Chapter Five

VALUE-BASED DECISION-MAKING

In this chapter, we will examine hippocampal value processing as the last piece of the puzzle before building a model of hippocampal neural circuit processes underlying memory and imagination. So how does value processing relate to hippocampal roles in memory and imagination? This will become clear in chapter 6 when we examine a simulation-selection model of the hippocampus. As a brief answer in advance, the model proposes that CA3 generates diverse activity sequences by self-excitation for both experienced and unexperienced events, and CA1 selects high-value activity sequences among them so that we can make better choices in the future. According to this model, the hippocampus is a device used to plan for future events rather than simply remembering what happened in the past. This model is grounded on the finding that the CA1 region of the hippocampus processes and represents value signals. We will examine this issue in detail in this chapter and, in doing so, briefly overview reinforcement learning and decision neuroscience.

VALUE, UTILITY, AND VALUE FUNCTION

Much progress has been made over the last twenty years in understanding the neural basis of value-based decision-making. A central assumption in studying the topic is that humans and animals make choices by representing values for potential choices. In the field of decision neuroscience, value

refers to a long-term expected return. A closely related concept in economics is utility , which refers to the usefulness or enjoyment one can get from consuming a product or service. Suppose you need a smartphone, and you are considering two specific models with similar prices: an Apple iPhone and a Samsung Galaxy. The amount of subjective satisfaction one can get from each smartphone will vary from person to person. The iPhone may have a larger utility for you than the Galaxy phone-or perhaps the other way around. You will likely purchase the one with the largest utility. The current mainstream economics, neoclassical economics, is based on the assumption that people ( Homo economicus ) make choices to maximize their utility.

The idea of value in decision neuroscience is referred to as value function in reinforcement learning, which is a branch of artificial intelligence. Why is this branch of artificial intelligence known as reinforcement learning ? Economics tries to explain and predict economic issues and problems by assuming that consumers and firms try to maximize their utility based on full and relevant information about their decisions. In contrast, reinforcement learning focuses on how a decision-maker finds precise value functions and an optimal choice strategy while interacting with an uncertain and dynamic environment. In other words, reinforcement learning is interested in the process of learning to approximate true value functions and finding an optimal choice strategy for maximizing long-term returns. Reinforcement learning laid the foundation for modern decision neuroscience by providing the major theoretical framework for neuroscientific investigation of decision-making.

REWARD PREDICTION ERROR

How does the brain process and represent value? It was not until the 2000s that this topic became popular among neuroscientists. Before this, neuroscientists tended to treat the brain like a computational device, focusing on the computational processes behind sensory processing and behavioral control. Few neuroscientists were interested in the neural process behind decisionmaking based on subjective values, such as choosing between a cappuccino and a latte, which would vary according to personal taste. In other words, neuroscientists used to be interested in how the brain processes sensory information and controls behavior rather than why the brain chooses one behavior over others. A dramatic change in this trend was triggered by a theoretical paper on dopamine neurons that was published in 1997. /uniF6DC

To get a clearer sense of the impact of this paper, we have to understand what reward prediction error is. As mentioned earlier, reinforcement learning deals with the process of finding precise value functions while interacting with an uncertain and dynamic environment. How? The simplest means would be through trial and error; you update your current value functions (expected rewards) according to the outcomes of your choices (actual rewards). As you iterate this process many times, your subjective value functions will converge to true value functions.

Suppose there are five restaurants to choose from for your lunch. Your value functions for them (the subjective satisfaction you can get from each restaurant) would be similar at the outset, but they will soon diverge as you visit them multiple times over a period. You increase your value function for a particular restaurant if a meal there was better than you expected and, conversely, decrease your value function if a meal was worse. This way, as you repeat your visits to these restaurants, your value functions for them will become closer to the true value functions. The world is not static, however. In our example, a particular restaurant may come up with a new menu or hire a new chef, which will make your current value function deviate from the true value function for the restaurant. Even so, if you update your value function every time you visit the restaurant, your value function will eventually catch up with the changes and approximate the new, true value function.

As you can see from this example, a key component for reinforcement learning is the difference between the actual and expected rewards (the reward prediction error). You increase your value function for a particular choice if the outcome is better than your current value function (when your actual reward is better than your expected reward, it's a positive reward prediction error). Conversely, you decrease your value function for that choice if the outcome is worse than your current value function (when your actual reward is worse than your expected reward, it's a negative reward prediction error). Of course, the value function is not modified if the actual and expected rewards are equal. This way, reinforcement learning can approximate true value functions in an uncertain and dynamic environment.

In their 1997 paper, Wolfram Schultz, Peter Dayan, and Reid Montague showed that midbrain dopamine neurons signal the reward prediction error. These neurons, which project to widespread regions of the brain, play /uniF63A important roles in voluntary movements and reward processing. Abnormality in the dopaminergic neural system is associated with diverse neurological and mental disorders such as schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease,

and addiction. As can be predicted from their roles in reward processing and addiction, some midbrain dopamine neurons elevate their activity in response to reward delivery and reward-predicting stimuli. /uniF63B The researchers extended this finding by showing that some midbrain dopamine neurons are only responsive to an unexpected reward. Their activity is correlated with the difference between the actual and expected rewards rather than a reward per se.

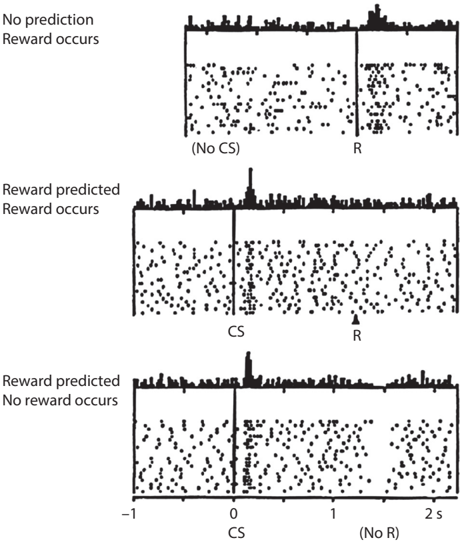

Figure 5.1 shows the spiking activity of a sample dopamine neuron recorded from a monkey. In the initial phase, a reward (juice) was given

FIGURE 5.1. The activity of a sample dopamine neuron recorded from a monkey. This neuron increased activity when juice was given in the absence of a predicting stimulus (top row; R represents reward delivery). After pairing a sound cue (conditioned stimulus or CS) and juice delivery multiple times (the sound cue always preceded juice delivery), the dopamine neuron was not responsive to juice delivery anymore. The neuron was responsive to the sound cue (reward-predicting stimulus) instead (middle row). If juice delivery is omitted after the sound cue, dopamine neuronal activity is decreased at the time of expected juice delivery (bottom row). Thus, the activity of this neuron signals the difference between the actual and expected rewards (i.e., reward prediction error). Figure reproduced with permission from Wolfram Schultz, Peter Dayan, and P. Read Montague, 'A Neural Substrate of Prediction and Reward,' Science 275, no. 5306 (March 1997): 1594.

to the monkey sporadically so that the time of reward delivery could not be predicted. Per previous reports, this neuron elevated spiking activity in response to reward delivery (top row). In the next phase, reward delivery was always preceded by a sound cue one second before so that the time of reward delivery could be well predicted. At this phase, surprisingly, the dopamine neuron stopped elevating its activity in response to the juice delivery (middle row). In other words, this dopamine neuron did not respond to an expected reward. Furthermore, when juice delivery was omitted after the sound cue (i.e., expected reward is omitted), the dopamine neuron decreased its firing rate (bottom row). You can easily see that the magnitude of reward prediction error differs for the three conditions. Reward prediction error was positive when juice was delivered unexpectedly (sporadic reward delivery with no predicting stimulus; top row), zero when the same amount of juice was delivered as expected (reward delivery following the sound cue; middle row), and negative when juice was unexpectedly omitted (reward omission following the sound cue; bottom row). This and subsequent studies showed that dopamine neurons increase their activity if the actual reward is larger than expected and, on the contrary, decrease their activity if the actual reward is smaller than expected. This finding shows clearly that some midbrain dopamine neurons are responsive to reward prediction error-a key variable in reinforcement learning.

NEURAL REPRESENTATION OF VALUE

The finding that midbrain dopamine neurons convey reward prediction error signals suggests that the brain might represent values and update them according to actual choice outcomes. The next critical issue would be whether the brain represents value, another key component of reinforcement learning. The answer to this question is clear. Subsequent studies found value-related signals in many different parts of the brain in rats, monkeys, and humans. Neurons in these areas of the brain change their activity according to the type, amount, and probability of a reward. /uniF63C Appendix 2 explains how scientists identify value-coding neurons with a specific example. These studies revealed that widespread regions of the brain represent reward prediction error and value, two critical elements of reinforcement learning. They also showed that choice behaviors of animals and humans are well accounted for by reinforcement learning algorithms in many behavioral settings.

The core idea of reinforcement learning is intuitive. You make choices according to your expectations and update your expectations according to actual outcomes. Your expectations will approach actual outcomes as you repeat this process, and your performance will improve accordingly. The findings of reward prediction error and value signals in the brain propelled further research on the neural basis of value-based decision-making. This line of research, decision neuroscience, is closely related to psychology, economics, and artificial intelligence. It is also called neuroeconomics since it studies the neural processes underlying economic decisions.

HIPPOCAMPUS AND VALUE

The hippocampus has long been considered a structure that represents cognitive signals, particularly spatial ones, rather than value signals; valuerelated information has been thought to be represented elsewhere in the brain. Recall the role of the hippocampus in declarative, but not procedural, memory (see chapter 1). Also, recall place cells and the role of the hippocampus in representing the spatial layout of the external environment (cognitive map; see chapter 3). Of course, it is well known that hippocampal neurons are responsive to reward (e.g., food) and punishment (e.g., an electric shock). However, the concepts of reward and value are not identical, even though they are related. Value is the final product of a cost-benefit analysis considering the type, amount, and probability of a reward along with the cost to obtain it. Value is the same concept as expected return in economics and finance, which is the profit an investor anticipates on a financial investment. Hippocampal responses to a reward are consistent with hippocampal value representation, but they may merely indicate the role of the hippocampus in representing experienced events (i.e., remembering the event of receiving a particular reward in a particular environment).

For these reasons, few scientists were interested in investigating value representation in the hippocampus. A growing body of findings indicates, however, that the hippocampus is among many brain areas involved in value representation. So far, value signals have been identified in the hippocampus of rats, monkeys, and humans. /uniF63D Below, I will summarize a series of findings using rats in my laboratory that indicated hippocampal representation of value and hippocampal involvement in value-based decision-making. My laboratory, like many others, focused on the frontal cortex and basal ganglia in the initial exploration of the brain's value processing because they are targets of dopamine neuronal projections and are strongly implicated in reward-oriented behavior. One clear conclusion of this endeavor was that value processing is a ubiquitous function of the brain; we found valueresponsive neurons in widespread areas of the rat brain. /uniF63E

Studies in monkeys and humans also indicated that widespread areas of the brain are involved in value processing. /uniF63F This suggests that value representation is an evolutionarily conserved function of the brain. It is often the case that the same function is found redundantly across many brain areas and sometimes across the entire body. For example, a biological clock is found in virtually all cells in our body, even though one master clock would be sufficient to control our circadian rhythms. Evolution is a process of /uniF640 tinkering (modifying and improving an already existing system) rather than inventing an entirely new system from scratch. Hence, redundant functions are likely to be rooted deeply in evolution. As a rule, the more redundant a given function is, the more likely it is essential for survival and reproduction. Representing values of potential choices and making optimal choices based on them would be critical for survival and reproduction. It may not then be surprising to find value signals all over the brain.

As we found value-responsive neurons in various regions of the brain, we got curious about the possibility of value representation in the hippocampus. Because the hippocampus is an evolutionarily old structure, and because value-based decision-making would be critical for survival, we thought that the hippocampus might as well be involved in value processing. Hyunjung Lee, then a graduate student, investigated this matter by implanting microelectrodes in the rat hippocampus.

VALUE REPRESENTATION IN CA1

Considering the traditional view that the hippocampus is specialized in representing spatial and cognitive signals, we initially thought that hippocampal value signals, if present, would be stronger in the output structures of the hippocampus rather than in the hippocampus itself. We therefore decided to examine neural activity in CA1, which is the final stage of the trisynaptic circuit, and the subiculum, which relays CA1 outputs to other cortical areas (see fig. 4.1). Our cautious prediction was that value signals would be found in the subiculum but not in CA1; or, if both areas convey value signals, the signals would be stronger in the subiculum than in CA1. This prediction turned out to be wrong.

Hyunjung trained thirsty rats to choose between two targets that delivered a water reward with different probabilities. The reward probabilities were not static but unpredictably changed over time. Thus, the rats had to decide which target to choose in a dynamic and uncertain environment. To maximize water intake in this circumstance, the rats had to figure out the reward probabilities of the two targets (values for the two target choices) based on the history of past choices and their outcomes and distribute their choices over two targets considering their relative values (i.e., reward probabilities). This process is well captured by reinforcement learning. Indeed, the rat's choice behavior in this task was well predicted by a simple reinforcement learning model, suggesting that the rats estimated and updated values for the two targets based on the history of past choices and their outcomes. Hyunjung estimated trial-by-trial values for the two targets using a reinforcement learning model and tested whether there are neurons whose trial-by-trial activity is correlated with value. See appendix 2 for a more detailed explanation of the procedure for finding value-coding neurons.

To our surprise, strong value signals were found in CA1 but not in the subiculum. /uniF641 A large fraction of CA1 neurons, but only a small fraction of subiculum neurons, were responsive to value (a sample of value-coding CA1 neurons is shown in appendix 2). We were surprised but at the same time excited by this unexpected finding. A perplexing yet thrilling moment for a scientist occurs when facing an unexpected result. I began my neuroscience career in 1986 as a graduate student at the University of California, Irvine. I had thought about neural circuit processes underlying hippocampal functions for a long time but could not come up with a satisfactory answer, especially regarding the role of CA1 in hippocampal functioning. But this unexpected finding-that CA1 represents strong value signals-provided a breakthrough; we were able to devise a new model of the hippocampus, which I think captures the essence of hippocampal circuit operations, based on this finding. This model will be elaborated on in chapter 6.

VALUE REPRESENTATION IN CA3

We were shocked by the finding that CA1, rather than the subiculum, represents strong value signals. Why does the hippocampus, which is known to be primarily concerned with cognitive information, represent value signals? How is hippocampal cognitive signal processing affected by value signals?

What is the role of value signals in the functioning of the hippocampus? As a step to investigate these matters, we examined whether CA3, the major input structure of CA1, also represents value signals. Sung-Hyun Lee, then a graduate student, compared the value signals of CA3 and CA1. /uniF6DC/uniF639 The conclusion was clear. Value signals were much weaker in CA3 than in CA1. This result indicates that CA3 is not the source of CA1 value signals. Also, the fact that value signals are strong in CA1 but weak in its main input (CA3) and output (subiculum) structures suggests that value representation may be a special characteristic of CA1 among the hippocampal subregions.

WHAT IF CA1 IS INACTIVATED?

The results so far are outcomes of correlational studies that show spiking activities of many CA1 neurons are correlated with values of two targets. In general, correlational and interventional studies complement each other. We activate or suppress a certain part of the brain and examine its consequences on behavior in an interventional study. We can conclude with some confidence that a certain brain structure plays an essential role in a certain function when both correlational and interventional approaches yield converging results. In our case, that CA1 processes strong value signals (correlational approach) and CA1 inactivation impairs value-based decisionmaking (interventional approach) would make a strong case for the involvement of CA1 in value processing. Of course, correlational and interventional approaches do not always yield converging results. Even though strong neural signals related to a certain function were found in a brain structure, its inactivation may have no behavioral consequence. This is because a given function may be served redundantly by multiple brain structures.

With this background, we examined the behavioral consequences of inactivating the CA1 of mice. This work was done by Yeongseok Jeong, then a graduate student. In fact, I was somewhat reluctant to perform this study. As mentioned earlier, value signals are found in widespread areas of the brain. Moreover, numerous studies indicated the importance of the frontal cortex and basal ganglia in value-based decision-making. Thus, it seemed that hippocampus-inactivated animals may well rely on these neural systems for value-based decision-making. Moreover, many studies indicated the role of the hippocampus in the rapid encoding of declarative memory (see chapter 1) rather than incremental value learning, which was believed to be mediated by the basal ganglia. /uniF6DC/uniF6DC For these reasons, I predicted that

CA1 inactivation would minimally affect a rat's choice behavior in tasks that require trial-by-trial adjustments of values according to trial outcomes. This experiment was nevertheless necessary to follow up on the finding that CA1 represents strong value signals. This is a type of study a graduate student may not be very enthusiastic about. It is generally difficult to publish a negative finding (i.e., CA1 inactivation does not affect behavior). In our case, if we found no effect of CA1 inactivation on the animal's choice behavior, it would be difficult to tell whether the absence of inactivation effect was because CA1 is dispensable for value-based decision-making or because CA1 was insufficiently inactivated. Thankfully, even with this caveat, Y eongseok agreed to perform this study with little hesitation.

My prediction turned out to be wrong one more time. Yeongseok found that CA1 inactivation alters the mice's choice behavior so that they were less successful in obtaining water. /uniF6DC/uniF63A He used a technique known as chemogenetics to selectively inactivate different subregions of the hippocampus (CA1, CA2, CA3, and dentate gyrus) and examined the mice's choice behavior. /uniF6DC/uniF63B He then used a reinforcement learning model to study which aspect of valuebased decision-making was affected. He found that CA1 inactivation impairs value learning; the process of value updating based on choice outcomes (i.e., value updating based on reward prediction error) was compromised in CA1inactivated mice. By contrast, the inactivation of CA2, CA3, or dentate gyrus had no significant effect on the mice's choice behavior whatsoever. I was once again surprised by this finding. In my estimate, the chance of getting a positive finding was well below 50 percent. We had some trouble publishing this finding in a peer-reviewed journal. This was probably because of the long-standing view in the field that the hippocampus is important for rapid encoding of facts and events but not for gradual value learning.

CA1: A VALUE SPECIALIST

Let's summarize the findings in rats and mice. First, CA1 represents strong value signals, but its main input and output structures, CA3 and subiculum, respectively, represent values only weakly. Second, CA1 inactivation impairs value-based decision-making, but dentate gyrus, CA2, or CA3 inactivation had no significant effect on the animal's choice behavior. The message of these findings is clear. Value representation, as a unique characteristic of CA1 among hippocampal subregions, is likely to play a crucial role in CA1 functioning.

The hippocampus has traditionally been thought to process cognitive information, especially spatial information. From this standpoint, the function of CA1 has been puzzling because spatial firing patterns are similar between CA3 and CA1 neurons. Of course, subtle differences are found between CA3 and CA1 place-cell characteristics, but overall, they are quite similar. As to the functional differentiation between CA3 and CA1, do both CA3 and CA1 represent spatial information (cognitive maps)? If so, why do we need both CA3 and CA1? Isn't CA3 alone sufficient to represent external spatial information? There exist numerous theories on this issue, but, to me, none is persuasive. Our findings provide a new perspective on this longstanding issue. That CA1 is a value specialist among all hippocampal subregions provides a clue to understanding the functional role of CA1.

Up to now, we have examined pieces of the puzzle to understand how the hippocampal neural network supports memory and imagination. In chapter 6, we will try to put them together to see the overall puzzle.