Chapter Four

NEURAL CIRCUITS OF THE HIPPOCAMPUS

In previous chapters, we examined the functional roles of the hippocampus, i.e., what the hippocampus does. In this chapter, we will explore how the hippocampus does what it does. Many neuroscientists are interested in a mechanistic understanding of brain functions in terms of neural circuit processes. Suppose you want to understand the mechanics of how a car uses gasoline when driving. A simple way to explain this would be that gasoline's combustive force allows the car to be driven. Would you be satisfied with this answer? Probably not. A more satisfactory answer would be that gasoline explosions inside a combustion engine force a piston to move up and down, a crankshaft translates the piston's linear motion into rotational motion, and the rotational power of the crankshaft turns the wheels of the vehicle. Similarly, neuroscientists are not satisfied with just knowing that the hippocampus serves memory and imagination functions. They want to go further to understand how the hippocampus serves these functions in terms of underlying neural circuit processes.

Thanks to the rapid technological advances of the past few decades, neuroscientists are now equipped with powerful tools to directly study the neural circuit processes underlying higher-order cognitive functions, such as decision-making and imagination. And considering the accelerating progress of technology, scientists are cautiously optimistic about the future of this endeavor-explaining higher-order cognitive functions in terms of underlying neural circuit processes (known as mechanistic cognitive neuroscience).

In this chapter, to build a foundation for exploring the neural circuit processes underlying memory and imagination functions of the hippocampus, we will examine the anatomy of the hippocampus along with a classic theory for the functioning of the hippocampal neural network.

TRISYNAPTIC CIRCUIT

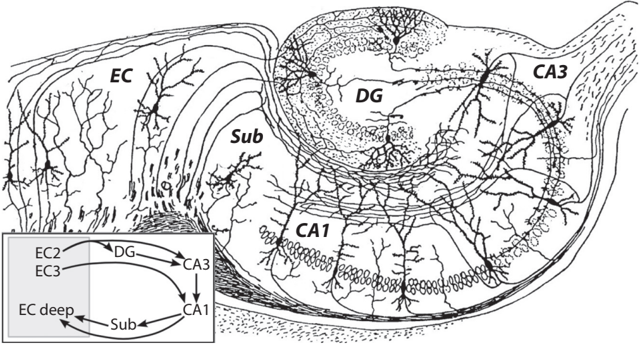

The hippocampus is a sausage-shaped structure located deep in the medial temporal lobe. Figure 4.1 shows a hand drawing of the hippocampal crosssection by Santiago Ramón Cajal, a Spanish neuroanatomist and a Nobel laureate (1909). The dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 are three major subregions of the hippocampus. The circuit that contains these structures (dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1) is known as the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit . CA stands for cornu Ammonis, named after the Egyptian deity Amun, who has the head of a ram. Neurons in the dentate gyrus project to CA3 and neurons in CA3 in turn project to CA1.

This circuit (dentate gyrus → CA3 → CA1) has long been considered the most prominent neural pathway of the hippocampus and, therefore, has been the main target of research on hippocampal memory encoding and

FIGURE 4.1. Santiago Ramon Cajal's hand drawing of the hippocampal cross-section. DG stands for dentate gyrus, Sub for subiculum, and EC for entorhinal cortex, which is the main gateway of the hippocampus. The inset shows a schematic of neural connections. EC2, EC3, and EC deep denote the entorhinal cortex's layer 2, layer 3, and deep layers, respectively. Panel from 'File:CajalHippocampus (modified).png,' Wikimedia Commons, updated April 19, 2008, https:/ /commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CajalHippocampus_(modified) .png (CC BY).

retrieval. Note, however, that there are alternative connection pathways in the hippocampus (see inset of fig. 4.1). Moreover, recent studies indicate that a relatively small structure, CA2, has its own functions, such as social recognition memory (remembering events related to conspecifics). /uniF6DC However, because there are relatively few studies on CA2 and CA2's contribution to overall hippocampal functions is unclear, we will not examine CA2 here. Also, for the sake of simplicity, we will focus only on CA3 and CA1, leaving out the dentate gyrus, because they appear to be the core structures directly related to imagination, the main topic of this book. Brief discussions on the role of the dentate gyrus can be found in chapter 6 and appendix 1.

CA3 NETWORK

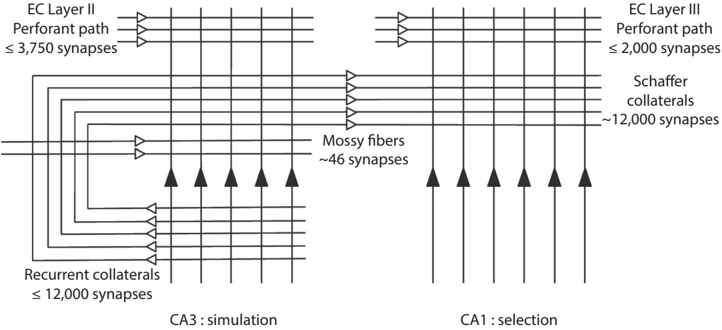

CA3 has long been at the center of the theoretical debate on the neural circuit processes that underpin hippocampal memory. It is also thought to be the central structure for the imagination function of the hippocampus. Why? Because CA3 neurons can excite each other. How? CA3 neurons not only project to other areas, such as CA1, but also back to themselves via massive recurrent collaterals , which are axon branches that ramify near the cell body (see fig. 4.2). Recurrent projections, which are commonly found

FIGURE 4.2. A schematic for CA3-CA1 neural circuits. Black triangles represent excitatory neurons and white triangles represent the projection directions of axons. EC stands for entorhinal cortex. Figure reproduced from Min W. Jung et al., 'Remembering Rewarding Futures: A Simulation-Selection Model of the Hippocampus,' Hippocampus 28, no. 12 (December 2018): 915 (CC BY).

in the cerebral cortex, allow internal interactions within a group of neurons. Such interactions enable a neural network to maintain and process information by internal dynamics in the absence of external input, a process thought to be essential for supporting higher-order cognitive functions of the cerebral cortex. Otherwise, a neural network will behave like a reflex machine responding simply to the presence of external input and be idle otherwise.

One defining characteristic of CA3 is an unusually large number of recurrent projections that connect its neurons. On average, one CA3 neuron receives about twelve thousand inputs from other CA3 neurons in the rat hippocampus. This amounts to three-quarters of all excitatory inputs a CA3 neuron receives (see fig. 4.2)! /uniF63A The sheer number of CA3 recurrent projections is indeed remarkable. What comes to your mind when you see such massive mutual connections? As you may have guessed, the CA3 neural network has a strong tendency for self-excitation. A side effect of such a neural network structure would be a tendency for a runaway excitation, i.e., seizures when network activity is not properly controlled. Epilepsy refers to a neurological disorder with repeated seizures. Considering the massive mutual connections among CA3 neurons, it is not surprising that temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common form of focal epilepsy. Henry Molaison (see chapter 1) suffered from such severe temporal lobe epilepsy that he underwent medial temporal lobe bisection.

CONTENT ADDRESSABLE MEMORY

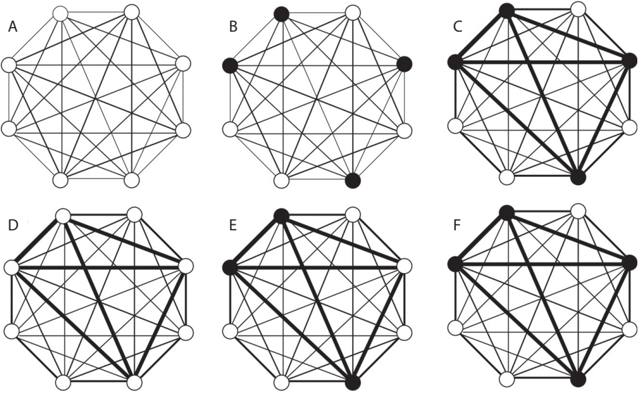

Seizures are outcomes of abnormal circuit operations. What then is the physiological function of the CA3 neural network? Currently, the most influential theory on this issue is the one proposed by David Marr in 1971. /uniF63B According to this theory, the CA3 neural network stores memories by changing the strengths of synaptic connections among CA3 neurons (i.e., by altering the synaptic efficacy of CA3 recurrent projections). More specifically, synaptic connections among CA3 neurons representing a certain experience are strengthened, forming a functional 'cell assembly' of CA3 neurons representing that experience. Later, if part of the functional assembly is activated, /uniF63C the rest of the CA3 neurons in the functional assembly are activated as well (because their connections are strengthened), therefore recovering the original activity pattern for the experience (memory retrieval). This process is explained schematically in figure 4.3.

FIGURE 4.3. Storage and retrieval of memory in a neural network. Schematics illustrate how memory is stored in and retrieved from an interconnected neural network. Open and closed circles represent inactive and active neurons, respectively. Lines represent bidirectional connections between two neurons with the thickness indicating connection strength. The eight neurons in each neural network are all connected by recurrent projections. Let's assume that the network experiences an event, X. (A) shows the state of the network before experiencing X, and (B) occurs while experiencing X. We assume here that simultaneous activation of the four neurons (filled circles) corresponds to the perception of X. (C) shows that connections among simultaneously active neurons are strengthened to form a functional assembly. (D) occurs sometime after X. Although all neurons are inactive, enhanced connection strengths among the four neurons in the functional assembly persist, which is a long-lasting trace of memory. (E) shows a state of the network in response to a stimulus that is relevant to X. If the network did not experience X and no connection strength changes occurred, then the stimulus would be perceived as a new experience. (F) However, because synaptic connections among the four neurons of the functional assembly have been enhanced, the activity of three neurons will drive the activity of the one remaining. This way, the original pattern is completed, and the original memory is retrieved.

Scientists generally believe that a neural network stores and retrieves information in this manner, which differs from the way digital computers store and retrieve information. A digital computer stores information (memory) at a given address (e.g., a certain physical location on a hard disk) and retrieves the stored information by reading out information from that address. In contrast, a neural network stores information in a distributed manner by changing connection strengths among active neurons, as shown in figure 4.3. The stored information is retrieved by recovering the original activity pattern from a partial activation, a process called pattern completion . In other words, partial activation of the stored memory is necessary to retrieve the original activity pattern. This type of memory is sometimes

FIGURE 4.4. Memory retrieval by pattern completion. We can recall a memory by completing an original pattern from an incomplete or degraded input.

called content-addressable memory in the sense that the content of a particular memory is used to retrieve the memory, such as the memory address of a digital computer.

A memory comes to our mind when we encounter a related sensory input or while thinking about things related to that memory. We recall memory based on neural activity related to the stored memory rather than by exploring a certain location of the brain (address) where the memory is stored. Figure 4.4 illustrates this point. Suppose you encoded visual information on someone's face as a memory. Then you can recall the face easily when given partial or degraded visual information about the face.

SEQUENCE MEMORY

Marr's theory was adopted and further developed by later scientists. The core idea, that the CA3 neural network stores memory by enhancing connection strengths among coactive CA3 neurons, has been highly influential for the last fifty years. However, Marr's theory deals with the storage of static patterns, not sequences. When we examined hippocampal replays in chapter 3, we saw that the hippocampus does not merely store snapshots of our experiences but also stores event sequences that unfold over time. In addition, we now know that the hippocampus is involved not only with memory but also with imagination. Marr's theory is limited in explaining these aspects of hippocampal functions.

The discovery of hippocampal replays sparked interest in the neural processes underlying the storage and retrieval of experienced event sequences (episodic memory) and the generation of unexperienced event sequences (imagination). Again, CA3 is at center stage in this line of research. Because CA3 neurons are interconnected by massive recurrent projections, partial activation of CA3 neurons may sequentially activate other CA3 neurons. Physiological studies also showed that sharp-wave ripples, during which most hippocampal replays are detected, are initiated in CA3. Therefore, /uniF63D there are good reasons to believe that CA3 plays a critical role in storing and retrieving experienced event sequences and in imagining unexperienced event sequences.

CA1 NETWORK

CA1, the final stage of the trisynaptic circuit, receives massive inputs from CA3 and sends outputs to surrounding areas of the hippocampus. In this sense, we may consider CA1 an output structure of the hippocampus. What then is the function of CA1? Even though numerous theories have been proposed regarding its role, empirical evidence is only tenuous, and nothing has been accepted as widely as Marr's theory on CA3. Anatomically, CA1 is different from CA3 in that it lacks strong recurrent projections; the major/uniF63E ity of CA1 neuronal axons are directed to the outside of the hippocampus. Thus, unlike CA3 neurons, CA1 neurons are likely to process information with little direct excitatory interaction among them. This suggests that neural network dynamics and functional roles of CA1 are likely to differ vastly from those of CA3.

You may then predict that neurophysiological characteristics, such as place-specific firing, would differ greatly between CA3 and CA1. Contrary to this prediction, scientists failed to find major neurophysiological differences between CA3 and CA1 neurons. Place cells are found in both CA3 and CA1 with largely similar characteristics. This suggests that the nature of processed information, particularly spatial information, is similar between CA3 and CA1. So why do two anatomically distinct structures process similar information? Why is CA1 even necessary if it processes similar information? We will examine this issue in detail in the next chapter. For now, my brief answer is that CA1 probably selects and reinforces high-value sequences generated by CA3.

I would like to show my respect to David Marr (1945-1980) before wrapping up this chapter. He made enormous contributions to the field of neuroscience. He proposed the first realistic neural network model for the hippocampus when our knowledge of the hippocampal neural networks was limited. More surprising is that his work on the hippocampus represents only a fraction of his contributions to neuroscience. He also proposed influential theories for the neocortex and cerebellum, and he is best known for his work on vision. Overall, Marr is considered a pioneer and founder of modern computational neuroscience. I think that hippocampal researchers can best show him respect by advancing his long-standing theory of the hippocampus. Perhaps all scientists, including him, would be happy to see their theories replaced by the next generation's work. This is how science advances.