Chapter Three

PLACE CELLS AND HIPPOCAMPAL REPLAY

Human studies have shown that the same brain structure (the hippocampus) is involved in both memory and imagination, which may explain why we sometimes form memories of events we have never experienced (false memories). In this chapter, we will examine studies using animal subjects that provided important insights into hippocampal neural processes underlying memory and imagination.

HUMAN STUDIES VERSUS ANIMAL STUDIES

Two lines of research-one using human subjects and the other using animal subjects, rodents in particular-have driven the advancement of our knowledge of the hippocampus. Human studies yield data that is directly relevant to our ultimate interest: the functions of the human hippocampus and their underlying neural processes. However, it is difficult to interrogate hippocampal neural processes directly in humans because invasive approaches, such as recording neuronal activity with a microelectrode, are not allowed in humans. Such invasive studies are performed only rarely in human patients, and usually before brain surgery, to locate the source of epileptic seizures.

Animal studies are advantageous in this respect because we can perform a diverse array of invasive experiments targeting the hippocampus. For example, we can implant microelectrodes in the hippocampus and monitor in real time the spiking activities of individual neurons in a freely behaving animal.

We can also manipulate the activity of neurons in the hippocampus, such as by silencing a particular group of neurons and examining its effects on animal behavior. Such animal studies provide valuable information to our ultimate interest-understanding the functions and neural processes of the human hippocampus-because this evolutionarily old structure is remarkably similar in many respects between humans and other mammals. Therefore, human and animal studies on the hippocampus are complementary.

Animal studies have taught us a great deal about how the hippocampus stores memories. For example, the discovery of long-lasting changes in synaptic efficacy (i.e., changes in connection strengths between neurons; synapses are the connections between neurons) has greatly advanced our understanding of the neural processes underlying the hippocampal memory storage. We can explain hippocampal memory formation mechanistically /uniF6DC by activity-dependent changes in synaptic efficacy that lead to altered neural network dynamics (I will elaborate on this idea in chapter 4). We also have a good understanding of the molecular processes underlying synaptic efficacy change. It is now even possible to express synthetic proteins in specific hippocampal neurons and activate them to implant false memories into an animal. As such, of all higher-order brain functions, neural /uniF63A mechanisms of memory are the best understood, largely due to findings from animal studies.

What about animal studies on the hippocampal role in imagination? Is it feasible to study this subject using animals? Definitely. Studies using rats during the last two decades yielded ample evidence that the rodent hippocampus is involved in remembering the past as well as imagining the future. Human and animal studies independently concluded that the hippocampus is involved in imagination as well as memory. More importantly, animal studies have provided significant insights into the neural circuit processes underlying the imagination function of the hippocampus that human studies cannot provide.

WHAT IS A REPLAY?

How did scientists discover the involvement of the rat hippocampus in imagination? By implanting microelectrodes and monitoring hippocampal neuronal activity in real time in freely behaving rats. Neurophysiologists implant microelectrodes in a certain region of the brain, monitor the activity of the neurons there, and then try to understand how that part of the brain processes information by analyzing neuronal activity in association with behavior. Using this approach, scientists found hippocampal 'replays, ' which allowed them to understand the neural circuit processes underlying hippocampal imagination.

A hippocampal replay refers to the reactivation of a past experiencerelated neural activity sequence during an idle state. The sequence of neural activity observed during a rat's active navigation is repeated (or replayed) while the rat is sleeping or resting quietly. We will closely examine the hippocampal replay and how it might be related to the imagination in the rest of the chapter.

PLACE CELL

The most prominent characteristic of hippocampal neurons in freely moving rodents (e.g., rats and mice) is place-specific firing. Hippocampal neurons tend to be selectively active when an animal is within a restricted location of a recording arena. John O'Keefe, a neurophysiologist who reported this finding in rats with Jonathan Dostrovsky in 1971, referred to these neurons as 'place cells. ' With Lynn Nadel in 1978 he also published the influential /uniF63B The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map , which considered the hippocampus the brain structure that represents the layout of the external space. /uniF63C

Later studies have found place cells in the human hippocampus as well. /uniF63D These place cells are thought to be the manifestation of the mental representation of the external space (or cognitive map ). Some neurons in your hippocampus are probably active while you are sitting on a couch in your living room. As you stand up and walk toward the kitchen, different groups of place cells would then be activated in sequence at specific locations along your trajectory to the kitchen. O'Keefe was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2014 for the discovery of place cells that constitute 'a positioning system, an 'inner GPS' in the brain that makes it possible to orient ourselves in space. ' /uniF63E

PARALLEL TETRODE RECORDING

Early studies on place cells focused on how the external spatial layout is represented in the hippocampus. Even though an episodic memory involves a temporal element, only a few researchers attempted to understand how the hippocampus might store a sequence of events. /uniF63F Thus, most early studies focused on hippocampal neural processes for representing static patterns

rather than sequences of events. The discovery of hippocampal replays in the early 2000s changed this research trend dramatically. The team led by Matt Wilson at MIT discovered that sequential firing of hippocampal place cells during active navigation is repeated while rats are sleeping. This discovery set a new trend in research investigating the dynamics of place cells that represent spatial trajectories.

Matt and I worked together for four years in Bruce McNaughton's laboratory as postdocs at the University of Arizona. Matt developed a new recording technique that later enabled the discovery of hippocampal replays and I fortunately witnessed the entire development process as a colleague. Back then, neurophysiologists typically recorded one or at most a few neurons at a time. It was therefore difficult to monitor sequential activity patterns of multiple neurons, which is necessary to study the real-time dynamics of a neural network. Matt developed a new technique, a parallel tetrode recording system, and it allowed simultaneous recordings of up to a hundred hippocampal neurons in freely behaving rats. Rapid progress in research techniques now enables recordings from thousands of neurons simultaneously. In the 1990s, however, a simultaneous recording of up to a hundred neurons was a great leap forward that opened the door for investigating the real-time dynamics of a neural network. Matt continued this line of research and discovered hippocampal replays in the early 2000s.

THETA RHYTHMS, LARGE IRREGULAR ACTIVITY, AND SHARP-WAVE RIPPLES

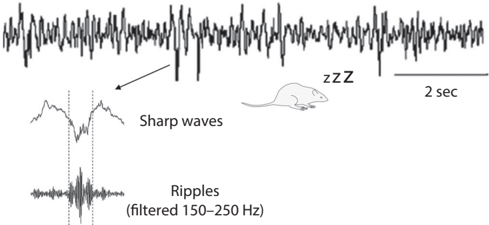

To understand hippocampal replays better, let's first examine two different activity modes of the hippocampus. If you implant a microelectrode and monitor the electrical activity of a rat's hippocampus, you will easily identify two very different activity modes depending on behavioral states. The hippocampus shows strong rhythmic activity at around 6-10 Hz (theta rhythms) when the rat is active. In contrast, when the rat is resting, a slow and irregular rhythmic activity (large irregular activity) is observed along with occasional 'sharp waves' (see fig. 3.1). /uniF640

Sharp waves represent massive synchronous discharges of many hippocampal neurons. Sharp waves occur along with fast oscillations known as 'ripples' (140-200 Hz frequency); thus, they are commonly referred to as sharp-wave ripples . Notably, theta rhythms and sharp-wave ripples are also observed during sleep. Theta sleep in rats is thought to correspond to REM

Running or REM sleep

Quiet rest or deep sleep

FIGURE 3.1. Two activity modes of the hippocampus. Theta rhythms (left) are observed during active movement and REM sleep, while large irregular activity (right) is observed during quiet rest and slow-wave (deep) sleep. Sharp-wave ripples are commonly observed during a period of large irregular activity. Sharp-wave ripples represent massive synchronous discharges of a large number of hippocampal neurons. Panels adapted from (left) Angel Nunez and Washington Buno, 'The Theta Rhythm of the Hippocampus: From Neuronal and Circuit Mechanisms to Behavior,' Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 15 (2021): 649262 (CC BY) and (right) Wiam Ramadan, Oxana Eschenko, and Susan J. Sara, 'Hippocampal Sharp Wave/Ripples During Sleep for Consolidation of Associative Memory,' PLoS One 4, no. 8 (August 2009): e6697 (CC BY).

1 sec

sleep in humans, when most dreams occur, and brain activity is similar to waking levels. Sharp-wave ripples in large irregular activity are observed during slow-wave sleep in rats, which is thought to correspond to deep sleep in humans.

REPLAYS DURING REM SLEEP

Matt first investigated whether the sequential firing of place cells during active navigation is repeated during theta sleep in rats. This was based on the idea that dreams, which occur mostly during REM sleep in humans and, hence, probably during theta sleep in rats, may represent the process of transferring hippocampal memories elsewhere in the brain. As elaborated in chapter 1, the systems-level memory consolidation theory posits that new memory is rapidly stored in the hippocampus and then goes through a consolidation process so that it is eventually stored elsewhere in the brain. /uniF641 Under this theory, it was natural to suspect dreaming as a process of reactivating memories stored in the hippocampus for systems-level consolidation. Indeed, consistent with this hypothesis, Matt and his student, Kenway Louie, found that sequential place-cell firing during active navigation is repeated during theta sleep. This landmark discovery was published in 2001. /uniF6DC/uniF639 The speed of sequential place-cell firing during theta sleep is similar to (in fact, slightly slower than) that during active navigation. This suggests that the progress of events in dreams may be similar to reality.

REPLAYS ASSOCIATED WITH SHARP-WAVE RIPPLES

REM sleep comprises about 25 percent of a night's sleep in humans. In rats, theta sleep represents less than 10 percent of the total sleep period, and the rest is mostly slow-wave sleep during which large irregular activity and sharp-wave ripples are observed. So what happens during slow-wave sleep? If the assumption is that memory consolidation takes place during theta sleep, then does no consolidation take place during slow-wave sleep? Does the brain simply take a rest without processing information? What happens during sharp-wave ripples when a large number of hippocampal neurons are synchronously active?

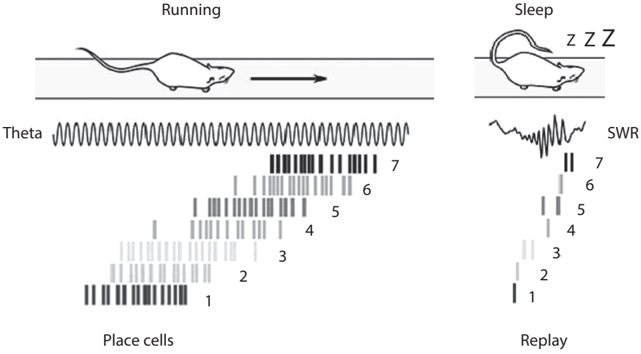

A follow-up study by another of Matt's students, Albert Lee, provided clear answers to these questions. /uniF6DC/uniF6DC A close examination of hippocampal neural activity during sharp-wave ripples revealed that hippocampal neurons fire sequentially on a milliseconds time scale rather than in exact synchrony. More importantly, the sequence of hippocampal neuronal spikes during sharp-wave ripples is not random but is related to sequential firing during active navigation. Place cells tend to fire during sharp-wave ripples in the same sequence that they fired during active navigation before sleep (see fig. 3.2). /uniF6DC/uniF63A The speed of sequential firing is about fifty times faster during sharp-wave ripples than in actual navigation, suggesting that past navigation experiences are replayed in a time-compressed manner during sharp-wave ripples. This monumental discovery paved the way for subsequent research on the hippocampal neural circuit dynamics underlying memory, planning, and imagination. It was followed by a flourish of studies on sharp-wave ripple-associated replays in the rat hippocampus. Now, hippocampal replays generally indicate time-compressed reactivation of sequential hippocampal neuronal discharges that occur together with sharp-wave ripples.

I already mentioned that sharp waves occur during slow-wave sleep as well as during conscious quiet rest (see fig. 3.1). What happens then during sharp-wave ripples in the awake state? Do replays occur during awake sharpwave ripples as well? Later studies demonstrated that hippocampal replays indeed occur in association with sharp-wave ripples during awake quiet rest as well. /uniF6DC/uniF63B Thus, regardless of state (sleep or awake), hippocampal replays appear to occur when sharp-wave ripples are observed.

FIGURE 3.2. Sequential firing of hippocampal place cells during navigation (left) is replayed in a timecompressed manner in association with sharp-wave ripples (SWR) during slow-wave sleep (right). Each tick mark represents a spike. Figure adapted from Celine Drieu and Michael Zugaro, 'Hippocampal Sequences During Exploration: Mechanisms and Functions,' Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 13 (2019): 232 (CC BY).

Note that the hippocampal sharp-wave ripple is common and frequent. It occurs a few times every minute in humans and more frequently in rats during sleep and quiet rest. /uniF6DC/uniF63C In other words, replays of past experiences are likely to be ongoing while we rest or sleep. Considering that neuronal activity often leads to changes in neural network dynamics by inducing long-lasting changes in synaptic efficacy (referred to as activity-dependent synaptic plasticity), it is likely that hippocampal replays occurring during sharp-wave ripples have profound impacts on the representation of recently acquired memories. This suggests that memory consolidation might be ongoing not only during sleep but also during waking periods. That hippocampal replays occur during the awake state also suggests that replays may serve functions other than memory consolidation, such as recalling past navigation trajectories (memory retrieval) and planning future navigation trajectories (planning the future).

REPLAY AND IMAGINATION

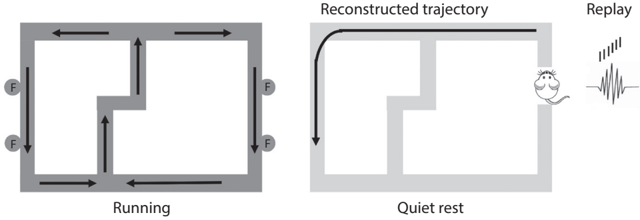

Early studies on hippocampal replays focused on the reactivation of previously experienced place-cell activity sequences. However, a study published in 2010 demonstrated that this is not the whole story. /uniF6DC/uniF63D David Redish and FIGURE 3.3. Replays for unexperienced trajectories. (Left) Arrows indicate the movement directions of a rat. Circles (F) represent food-delivering feeders. (Right) The rat's movement trajectory was reconstructed based on the sequential firing of place cells during a sharp-wave ripple while the rat was sitting quietly on the maze. Note that the rat never traveled along this sample reconstructed trajectory. Figure by author.

colleagues at Minnesota University trained hungry rats on a figure eightshaped maze (see fig. 3.3) to alternatively visit the left and right pathways to obtain food pellets (see the arrows in the figure for the rat's spatial navigation trajectories). They then reconstructed the rat's spatial trajectories according to the sequential discharges of place cells (replays) during sharp-wave ripples. They found that some of the reconstructed trajectories matched those traveled by the rats. Importantly, they also found that some corresponded to trajectories the rats had never experienced before. In other words, hippocampal replays during sharp-wave ripples represent both experienced and unexperienced (but possible) spatial trajectories.

This study was a clear demonstration that hippocampal replays are more than mere reactivations of past experiences. Consider this finding together with what we examined in chapter 1 regarding the role of the hippocampus in imagination. This finding in rats fits well with the finding in humans that the hippocampus plays an important role in imagination. Two independent lines of research using humans and rats arrived at the same conclusion: the hippocampus is involved not only in memory but also in imagination.

REPLAYS IN HUMANS

So far, we have examined replays of sequential place-cell firing found in the rat hippocampus. But are these replays also found in humans? Does the hippocampus support replays of nonspatial sequences as well? Are replays coincident with the activation of the default mode network? Recent studies on humans provide positive answers to these questions.

It is difficult to measure sequential neural activity with the milliseconds time scale (replays) from deep brain regions (the hippocampus and related structures) using a noninvasive technique. Nevertheless, scientists were able to detect neural signatures of replay in the human brain by carefully analyzing brain signals measured by noninvasive techniques. Some commonly used techniques include electroencephalography (an EEG measures weak electrical signals), functional magnetic resonance imaging (an fMRI measures slow changes in blood flow; see chapter 1), and magnetic encephalography (an MEG measures weak magnetic signals from the brain). Each technique has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, MEG is advantageous over EEG for recording neural activity from deep brain structures (such as the medial temporal lobe) and over fMRI for temporal precision.

In recent studies using MEG, human subjects were presented with sequences of visual images. By carefully analyzing weak magnetic signals of the brain during a resting period, scientists were able to reconstruct correct stimulus sequences with a temporal resolution of 50 milliseconds. Notably, these replays were recorded together with the occurrence of sharp-wave ripples in the medial temporal lobe. /uniF6DC/uniF63E These human replays are cortical replays (recorded from the medial temporal cortex) rather than hippocampal replays. Nevertheless, considering that they were coincident with medial temporal lobe sharp-wave ripples and that cortical and hippocampal replays are found together in rats, these findings suggest common neural mechanisms for replay generation in rodents and humans. /uniF6DC/uniF63F

In another study using functional MRI, human subjects were presented with a sequence of images of houses and faces while performing a decisionmaking task. Scientists were able to reconstruct correct sequences on the order of 100 milliseconds based on the hemodynamic signals (changes in blood flow) measured from the hippocampus during conscious rest. /uniF6DC/uniF640 Together, these studies show that replays can be detected in the human brain using noninvasive approaches. Note that these human studies measured replays of nonspatial sequences. Thus, human hippocampal replays are not restricted to the spatial domain.

Notably, in the human subjects, the default mode network is active together with cortical replays and sharp-wave ripples in the medial temporal lobe. /uniF6DC/uniF641 This suggests that two independent findings from animal and human studies, namely hippocampal replay and default mode network activation, may be two sides of a coin. As such, findings from animal and human studies so far fit together nicely, indicating that hippocampal replays are the manifestation of neural processes underlying internal mentation, such as recalling the past and imagining the future, and occur during the activation of the default mode network.

SHARP-WAVE RIPPLE AS A GLOBAL PROCESS

Before wrapping up this chapter, let's examine what happens in the rest of the brain when a hippocampal sharp-wave ripple occurs. To investigate this matter, Nikos Logothetis and colleagues at the Marx-Plank Institute recorded activity of the monkey hippocampus with a microelectrode and monitored the global activity of the brain (regional blood flows) using a noninvasive technique (functional MRI) at the same time. /uniF63A/uniF639 Surprisingly, almost all brain areas showed activity changes synchronized to the occurrence of a hippocampal sharp-wave ripple. Most cerebral cortical areas increased activity, while most subcortical areas decreased activity in association with sharp-wave ripples. For example, the thalamus, a subcortical structure that relays external sensory information to the cerebral cortex, decreases activity with the occurrence of a sharp-wave ripple. Moreover, even though most areas of the cerebral cortex increase activity, the primary visual cortex decreases its activity with a sharp-wave ripple, indicating that the brain disengages from external sensory signal processing at the time of a sharp-wave ripple.

Let's put this together with findings on the default mode network. Sharpwave ripples tend to occur when our default mode network is active, i.e., when we are not paying attention to the external world. At this time, brain areas related to sensory processing (such as the primary visual cortex and thalamus) are silenced, and global information exchanges take place between the hippocampus and the cerebral cortex. Different brain areas appear to do their own jobs when we need to react to the external world, such as when chasing prey. However, when we have the opportunity to relax and can afford not to pay close attention to the outside world, our brains appear to switch off external sensory signal processing and instead allow global information exchange between different brain areas. This occurs when we are engaged in internal mentation, such as remembering the past, imagining the future, making moral decisions, thinking about the thoughts of others, and divergent thinking.

Neuroscience traditionally focused on how the brain processes information when a subject is actively responding to the external world. However, studies on the default mode network and replays suggest that these traditional approaches can tell us only part of the story about the way the brain operates. Recent findings indicate that to understand the principles of brain operation, we need to understand how different parts of the brain synchronize and exchange information during offline states and how these events affect signal processing during subsequent online states. The good news is that studies along this line are actively underway. New findings from these studies may change our traditional conceptual framework for studying the brain.