Chapter Fourteen

THE FUTURE OF INNOVATION

Is human capability for innovation a blessing? In terms of competing with other species, it definitely is. Humans' ability to innovate has allowed them to dominate other large animals. Figure 14.1 shows the weight distribution of vertebrate land animals. Ten thousand years ago, the total weight of humans comprised only 1 percent and the rest was contributed by wild animals. Now, the corresponding numbers are 32 percent and 1 percent, respectively, and the total weight of livestock (cows, sheep, horses, chickens, etc.) exceeds the combined weight of all humans and wild animals. This illustrates how dominant humans are over other large animals.

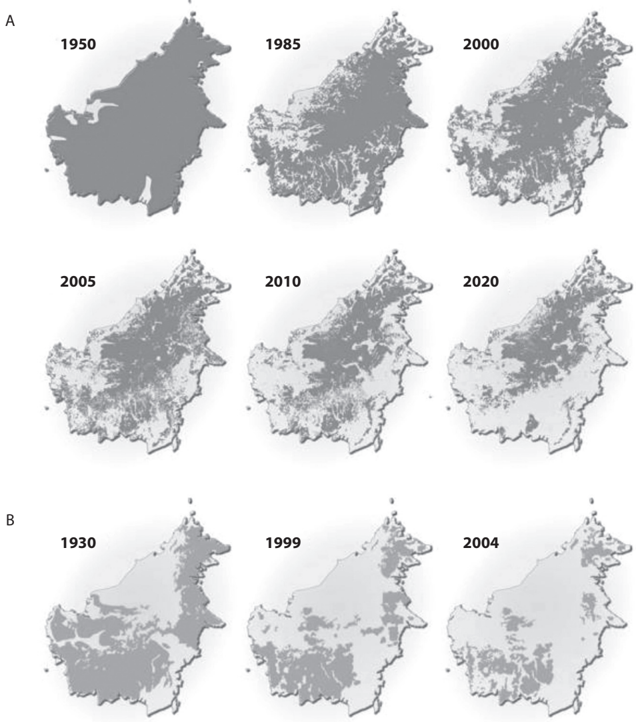

Unfortunately, the human capacity for innovation may turn out to be a curse rather than a blessing in the long run if not properly controlled. The ecosystem is being destroyed on a global scale because of human activities such as overexploitation of natural resources (see fig. 14.2), habitat destruction (see fig. 14.3), and climate change due to the overuse of fossil fuels. We may have to worry about our own extinction soon if the current trend continues.

What awaits us if we continue on our current path of innovation? Will it be a utopia or a dystopia? Predicting the future is far more difficult than looking back in time. Nonetheless, we can try to predict what will happen next based on what has happened in the past. Let's look at two opposing points of view, one pessimistic and one optimistic.

PESSIMISTIC PERSPECTIVE

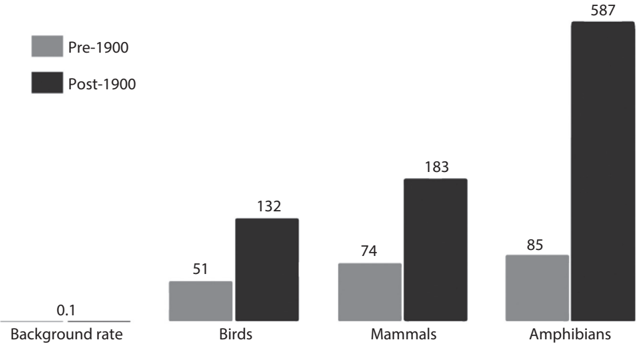

There have been five mass extinctions in the history of the earth. The most recent one took place sixty-five million years ago. Many animals, including all non-avian dinosaurs, went extinct. Luckily for us, mammals took this opportunity to thrive, eventually leading to the evolution of primates including humans. Now, the sixth mass extinction may be underway because of human activities. According to a study on vertebrates, the extinction rate during the past five hundred years is hundreds to thousands of times faster than an ordinary one, which is 0.1 extinction per million species per year (0.1 E/MSY), and the rate has been accelerating since 1900 (see fig. 14.4). According to World Wildlife Fund's Living Planet Report 2022, the relative abundance of monitored wildlife populations decreased by 69 percent around the world between 1970 and 2018. The decline is especially steep in freshwater species populations (80 percent) and, regionally, in Latin America (94 percent). The current trend of extinction, if continues, may eventually include Homo sapiens as a victim.

The ongoing climate change is particularly concerning. All life species face the challenge of adapting to their ever-changing environment. Environmental changes may contribute to ecological diversity by forcing existing species to evolve into new species. However, if the changes are too abrupt or drastic for most living species to adapt to, they may face mass extinction.

Historically, cataclysmic events such as large-scale volcanic eruptions and asteroids induced drastic changes in the environment, killing a large portion of existing species. The most severe mass extinction, known as the great dying, took place 251.9 million years ago. Up to 96 percent of all marine species and around 70 percent of all land species died out. Scientists believe that massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia released immense amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere over a short period. This caused abrupt global warming and a cascade of other deleterious environmental effects such as weathering (dissolving of rocks and minerals on the earth's surface), which reduced the oxygen level in the ocean. These environmental changes were too drastic for most species to adapt.

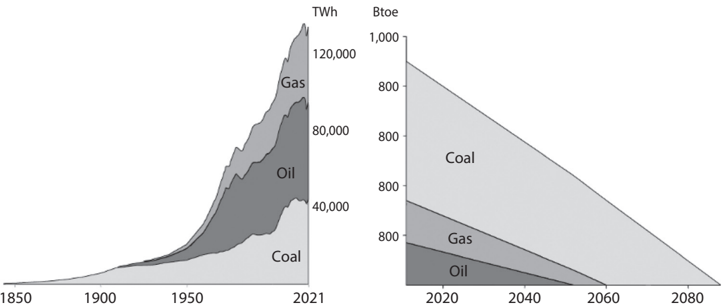

The bad news is that human activities, especially the massive use of fossil fuel, appear to be inducing abrupt and drastic environmental changes that are as severe as those during past episodes of mass extinction. The fossil fuel we currently use is the outcome of a long-term carbon-trapping process. Dead plants were converted into peat instead of being degraded during the Carboniferous period (about 360 to 300 million years ago) and eventually turned into coal, oil, and gas. However, we are now reversing that process in only a few hundred years (see fig. 14.5)! It is not so surprising then that fossil fuel overuse induces climate change too quickly and drastically for many life species to catch up.

Why were dead plants not degraded during the Carboniferous period? According to the most popular theory, there was a sixty-million-year gap between the appearance of the first forests and wood-digesting organisms (the evolutionary lag hypothesis). In other words, there were no organisms that could break down wood during that period. A significant event in the history of plant evolution is the appearance of lignin, which is a class of complex organic polymers. Together with cellulose, lignin provides rigidity to land plants, allowing them to grow tall, which is advantageous for effectively harnessing the primary source of energy-sunlight. Ancient microorganisms could not break down lignin and so dead plants piled up and didn't disintegrate. In a sense, lignin was like present-day plastic. It took sixty million years for lignin-digesting bacteria and fungi to evolve. Perhaps new organisms that can break down plastic will eventually evolve so that the current plastic crisis will be resolved. It just may take an extremely long time-and another sixty million years is two hundred times the entire span of existence of Homo sapiens.

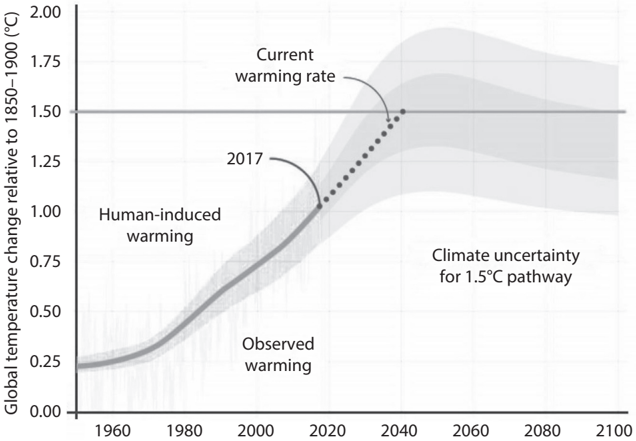

Currently, the most significant consequence of fossil fuel overuse is global warming. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report, the global temperature rose approximately 1°C above pre-industrial (between 1850 and 1900) levels by 2017 (see fig. 14.6). That increase in less than one hundred years is an extremely rapid change on a geological time scale; it rivals the rate of global warming during the great dying. Many organisms are dying out because they cannot keep up with such rapid environmental changes. Evolution is a slow process for most species, so if this trend of global warming continues, the rate of extinction will likely accelerate.

To strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, 195 nations adopted the Paris Agreement in December 2015 to limit the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. If the participating nations faithfully abide by the agreements, i.e., reduce emissions immediately, and have CO₂ emissions reach zero by 2055, the global temperature is predicted to reach 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels around 2040 and then either reach a plateau or slightly overshoot the target.

Why 1.5°C? This is because the chance of crossing a 'tipping point' is greatly increased with global warming above that level. Irreversible changes may occur and global warming may accelerate greatly once we cross that tipping point. For example, global warming decreases glacier mass, which in turn decreases glaciers' reflection of the sun's rays, resulting in further global warming. Another example is the thawing wetlands in Siberia's permafrost that release methane gas and exacerbate global warming. Above the tipping point, global warming may interact synergistically with its consequences, such as glaciers melting (see fig. 14.7), thawing of arctic wetlands, forest destruction due to droughts and fire, and slowing of ocean circulation. Once some of these events get started, it may not be possible to reverse what human activity began.

Unfortunately, there are concerns that the actions to fulfill the pledges under the Paris Agreement are insufficient. For example, wealthy countries have not kept their pledge to provide poorer countries with one hundred billion dollars per year in climate finance. Worse, the United States, a major emitter of greenhouse gases, withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2020 under the Trump administration. The current climate change dilemma could be a classic example of the 'tragedy of the commons,' which refers to a situation in which self-interested people (or organizations) with access to a common resource eventually exhaust that resource. It is a relief that the United States rejoined the Paris Agreement in 2021 under the Biden administration. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility of crossing a tipping point even if we faithfully abide by the pledges under the Paris Agreement. If we fail to do so, the chance for crossing a tipping point will increase greatly.

Global temperature changes of a few degrees may not be a big deal in the geologic time scale. The global atmospheric temperature has fluctuated substantially since the birth of life on earth. It was warmer than the present day by 5 to 10°C during the Jurassic Period (approximately 150-200 million years ago) when dinosaurs flourished, and cooler than the present day by about 6°C in the last ice age (approximately twenty thousand years ago). Therefore, a change of one or two degrees in global atmospheric temperature isn't a significant event from the earth's standpoint. However, it would be a big concern for some of the planet's currently flourishing species, such as Homo sapiens. More than 99 percent of all species that have ever lived are now gone. The global atmospheric temperature has been stable for the last ten thousand years, during which mankind has achieved stunning success in increasing its number, expanding its territory, and building civilizations. However, if the current trend of global warming continues and crosses a tipping point, mankind may soon have to face an extremely harsh future.

OPTIMISTIC PERSPECTIVE

So far we have taken a gloomy look at the current trend of global warming. Now let's look on the bright side. First, we are aware of the potentially catastrophic consequences of global warming. Second, we have a decent scientific understanding of the human factors causing global warming. Third, we are taking actions to mitigate it. It is, of course, difficult to predict and control climate dynamics because of its immense complexity. Nevertheless, it is encouraging that people are making an effort to understand global events and mitigate their adverse consequences.

Recognizing that certain substances, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were widely used as refrigerants, can damage the stratospheric ozone layer, an international treaty, the Montreal Protocol, was adopted in 1987 to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of ozone-depleting substances. How effective was this treaty? The estimated effect of the Montreal Protocol since 1987 amounts to the reduction of the global atmospheric temperature by 0.5-1°C by 2100. This is an enormous success. The case of the Montreal Protocol delivers a powerful and encouraging message that we can stop further climate change.

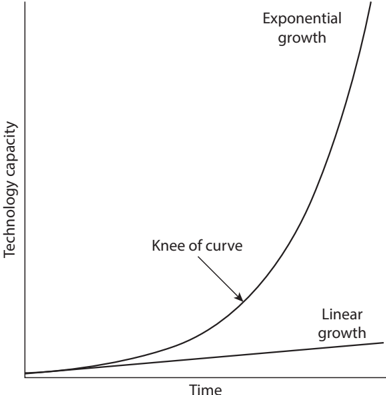

Another source of optimism is the rapid pace of scientific and technical advancements. Technology grows exponentially rather than linearly. Such rapid technological advancements may provide us with the means to combat our current environmental issues. We may soon be able to develop technologies that are immensely more powerful than those now in use. We may be able to address current and future environmental challenges with the help of these technologies.

Consider how artificial intelligence is evolving. Given the current rate of scientific progress, we may soon be able to understand the key neural principles underlying human intelligence and then use this knowledge to develop artificial intelligence that outperforms human intelligence. This is already happening in some ways. For instance, we discussed how the depth of a neural network may be critical in determining the degree of abstraction it can achieve (see chapter 11). Deep learning now employs neural networks with well over a hundred layers, far exceeding the depth of the network found in the human brain.

Artificial intelligence already outperforms humans in many domains. The critical next stage is the development of a general-purpose artificial intelligence. In this regard, David Silver and colleagues at DeepMind, in their paper titled 'Reward Is Enough,' proposed that reward is sufficient to develop a general-purpose artificial intelligence. According to their hypothesis, most, if not all, forms of intelligence, including perception, memory, planning, motor control, language, and social intelligence, emerge as a result of the overarching objective of maximizing reward. This is because maximizing reward in a complex environment requires a diverse array of abilities. Given that reinforcement learning formalizes the problem of goal-seeking intelligence, a sufficiently powerful reinforcement learning agent interacting with complex environments would develop various forms of intelligence necessary to maximize reward across multiple environments.

AlphaGo shocked the world by defeating Lee Sedol, a human Go master, in 2016. DeepMind created additional programs, such as AlphaZero and MuZero, over the ensuing years. MuZero, a powerful reinforcement learning agent, was able to master numerous board games (Go, Chess, and Shogi) as well as a number of Atari games with no prior knowledge of them. MuZero could learn to master all of these games with the single objective of maximizing reward (e.g., winning a game), despite the fact that different types of knowledge are required for different games. We may soon see the emergence of artificial general intelligence if this line of research continues.

The inventor and futurist Ray Kurzweil, highlighting the exponential nature of technological growth (the 'law of accelerating returns'), predicted that 'the technological singularity' (the point at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible) would occur in 2045. Once we reach the singularity, artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence and continue to improve at an ever-accelerating rate without human intervention, triggering a self-improvement runaway reaction. In 1966, the mathematician Irving Good predicted an 'intelligence explosion' and the emergence of artificial superintelligence as follows: 'Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an 'intelligence explosion,' and the intelligence of man would be far left behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.'

One hopeful outcome of this intelligence explosion is the development of new and powerful technologies capable of halting or even reversing current environmental problems. This may not appear plausible from the standpoint of contemporary technology. However, once technological advances reach a tipping point, progress may far outpace what we can currently imagine.

Can the pace of technological progress continue to speed up indefinitely? Isn't there a point at which humans are unable to think fast enough to keep up?

For unenhanced humans, clearly so. But what would 1,000 scientists, each 1,000 times more intelligent than human scientists today, and each operating 1,000 times faster than contemporary humans (because the information processing in their primarily nonbiological brains is faster) accomplish?... When scientists become a million times more intelligent and operate a million times faster, an hour would result in a century of progress (in today's terms).

Kurzweil predicted a number of events that would occur following the singularity, including the ability of nanobots to reverse the pollution caused by earlier industrialization. I hope anticipating technology that can stop current global warming is not naive optimism. Exponential knowledge growth, which includes advances not only in science and technology, but also in our understanding of human nature and society, as well as optimizing strategies for organizing and mobilizing social resources, may provide us with effective tools to address the current environmental challenges.

Linear and exponential growth appear comparable in the early stages. Their differences become apparent only when the growth reaches a certain threshold (the knee of the exponential curve; see fig. 14.8). From this perspective, it appears that we are currently living in an era in which the exponential growth of technology is beginning to accelerate past a critical point.

Let me illustrate this idea with a few examples derived from my personal experiences. In 1981, as a biology student, I took a molecular genetics course. I recall the awe I felt when I first learned about the molecular processes underlying the central dogma (the transfer of information from DNA to messenger RNA to protein), which is a fundamental principle underlying all life forms on earth. The potential of gene cloning (or recombinant DNA) technology was mentioned only briefly in the textbook's last chapter. Gene cloning is the process of making multiple copies of a gene. Using restriction enzymes (enzymes that cut DNA at certain nucleotide sequences), a specific DNA sequence is cut, inserted into a vector (a small piece of DNA that can replicate independently of the host genome), and then introduced into a host cell. This marked the beginning of genetic engineering. Since then, genetic engineering technologies have advanced rapidly. CRISPR-CAS, a relatively new technology, in particular, enables precise editing of DNA sequences in living organisms. These genetic engineering technologies are now being used in conjunction with other technologies, such as big data science and artificial intelligence, to design and build new biological parts, devices, and systems that do not exist in nature. One could, for example, try to design and create new microorganisms that degrade plastic. This is an emerging field known as synthetic biology. Scientists confirmed that DNA is the genetic substance in 1944. Less than a hundred years later, scientists have identified the genetic code (a triplet of nucleotides specifying one amino acid), molecular processes underlying the central dogma, and the entire human genome sequence, and they can now design and manufacture new life forms.

Rapid advances in computer technology are another example. Another course I took in 1981 was computer programming. Back then, we had to write codes on squared paper and submit them to a punch-card operator. After a few days, we would receive a thick bundle of punch cards, which we then brought to a computer center for the main computer to read and generate the output. The main computer read the data from the punch cards (based on the absence or presence of a hole at a specific location) and generated the final output. Even a very short program required a thick stack of punch cards.

I first encountered a personal computer when I went to the United States for graduate school in 1986. It was a whole new experience for me—my inputs immediately produced results on the computer screen. I could even write and run a program without using punch cards! The hard disk of the computer I was using at the time—I think it was an IBM XT—had to be backed up one day because it was almost full. The total disk space of the computer was 10 MB. I used about twenty or so floppy disks (525 KB each) to back up the disk. Now, about thirty-five years later, my smartphone has 256 GB of disk space, which is 25,600 times more than that computer from the 1980s. The speed and capacity of computers have been doubling approximately every two years for the past few decades, according to Moore's law. This means that today's computers are about 100 times more powerful than those 14 years ago, 10,000 times more powerful than those 27 years ago, and 1 million times more powerful than those 40 years ago. As such, the advancement of computer technology has been visibly exponential for the past few decades.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is another field that is rapidly progressing. Since the deep learning revolution, many powerful AI programs have emerged that far outperform humans in various domains. Even in fields such as art, music, and literature, which were once thought to require special human abilities, powerful AI programs are now available. They can create music, drawings, videos, or even poems and novels. The following is a poem chatGPT wrote after I requested it to 'write a poem on human creativity.'

Creativity flows like a river wild, A force that cannot be tamed or reconciled. It bursts forth from the depths of the mind, A spark that sets the imagination aligned.

It dances in the brushstrokes of a painter, It sings in the notes of a composer's gainer. It shapes the words of a poet's pen, And the designs of an engineer's den.

It builds the bridges that span the divide, And the skyscrapers that reach for the sky. It brings to life stories that touch the soul, And the inventions that make us whole.

Human creativity is a wonder to behold, A reflection of the world, both young and old. It is the light that guides us through the dark, A reminder of the beauty in our hearts.

ChatGPT wrote this poem in a matter of seconds. It'll probably take me a month or more to write a poem as good as this one.

If powerful AI technologies continue to advance exponentially and are combined with technological breakthroughs in other areas, they may become effective in combating the environmental issues we are currently facing. DeepMind was able to save 40 percent of total cooling costs by applying AI technologies to the control of Google data centers. This is a significant improvement given that Google data centers were already managed in a highly sophisticated manner prior to the application of DeepMind's AI. This example shows how AI can be used to improve energy efficiency and minimize emissions.

CROSSROADS

We might be approaching a crossroads where, on the one hand, technological advancements begin to take off and, on the other hand, excessive exploitation of natural resources threatens the continued existence of our own species. The COVID-19 pandemic might be evidence of both of these trends. The pandemic is the result of the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is believed to have originated in bats before spreading to humans. As people continue to invade wildlife habitats, the risk of zoonotic disease (animal-borne infectious disease for humans) will inevitably increase. There is always the possibility of a new zoonotic disease, such as COVID-19, that is both highly infectious and fatal. However, advances in science and technology have provided us with the means to deal with COVID-19. Some countries were able to keep their case numbers and fatalities relatively low by implementing early lockdown procedures, widespread testing, contact tracing, isolation, and effective communications with citizens. Various technologies, such as disease diagnosis, the internet, and smartphones, played roles in this process. More significantly, we were able to develop effective vaccines in less than a year after the COVID-19 outbreak, which is unprecedented in human history. This was made possible by the vast corpus of technological and scientific advancements humanity has amassed over centuries in a range of disciplines, including biology, chemistry, and engineering.

The genus Homo is estimated to have appeared approximately three million years ago. Many Homo species have since gone extinct and currently only one, Homo sapiens, is alive. Neanderthals and Denisovans existed for about two to three hundred thousand years and Homo erectus for about two million years. And Homo sapiens? Approximately three hundred thousand years so far. How much longer can we survive? We cannot anticipate a bright future if the current trend of global environmental changes continues. We cannot exclude the possibility that Homo sapiens—and by extension, the entire genus Homo—will go extinct in the not-too-distant future. Alternatively, the rapid advances in science and technology may offer us effective ways to battle the consequences of global environmental changes.

Can humans use their capability for innovation to overcome the crisis of global environmental change and sustain civilizations? Or will they run out of time in dealing with the impending environmental disaster? Our journey may lead us where scientific and technological advancements enable humans to overcome current and future challenges and transcend biological constraints (utopia). On the contrary, our path may lead to the bleak consequences of a new mass extinction; we may end up facing extremely harsh conditions, including food scarcity, that will demolish the infrastructure of the civilizations humanity has built throughout history (dystopia). The remainder of the twenty-first century may prove crucial for humanity's future.