Chapter Two

FALSE MEMORY

It is now clear that the same brain structure, the hippocampus, is involved in memory as well as imagination. A question then arises as to whether the imagination function of the hippocampus may interfere with its memory function. Wouldn't it be difficult to maintain memory's integrity if it were influenced by imagination? Isn't there a danger of mixing up what we imagined with what we have experienced? In fact, it is well known in psychology that memory is not static but changes over time, and we may even remember events that never happened. The phenomenon of false memory (a recollection that is partially or fully fabricated even though it seems real) raises the possibility that brain regions related to memory and imagination may closely interact with each other. Now, the finding that the hippocampus is involved in both memory and imagination provides a potential account for the neural mechanisms underlying false memory.

WHAT I REMEMBER VERSUS WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED

We do not recollect events exactly as we experienced them. Most often, our recollection of an event differs substantially from the actual event. This is because the way the brain processes and stores information differs from how a computer works. For example, we tend to extract the gist and meaning from our experiences so that what we infer may be mixed up with what we actually experience. If we hear a list of words related to sleep (e.g., bed, rest, awake, etc.), we tend to recollect 'sleep' as being on the list, even though it is not. Also, unlike a computer recovering a file, some memo/uniF6DC ries can interfere with the retrieval of other memories. /uniF63A If a long time has elapsed since experiencing a particular event, and if you have experienced similar events several times since the original experience, chances are you would find it difficult to recollect the original event exactly as it happened; your memory of the original event may get mixed up with memories of related events.

The brain also tends to fill in missing information. Let's pretend you were involved in a traffic accident. You will likely think about the accident from time to time because it is an extraordinary event. During this process, your brain may fill in missing information. For example, even though you initially do not recollect the color of the other driver's clothes because you did not pay attention to it, your brain may fill in this information as you recall the episode afterward. The filled-in information will be strengthened as you repeat this process. As a result, you may vividly recollect that the other driver was wearing a red shirt even though he was in fact wearing an orange shirt. Why red? You may have met many people with red shirts recently. Or you may have watched a movie in which the villain was wearing a red shirt while driving a car. As in this hypothetical example, we tend to fill in missing information with our best guesses based on our expectations and past experiences, which explains why eyewitness testimony can be dangerously unreliable. /uniF63B

THE GEORGE FRANKLIN CASE

Occasionally, we may form a memory of an event that never happened at all. Here, we will examine two suspected cases of such false memory that captured public attention. The first is the case of George Franklin, which originated from a murder in Foster City, California, in 1969. /uniF63C An eight-year-old girl, Susan Nason, was raped and murdered, and the case remained unsolved for years. Twenty years later, Eileen Franklin, a friend of Susan Nason, accused someone of the crime. Surprisingly, the accused was her father, George Franklin. Eileen testified in court that she witnessed George crushing Susan's skull with a heavy rock. She said that a vivid memory of the horrible scene,

which had been forgotten for twenty years, suddenly flashed into her mind as she was playing with her young daughter, Jessica.

Eileen Franklin's testimony initiated a controversy between repressed memory and false memory. Repressed memory is a concept originally postulated by Sigmund Freud as a defense mechanism against traumatic events. The mind may unconsciously block access to horrific memories, which may be recovered years later. This idea was widespread among clinical psychologists and ordinary people at the time of George Franklin's trial. With no physical evidence other than his daughter's testimony, the jury found him guilty of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Contrary to the jury's verdict, the following discussion argues for false memory rather than repressed memory. First, the postulated repressed memory has not been proven scientifically. Second, memories change over time. It is therefore questionable whether Eileen could recollect details of an event exactly as it happened twenty years earlier. Third, all the details she provided about the murder could be found in newspaper articles. Furthermore, some details were incorrect in both the newspaper articles and Eileen's statement. For example, one article mistakenly stated that the ring Susan was wearing on her right hand contained a stone (the ring with a topaz stone was in fact on her left hand), and Eileen made the same error. Fourth, it was revealed later that Eileen recalled the memory through hypnosis. Hypnotically refreshed testimony is not allowed in court because the witness's memory can be contaminated with misinformation. Correct and incorrect information may get mixed into a coherent narrative during hypnosis, which increases the confidence of the witness about the refreshed memory. Fifth, Eileen later accused her father of two additional cases of rape and murder (Veronica Cascio and Paula Baxter), but DNA tests cleared him of the charges. This called into question the credibility of Eileen's testimony. In 1996, he was released from prison. In 2018, another man, Rodney Lynn Halbower, received life sentences for those two murders. /uniF63D

THE PAUL INGRAM CASE

In 1988, Paul Ingram, who was then the chief civil deputy of the Thurston County Sheriff's Office in Olympia, Washington, was accused by his two daughters, twenty-two-year-old Ericka and eighteen-year-old Julie, of sexually abusing them for years when they were children. He initially denied the charges but eventually admitted that he sexually abused his daughters during satanic rituals. Since he pleaded guilty, it seemed that the case was resolved with no controversy.

This seemingly simple case unfolded into a complicated tale, however. Ericka's accusations were gradually amplified to grandiose stories of ritual abuse that included baby sacrifices, for which the police failed to find physical evidence. For example, she insisted that she watched twenty-five babies being sacrificed during the rituals and that they were buried in the family's backyard. However, no human bones (only a fragment of an elk bone) were found on the property. In fact, months of police investigation, the most extensive in the county's history, yielded no physical evidence whatsoever for the claimed rituals or homicides. /uniF63E

What about Paul's recollection of satanic rituals? A 'little experiment' performed by Richard Ofshe, a social psychologist from the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that his confessions may be 'coercedinternalized false confessions. ' Ofshe joined the investigation as an expert /uniF63F in cults and mind control, but he was also interested in coercive police interrogations. He introduced a false allegation that Paul forced his son and daughter to commit incest with each other. Paul initially denied this accusation but eventually wrote a detailed confession on it. He even refused to believe that the incident was false when Ofshe revealed that he had made it up. /uniF640 It is still unclear whether Paul's confessions reflect what happened, false memories, or a mixture of both. Nevertheless, together with the George /uniF641 Franklin case, Paul Ingram's case contributed to the public awareness that misinformation and suggestions by authoritative figures, such as trusted psychologists or police officers, may implant false memories in the psyche of susceptible people.

LOST IN A SHOPPING MALL

The two preceding cases suggest that we may fabricate memories of events that never actually happened. Elizabeth Loftus, a psychology professor at the University of Washington, provided expert testimony on this possibility in the George Franklin trial. Despite her testimony, he was convicted in 1990. Her studies until then proved that memories could be altered by information received after an event (known as the misinformation effect ) but did not prove that memories could be wholly invented. /uniF6DC/uniF639

To prove the possibility of totally fabricated event memories, Loftus, with her student Jacqueline Pickrell, ran an experiment-the 'lost in a shopping

mall' study-and published the results in 1995. /uniF6DC/uniF6DC Twenty-four subjects were given four short stories about events from their childhood and instructed to record details of their memories of them. They were then interviewed twice, with each interview conducted over a span of one to two weeks. Three of the four stories were true, but one was a false event about getting lost. For example, the following summary was given to a twenty-year-old Vietnamese American woman: 'You, your mom, Tien, and Tuan all went to the Bremerton K-Mart. You must have been 5 years old at the time. Your mom gave each of you some money to get a blueberry Icee. You ran ahead to get into the line first and somehow lost your way in the store. Tien found you crying to an elderly Chinese woman. You three then went together to get an Icee. '

On the one hand, most people (18 of 24 or 75 percent) denied having the memory of getting lost and successfully remembered 49 of the 72 true events (a 68 percent success rate). The amount of details, clarity rating, and confidence rating were also much greater for the memories of the true events, indicating that our event memories are reasonably reliable.

On the other hand, six subjects (25 percent) said they remembered, fully or partially, the event of getting lost in their childhood, showing that it is possible to implant, by misinformation and suggestions, false memories of events. The following is an example from one subject, who falsely believed that she had truly been lost during the second interview: 'I vaguely, vague, I mean this is very vague, remember the lady helping me and Tim and my mom doing something else, but I don't remember crying. I mean I can remember a hundred times crying. . . . I just remember bits and pieces of it. I remember being with the lady. I remember going shopping. I don't think I, I don't remember the sunglass part. '

A PICTURE IS WORTH A THOUSAND LIES

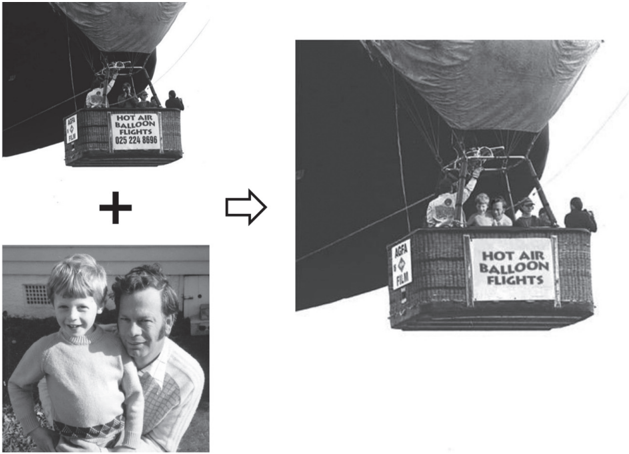

The result of the 'lost in a shopping mall' study has been replicated in subsequent studies. Let's examine one that employed a fake visual image. /uniF6DC/uniF63A Twenty subjects who had never taken a hot-air balloon ride before were presented with a doctored photograph showing them riding in a hot-air balloon (see fig. 2.1). They were then interviewed three times over the next seven to sixteen days. By the third interview, ten subjects (50 percent) claimed that they remembered at least some details of the balloon ride (consistent elaboration of information not shown in the fake photo was required to be qualified as a false memory). The following is from the third interview with a subject who was rated to have developed a partial false memory:

FIGURE 2.1. Photoshopped images generated for use in a false memory study (courtesy of Kimberly Wade).

Interviewer: Same again, tell me everything you can recall about Event 3 without leaving anything out.

Subject: Um, just trying to work out how old my sister was; trying to get the exact . . . when it happened. But I'm still pretty certain it occurred when I was in form one (6th grade) at um the local school there. . . . Um basically for $10 or something you could go up in a hot air balloon and go up about 20 odd meters . . . it would have been a Saturday and I think we went with, yeah, parents and, no it wasn't, not my grandmother . . . not certain who any of the other people are there. Um, and I'm pretty certain that mum is down on the ground taking a photo.

This study corroborates the conclusion that we may form false memories of events. More subjects developed a false memory in the hot-air balloon study than in the lost-in-the-mall study. This is perhaps because the subjects saw a clear, albeit fake, visual image (see fig. 2.1). After all, isn't a picture worth a thousand words? The authors metaphorically titled this study ' A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Lies. '

CONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY

We started this chapter with the issue of potential interactions between memory and imagination. Given that the hippocampus is involved in both memory and imagination, isn't it possible to mix up what we imagined with what we have actually experienced? The answer is clear. Imagination does influence memory, so it is even possible to implant fabricated memories under certain circumstances. Pretend you are one of the study's participants: It seems to be true that you once got lost in a shopping mall during the childhood because your mom and brother said so. You don't have a clear memory of that event, but you were asked to recall and write down episodic details of it. Here, imagination may slip into the recalling process, gradually filling in episodic details of a false memory.

Contrary to common sense, memory and imagination may not be two independent processes; our memory clearly relies on constructive processes that are sometimes prone to error and distortion. Daniel Schacter, a psychologist at Harvard University, named this aspect of memory constructive memory : 'When we remember, we piece together fragments of stored information under the influence of our current knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. ' /uniF6DC/uniF63B Imagination is also a process of piecing together fragments of stored information. If so, it would be more efficient for the brain to share a common constructive process for memory and imagination rather than maintaining two independent processes. From this perspective, it would not be surprising to learn that the hippocampus is involved in both memory and imagination. Although it is not favorable for remembering an event precisely as it happened, it is adaptive in that it 'enables past information to be used flexibly in simulating alternative future scenarios without engaging in actual behaviors. ' /uniF6DC /uniF63C

We do not yet clearly understand the exact neural processes underlying the constructive aspect of memory. However, from the standpoint of the hippocampus, both memory and imagination may be manifestations of the same underlying neural processes. In the following chapters, we will explore the hippocampal neural processes underlying memory and imagination.