the neural mechanisms of simulation-selection. What then is the ultimate explanation for the simulation-selection function of the hippocampus? Why has it evolved to perform simulation-selection? In this chapter, we will try to find an answer to this question by comparing the anatomy and physiology of the hippocampus across different animal species.

MAMMALIAN VERSUS AVIAN HIPPOCAMPUS

To recapitulate, replays found in the rat hippocampus suggest that it simulates diverse spatial trajectories during rest and sleep. Additionally, value-dependent activity of CA1 neurons suggests that CA3-generated spatial trajectories are selected in CA1 according to their associated values. Together, these findings suggest that the rat's hippocampus performs simulation-selection of diverse spatial trajectories, both experienced and unexperienced, during rest and sleep so that the rat can choose the optimal spatial trajectory between two arbitrary locations in the future.

What then is the ultimate cause of simulation-selection? My first question regarding this issue was whether the avian hippocampus also performs simulation-selection. This is because the bird, which can fly, may not need to exert effort to prepare for potential spatial trajectories in advance. The bird may travel directly 'as the crow flies' from its current position to its destination.

Unfortunately, there are few studies on the bird hippocampus compared to many on the rodent hippocampus. The most popular animal models for the hippocampus are rats and mice. Using the same animal model allows researchers to compare results from different studies, which facilitates a more complete understanding of a biological phenomenon or function of interest. Moreover, because evolution is generally a process of modifying existing biological machinery rather than inventing something entirely new from scratch, findings from one animal species are likely to be applicable to another. For example, biological functions of a specific gene in the fruit fly, a widely used animal model in biology, are often directly related to human genetic diseases. However, there is also a need for comparative studies, which allow us to understand how general a particular biological mechanism is across species and how it varies according to the species' ecological needs.

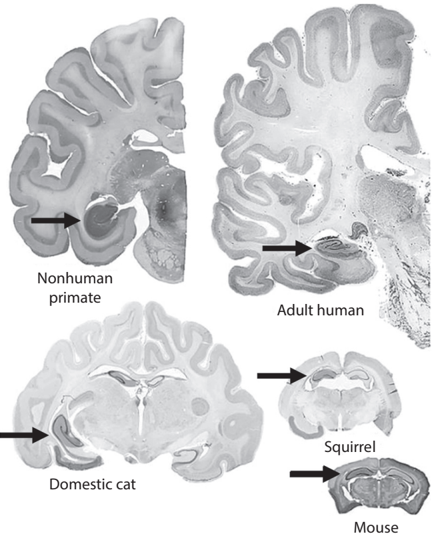

The structure of the hippocampus is surprisingly similar across different species of mammals, including humans. As shown by the brain cross sections of several mammalian species (see fig. 7.1), all mammalian hippocampi have similar gross anatomical structures with clearly distinguishable dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1. In contrast, as shown by brain cross sections of nonmammalian vertebrates (fish, reptile, and bird; see fig. 7.2), these animal species do not have clearly defined hippocampal subregions that correspond to the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 of the mammalian hippocampus. Anatomical studies have identified additional outstanding differences between the mammalian and avian hippocampus.

Mammals and birds, warm-blooded vertebrates, have far better spatial memory capacity compared to cold-blooded vertebrates (fish, amphibians, and reptiles). This may be quite ironic considering that calling someone a 'birdbrain' is considered an insult. In fact, many food-caching bird species have surprisingly superb spatial memory. Of a total of about 170 bird families,

FIGURE 7.1. Brain cross sections of several mammalian species. Hippocampal cross sections (indicated by arrows) show clearly distinguishable dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 in all species. Figure adapted from Jaafar Basma et al., 'The Evolutionary Development of the Brain as It Pertains to Neurosurgery,' Cureus 12, no. 1 (January 2020): e6748 (CC BY).

FIGURE 7.2. Brain cross sections of the goldfish, iguana, pigeon, and rat. The distinct cross-sectional structure of the mammalian hippocampus (arrow) is not shown in nonmammalian species (courtesy of Verner Bingman).

12 store food. For example, Clark's nutcrackers cache food, such as pine nuts, at thousands of locations and retrieve most of them in the winter. Because these locations become snow-covered in the winter, they must remember them on a spatial map of the food-caching area rather than remembering local features unique to each spot. Although the hippocampus oversees spatial memory in both mammals and birds, the mammalian and avian hippocampi differ drastically in their anatomical structures. This tells us that the way the hippocampus handles spatial information may differ drastically between the two groups.

PLACE CELLS IN PIGEONS

A team led by Verner Bingman at Bowling Green University in Ohio implanted microelectrodes in the pigeon hippocampus to examine spatial firing of avian hippocampal neurons. Due to technical issues, they recorded neural activity while the pigeon was walking rather than flying. Nevertheless, their studies provided rare and valuable data on spatial firing of hippocampal neurons. Does the pigeon hippocampus have place cells like the mammalian hippocampus does? The short answer is no. They trained pigeons to walk around in a plus maze to obtain food at the end of each arm. Interestingly, spatial activity patterns differed between the left and right hippocampi. Some neurons in the right hippocampus were active preferentially at many rewarding locations (known as goal cells) and some in the left hippocampus were active preferentially along the paths connecting two rewarding locations (path cells). This suggests that the pigeon hippocampus may only be concerned with the final target locations (i.e., rewarding locations) and the direct paths between them.

Another interesting finding from this research is that these spatial firing patterns diminish greatly if food rewards are scattered randomly in the maze. By contrast, rat hippocampal neurons show place-specific firing regardless of whether food rewards are scattered randomly or provided only at specific locations. These findings further indicate the difference between mammals and birds in the way the hippocampus processes and represents spatial information.

We can generate an infinite number of spatial trajectories by sequentially arranging place cells found in the rodent hippocampus. In contrast, it would be difficult to construct spatial trajectories based on the sequential firing of spatial neurons found in the pigeon's hippocampus. This casts a doubt on the implementation of simulation-selection in the pigeon's hippocampus.

EVOLUTION OF SIMULATION-SELECTION

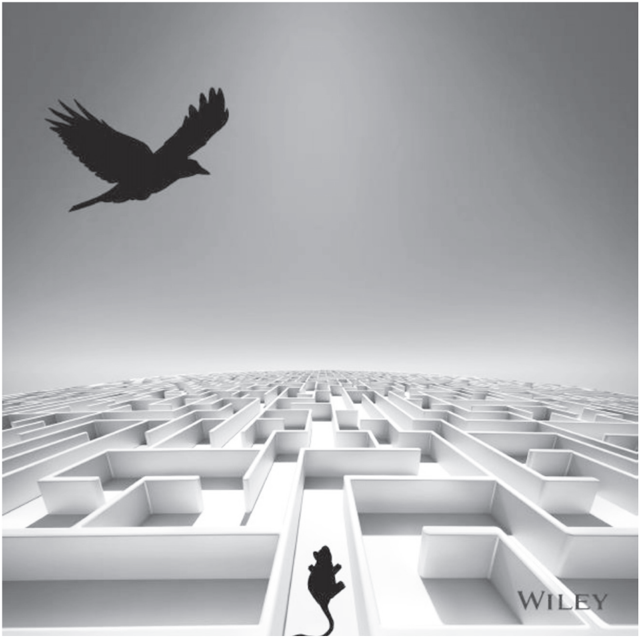

Figure 7.3 illustrates the key point of our proposal that the simulation-selection function of the hippocampus has evolved in land-navigating mammals because they need to choose optimal trajectories between two arbitrary locations. This need, however, does not apply to birds; they can fly directly to a target location. Land-navigating animals often face obstacles, such as rivers, trees, and rocks, that block the straight path toward a target location. They, therefore, need to remember trajectories that get around these obstacles to get to a target location in an efficient manner. However, it would require too much time and effort to learn all the optimal trajectories

FIGURE 7.3. Goal-oriented navigation in mammals and birds. Land-navigating mammals, but not birds, need to remember spatial trajectories. Figure reproduced with permission from Min W. Jung et al., 'Cover image,' Hippocampus 28, no. 12 (December 2018).

between two arbitrary locations in each environment by experience. One way to resolve this dilemma would be to learn optimal trajectories without actual navigation, i.e., performing simulation-selection. That would explain why simulation-selection may have evolved in land-navigating mammals but not in birds.

One might argue that it would be more efficient to compute the optimal trajectory as necessary rather than spending time and energy in advance to figure out an enormous number of trajectories that may or may not be used in the future. Such a strategy, however, may be fatal in emergency situations, even though it would be efficient in terms of energy expenditure. For instance, let's assume that you are a rabbit grazing on a field away from your burrow. When you realize that a fox is charging toward you, you must run back home using the shortest available route. It may take too long to compute the optimal route in such a circumstance. A delay of one or two seconds may cost you your life. Advanced simulation-selection would prepare you to identify optimal navigational routes between an arbitrary starting location and your burrow. Hence, even though it may be time- and energy-consuming, it may be advantageous for survival to represent optimal trajectories from arbitrary starting locations to a few target locations in each environment. Furthermore, the environment may change dynamically. Lush and dense grass that used to block your passage may disappear in the winter, or a deep-water pit may appear on your favorite route after a heavy rain. It would then be advantageous for survival to keep updating your optimal strategies. Otherwise, a land-navigating species may not be able to survive in the long run.

Assuming so, when would be the best time to perform simulation-selection? Obviously, not when you are being chased by a predator. It would be more reasonable to perform it during rest or sleep when you don't need to pay attention to the outside world. This may be why the hippocampus, as a part of the default mode network, is active during resting states. Considering that the hippocampus is an evolutionarily old structure, and that it is globally synchronized with the rest of the brain during sharp-wave ripples, the process of simulation-selection may have been a crucial factor in the evolution of the default mode network. As we examined in chapter 1, the default mode network is active in association with various types of internal mentation, such as autobiographical memory recollection, daydreaming, moral decision-making, theory of mind, and divergent thinking; simulation is thought to underlie all these internal mentation processes.

WHALES AND BATS

Considering my argument that the simulation-selection function of the hippocampus may have evolved in mammals because of the unique navigational need of land mammals, it would be interesting to examine the hippocampus of the mammals that abandoned ground navigation. Cetaceans, such as whales, went back to the sea and bats acquired wings that enable them to fly. These animals may have lower demands to store a large number of potential navigation trajectories compared to land-navigating mammals. How developed is the spatial firing of hippocampal neurons in cetaceans? To my knowledge, no one has recorded any data on that. But there are studies examining the anatomy of the whale hippocampus. These studies found that its relative size is much smaller compared to other mammals, suggesting a degeneration of the whale hippocampus during evolution. This finding supports the possibility that the hippocampus of land-navigating mammals has evolved to find and remember optimal spatial trajectories between two arbitrary locations that can be used in the future. In comparison, the whale would rarely face obstacles during travel.

On the other hand, bats have well-developed hippocampi. Furthermore, physiological studies have found three-dimensional place cells (or space cells) in their hippocampi. This does not support our ultimate explanation for the simulation-selection function of the hippocampus. Why do bats have clear place cells but pigeons don't, even though they can fly? It may be that the bat's lifestyle differs from the pigeon's so that it is advantageous for bats to figure out potential navigation trajectories. For example, bats often reside in enclosed spaces like caves and knowing diverse navigation trajectories may be adaptive in such an environment. Bats are also known to be more specialized in maneuvering than flying compared to birds. Hence, navigation behaviors of bats may differ substantially from those of birds, suggesting that the simulation-selection function of the mammalian hippocampus has been preserved in bats during evolution.

Another possibility is a dissociation between the cognitive map and trajectory representations. Hippocampal replays of spatial trajectories during rest and sleep are yet to be found in the bat. Hence, it is possible that the bat hippocampus represents cognitive maps of the external world, which is manifested by clear place cells, but does not perform simulation-selection. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that place cells of the bat's hippocampus may serve functions other than cognitive map or trajectory representation.

A transformation of an existing function to another happens commonly during evolution. For example, auditory ossicles (tiny bones in the middle ear) have evolved to serve an auditory function (amplifying sound signals) from a jawbone that serves a feeding function. The exact functions of place cells found in the bat hippocampus remain to be clarified.

TUFTED TITMOUSE, A FOOD-CACHING BIRD

In contrast to bats and whales, some birds need particularly superb spatial memory for survival. Food-caching birds, such as the Clark's nutcrackers mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, store food at thousands of places in the fall and retrieve it successfully in the winter. An issue related to retrieving cached food from multiple locations is the sequence of visiting the locations. This is a well-known problem in artificial intelligence: the traveling salesman's problem, where the number of possible visiting sequences increases exponentially as the number of locations increases. It is then conceivable that evolutionary pressure might have implemented neural machinery to compute optimal visiting sequences in food-caching birds. In this regard, a study on the marsh tit, another food-caching bird species, has shown that it retrieves cached food in the sequence it is stored rather than randomly. This finding suggests that the marsh tit retrieves cached food by considering not only stored locations but also navigation sequences. How do the birds solve these problems?

Even though we do not yet know, a recent study provides a clue to this issue. A team led by Dmitriy Aronov at Columbia University compared hippocampal neural activity between two bird species: food-caching and non-food-caching. Hippocampal neurons in the food-caching tufted titmouse showed place-specific activity, which is comparable to place-cell activity in the rat hippocampus. In contrast, the zebra finch, a species that does not store food, had much weaker place-specific hippocampal neuron activity. An independent study also failed to find place cells in the quail's hippocampus (quails can fly even though they prefer to walk on the ground). These findings suggest that the titmouse's hippocampus may have evolved to precisely represent the layout of the external space to meet the ecological demand (food caching) in a way similar to the spatial representation in the mammalian hippocampus. Considering that birds and mammals are separated by 310 million years of evolution, and that clear place cells are seldom found in non-food-caching birds (the pigeon, zebra finch, and quail), this

is more likely to be an example of convergent evolution (wherein similar traits evolve independently) rather than a deeply preserved evolutionary trait. In other words, the titmouse's hippocampus has probably evolved to show place-specific activity independent of the evolution of the mammalian hippocampus.

Notably, for the first time in birds, Aronov's team detected sharp-wave ripples in both species (the tufted titmouse and zebra finch) during deep sleep. What are the functions of sharp-wave ripples in birds? Would the place cells of the titmouse's hippocampus fire along spatial trajectories during sleep like mammalian place cells, potentially aiding the bird in retrieving cached food in optimal visiting sequences? Then how would hippocampal neurons of the zebra finch fire during sharp-wave ripples? We currently have no answers to these questions. We cannot exclude the possibility that the titmouse's hippocampus has evolved to perform simulation-selection during sleep by taking advantage of existing sharp-wave ripples. If so, this could be an example of the convergent evolution of a highly complicated mental process.

EVOLUTION AND LIFE DIVERSITY

To summarize, it is not entirely clear how the hippocampus of two evolutionarily distant animal groups, birds and mammals, has evolved to handle spatial information in the process of adapting to diverse ecological environments. Evolution is not one-way traffic-it promotes changes in whatever direction that helps a species better survive. A species may lose an existing function or acquire a new one in this process. The history of such ongoing processes represents the current diversity of life. There are about thirty-five phyla in the animal kingdom. We belong to the phylum Chordata, which consists of three subphyla. Vertebrata is one. Of the remaining two, Urochordata is phylogenetically closer to vertebrates. Thus, Urochordata is the closest neighbor to vertebrates in terms of evolutionary history.

Figure 7.4 shows typical Urochordata, marine tunicates (sea squirts). Surprisingly, they are sessile (fixed in one place) and appear closer to sea anemones, animals located way lower on the phylogenetic tree than vertebrates. They do show all the characteristics of Chordata (i.e., notochord, dorsal nerve cord, gill slits, and postnatal tail) during development but lose these characteristics and motility during development. The case of Urochordata illustrates how far and diversely biological traits can change during evolution.

THE NEURAL SYMPHONY OF IMAGINATION

FIGURE 7.4. Marine tunicates. Figure reproduced from Nick Hobgood, 'Tunicates,' Wikimedia Commons, updated April 20, 2006, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4590928 (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Perhaps the simulation-selection function for potential spatial trajectories may have been lost or acquired during evolution. So far, our studies on hippocampal spatial representation and replays are limited to a handful of animal species. The picture will become clearer as we expand our hippocampal research to additional animal species.