Chapter Twelve

SHARING IDEAS AND KNOWLEDGE THROUGH LANGUAGE

'If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.' This famous quote in a letter from Isaac Newton to another eminent and rival scientist, Robert Hooke, is frequently used to symbolize how scientific progress is made. Discoveries, inventions, and innovations rarely occur in a vacuum. We rely on the knowledge gained by our predecessors to make intellectual progress.

Galileo Galilei, who died in the year Newton was born (1642), was one giant whose shoulders Newton stood on. Galileo laid down the foundation for understanding the motion of an object, including the formulation of the concept of inertia (an object remains in the same state of motion unless an external force is applied), which greatly influenced Newton. Johannes Kepler was another giant for Newton. Kepler, using the astronomical data Tycho Brahe collected over decades, discovered laws of planetary motion. Building on Kepler's work, Newton developed general laws of motion that can explain all motion, be it the orbit of the Earth around the Sun or an apple falling from a tree. Before Newton was born, Galileo and Kepler were able to see further than their contemporaries because they stood on the shoulders of Nicolaus Copernicus, who developed a heliocentric (Sun-centered) model of the solar system.

We have, thus far, considered neural mechanisms behind an individual's thought processes enabling innovation, focusing on imagination and abstraction. But we have not paid much attention to another critical faculty of the human mind for innovation, namely the capacity to share ideas and knowledge. For the advancement of science and technology, such as those shown in fig. 0.1, social communication involving high-level abstract concepts is essential. It is difficult to imagine a human civilization as complex and advanced as today's without language. In this respect, acquiring linguistic capacity represents an important step in human evolution, as described by Mark Pagel: 'Possessing language, humans have had a high-fidelity code for transmitting detailed information down the generations. The information behind these was historically coded in verbal instructions, and with the advent of writing it could be stored and become increasingly complex. Possessing language, then, is behind humans' ability to produce sophisticated cultural adaptations that have accumulated one on top of the other throughout our history as a species.'

In this chapter, we will explore language, a unique form of human communication, which elevated mankind's collective creativity to a new dimension. We will examine a few selected topics of language, including its neural basis, its relationship with abstract thinking, and its origin.

UNIVERSALITY OF LANGUAGE

Language is a system by which sounds, symbols, and gestures are used according to grammatical rules for communication. No mute tribe has ever been discovered, indicating that language is universal in all human societies. Although there are many different languages (more than seven thousand languages and dialectics throughout the world), all languages are used in similar ways—to elaborate personal experiences, to convey subtle emotions, to solicit information (ask questions), and to make up stories (sometimes for deception), along with many other facets of human communication. The process of language acquisition is also similar across all cultures. Moreover, there is a critical period during which children learn to use a language effortlessly without any formal training if they are exposed to a normal linguistic environment. Pagel further explains, 'All human languages rely on combining sounds or 'phones' to make words, many of those sounds are common across languages, different languages seem to structure the world semantically in similar ways, all human languages recognize the past, present and future and all human languages structure words into sentences. All humans are also capable of learning and speaking each other's languages.' The universality of language suggests that the human brain has evolved special language-processing systems.

THE UNIQUENESS OF HUMAN LANGUAGE

Language is often placed at the top of the list for the criteria that separate humans from other animals. Although other animals besides humans communicate with each other, it is doubtful that animal communication can be considered language. The following commonly mentioned features of human language are either absent or substantially limited in the other animals' communications:

Discreteness: Human language consists of a set of discrete units. The smallest unit of speech is a phoneme (or a word sound). Forty-four discrete phonemes in English distinguish one word from another. For example, the words cat and can share the first two phonemes, and c a, but differ by the last one. At another level, individual words are combined to construct phrases and sentences. There are sentences made up of five or six words, but there are no sentences made up of five and a half words. Cat and can are distinctly different words, and there is no meaning in-between them.

Grammar: Rules govern the underlying structure of a language. Linguistic units are combined according to these rules to express meanings.

Productivity: There is no upper bound to the length of a sentence one can construct with words. Humans have the ability to produce an infinite number of expressions by combining a limited set of linguistic units.

Displacement: Humans can talk about things that are not immediately present (e.g., past and future events) or that do not even exist (e.g., imaginary creatures on Mars).

We combine discrete units of language (e.g., words) according to grammatical rules to generate indefinite utterances (e.g., sentences) that include things that do not even exist. Many animal species are capable of sophisticated communication that shows some of the features of human language. For example, the waggle dance of a honeybee describes the location and richness of a food source, and prairie dog alarm calls vary according to predator type and individual predator characteristics including color and shape. However, no animal communication system displays all the features of human language. Human language is a complex, flexible, and powerful system of communication. The creative use of words according to rules can generate unlimited expressions. No other animal communication comes close to human language.

CAN ANIMALS BE TAUGHT HUMAN LANGUAGE?

Animals' natural communication falls short of human language, but is it possible to teach animals to use language? The question is whether other animals can be trained to combine symbols in original ways according to some grammatical system to express new things. There have been numerous attempts to teach animals (such as chimpanzees and dolphins) human language, and the results are controversial. Let's examine the case of Koko (July 4, 1971-June 19, 2018), a female western lowland gorilla that learned and lived in a language environment (sign language and spoken English) from the age of one. It has been claimed that Koko was able to combine vocabularies in 'creative and original sign utterances.'

Koko has generated numerous novel signs without instruction, modulated standard signs in ASL (American Sign Language) to convey grammatical and semantic changes, used signs simultaneously, created compound names (some of which may be intentional metaphors), engaged in self-directed and noninstrumental signing, and has used language to refer to things removed in time and space, to deceive, insult, argue, threaten, and express her feelings, thoughts, and desires. These findings... support the conclusion that language acquisition and use by gorillas develops in a manner similar to that of human children.

The following is a conversation in sign language between the trainer, Francine Patterson (denoted as 'F'), and Koko (denoted as 'K') about Koko's favorite kitten, All Ball, who died in a car accident a few months earlier:

- F: How did you feel when you lost Ball?

- K: WANT.

- F: How did you feel when you lost him?

- K: OPEN TROUBLE VISIT SORRY.

- F: When he died, remember when Ball died, how did you feel?

- K: RED RED RED BAD SORRY KOKO-LOVE GOOD.

This was interpreted as Koko's expression of sad feelings about the death of All Ball. However, skeptical scientists suspect whether Koko, and other language-taught animals as well, were truly able to combine symbols in creative ways. We cannot exclude the possibility that these animals learned to act in certain ways under certain circumstances (simple stimulus-response associations) to get a reward without understanding the meaning behind their actions. For example, they may have learned to make certain actions in response to the trainer's subtle unconsciousness cues. This is commonly called the 'Clever Hans effect':

In the first decade of the 20th century, a horse named Hans drew worldwide attention in Berlin as the first and most famous 'speaking' and thinking animal. ... Hans performed arithmetic operations precisely, tapping numbers with his hoof, and answered questions in the same way, using an alphabet with letters replaced by numbers (A = 1, B = 2, C = 3...) on a blackboard in front of his eyes. Thus Hans combined letters to words, words to sentences, and sentences to thoughts and ideas. ... Professor Oscar Pfungst ... found that the horse was unable to answer any question if the questioning person did not know the answer. ... Furthermore, the horse was unable to answer any question when a screen was placed such that it could not see the face of his examiner. ... It turned out that the horse was an excellent and intelligent observer who could read the almost microscopic signals in the face of his master, thus indicating that it had tapped or was about to tap the correct number or letter and would receive a reward. In the absence of such a signal, he was unable to perform. Indeed, Pfungst himself found that he was unable to control these clues as the horse continued to answer correctly when his face was visible to it.

Another concern is that Koko's signs had to be interpreted by the trainer. 'Conversations with gorillas resemble those with young children and in many cases need interpretation based on context and past use of the signs in question. Alternative interpretations of gorilla utterances are often possible.' A sequence of hand signs that were interpreted as 'you key there me cookie' by the trainer (supposedly meaning 'Please use your key to open that cabinet and get out a cookie for me to eat') may actually represent Koko's 'flailing around producing signs at random in a purely situation-bound bid to obtain food from her trainer, who was in control of a locked treat cabinet. ... Koko never said anything: never made a definite truth claim, or expressed a specific opinion, or asked a clearly identifiable question. Producing occasional context-related signs, almost always in response to Patterson's cues, after years of intensive reward-based training, is not language use.'

To summarize, it is still unclear whether animals other than humans can learn to use a language. Even though we may admit the possibility, their use of words is different from that of adult humans. At best, the animal's acquired linguistic capacity is not better than a three-year-old child.

LANGUAGE AREAS OF THE BRAIN

It seems clear that the complex and flexible system of language humans use is unique. Because of the lack of a legitimate animal model, studying details of the neural processes essential to language is limited. We have made enormous progress in understanding the neural processes underlying many brain functions that are shared by humans and other animals. For example, we can explain learning and memory in terms of altered neural circuit dynamics as a consequence of strengthened neural connections (enhanced synaptic efficacy; see chapter 4). Furthermore, we have identified molecular processes underlying synaptic efficacy change. Scientists can even manipulate specific neurons (artificially turn on and off specific neurons using a technique called optogenetics) to implant a false memory into a mouse. Compared to our understanding of the neural basis of memory, our understanding of the neural basis of language is far behind. Nevertheless, we have identified regions of the human brain that are specialized in language processing.

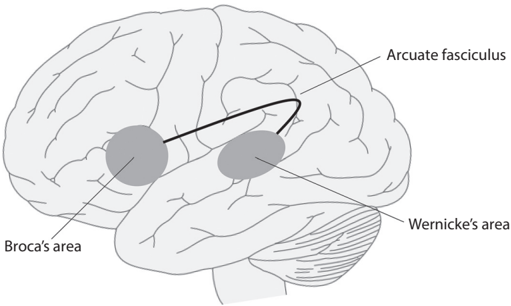

The first identified area specialized in language processing is Broca's area. In 1861, a French neurologist, Paul Broca, described a patient who lost the ability to speak without other physical or intellectual deficits. The patient's name was Louis Victor Leborgne, but he was known as Tan because 'tan' was the only syllable he could utter. A postmortem examination revealed a large lesion in the lower middle of the left frontal lobe (the left inferior frontal gyrus), the area now known as Broca's area (see fig. 12.1). People with damage in that area have relatively intact comprehension but have great difficulty speaking. Their speech is often telegraphic, consisting mostly of nouns and verbs. This type of aphasia is called Broca's, nonfluent, or motor aphasia.

A few years later, a German neurologist, Carl Wernicke, observed a different type of aphasia. These patients can speak fluently but have difficulty in comprehension. Even though their speech is fluent (rhythmic and grammatical), it does not make sense, and they are often unaware of it. It appears their speech production system operates without proper control over the contents. In these patients, damage is found in the posterior part of the left temporal lobe near the primary auditory cortex, the area now known as Wernicke's area (see fig. 12.1). This type of aphasia is called Wernicke's, fluent, or sensory aphasia.

FIGURE 12.1. Broca's and Wernicke's areas. In the Wernicke-Geschwind model, these areas oversee language production and comprehension, respectively, and they exchange information via the arcuate fasciculus, which is the major axon bundle connecting them. When we repeat spoken words, speech sounds, first processed by the auditory system, are converted into meaningful words in Wernicke's area. The word signals are then sent to Broca's area (via the arcuate fasciculus) where they are converted into motor signals to move muscles for speech production. When we read written text, visual signals, initially processed by the visual system, are transformed into pseudo-auditory signals and sent to Wernicke's area. Wernicke's area then converts those signals into meaningful words.

Wernicke proposed an early neurological model of language that was later extended by Norman Geschwind. Although the Wernicke-Geschwind model has been enormously influential, it is based on oversimplifications and is incorrect in many respects. For instance, there are no sharp functional distinctions between Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia; most aphasias involve both comprehension and speech deficits. Some argue that 'the model is incorrect along too many dimensions for new research to be considered mere updates.' Moreover, language processing involves multiple levels of processing (phonological, syntactic, and semantic) and interactions with multiple neural systems (such as motor, memory, and executive control systems). Hence, framing language processing merely as comprehension and production would not be useful in revealing diverse neural processes underlying language. More elaborate neurological models of language now focus on functional subcomponents of language processing rather than a comprehension versus production distinction. We are not going to examine these new models here, but the field is moving 'from coarse characterizations of language and largely correlational insights to fine-grained cognitive analyses aiming to identify explanatory mechanisms.'

LANGUAGE AND THOUGHT

The Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde once wrote, 'There is no mode of action, no form of emotion, that we do not share with the lower animals. It is only by language that we rise above them, or above each other—by language, which is the parent, and not the child, of thought.'

I began this chapter by emphasizing the role of language in sharing and accumulating knowledge across generations—the communication aspect of language. From this standpoint, language should be considered the child of thought—the means of expressing our inner thoughts. However, according to Wilde, language not only expresses but also shapes our thoughts, and this view has been shared by many renowned figures such as Ludwig Wittgenstein ('The limits of my language mean the limits of my world') and Bertrand Russell ('Language serves not only to express thoughts, but to make possible thoughts which could not exist without it').

No one would disagree that language influences thought. There is no doubt that 'language use has powerful and specific effects on thought. That's what it is for, or at least that is one of the things it is for—to transfer ideas from one mind to another mind.' Most of us hear an 'inner voice' or 'inner speech' while thinking. However, is language necessary for thought? If we lose language, do we lose thought as well? The answer to this question is clear: 'Not really.' Neuroscientific studies indicate that the brain areas linked to language are distinct from those linked to other cognitive functions such as memory, reasoning, planning, decision-making, and social cognition. Also, people with global aphasia, meaning they lost their linguistic capacity due to brain damage, can perform a variety of tasks requiring abstract reasoning. Furthermore, as we discussed in chapter 8, we are not the only animal species capable of abstract reasoning; chimpanzees and dolphins, for example, show impressive abstract inference capabilities. It is thus clear that language is not a prerequisite for thought. Many people come up with creative ideas through nonverbalized thinking. Albert Einstein claimed that imagining he was chasing a beam of light played a memorable role in developing the theory of special relativity. In fact, some people think without internal speech.

Although thinking without words is possible, it does not necessarily indicate that language has no role in shaping our thoughts. There has been much debate on whether and how language influences thought. Some argue that the primary role of language is limited to communication. Language enables the expression of inner thoughts but is not necessary for abstract thought itself. According to the influential language of thought hypothesis, we think using a mental language (often called 'mentalese') that has a linguistic structure. In other words, thoughts are really 'sentences in the head.' From this standpoint, it is unlikely that the influence of language on thought goes beyond that through its role in communication:

Language is a lot like vision. Language and vision are both excellent tools for the transfer of information. People who are blind find it harder to pick up certain aspects of human culture than people who can see, because they lack the same access to books, diagrams, maps, television, and so on. But this does not mean that vision makes you smart, or that explaining how vision evolves or develops is tantamount to explaining the evolution and development of abstract thought. Language may be useful in the same sense that vision is useful. It is a tool for the expression and storage of ideas. It is not a mechanism that gives rise to the capacity to generate and appreciate these ideas in the first place.

Contrary to this view, many people consider language as something more than a vehicle for the communication of thought. A strong version of this perspective, known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis or the linguistic relativity hypothesis, argues that our perception of the world is determined by the structure of a specific language we use. According to this hypothesis, Chinese and English speakers may have different ways of thinking. This hypothesis, at least in its radical version, is not widely accepted. However, many researchers believe that language can exert profound influences on our thoughts, especially those involving abstract concepts, beyond its role in communication.

For example, Guy Dove views language as a form of neuroenhancement, stating that 'the neurologically realized language system is an important subcomponent of a flexible, multimodal, and multilevel conceptual system. It is not merely a source for information about the world but also a computational add-on that extends our conceptual reach.' Anna Borghi emphasizes the role of language in representing abstract concepts: 'The potentialities of language are maximally exploited in representing abstract concepts: labels can help us to glue together the heterogeneous members of abstract concepts, and inner speech can improve the capability of our brain to track information on internal states and processes and to introspectively look at ourselves.'

According to this perspective, language is not merely used for exchanging ideas but also plays a role in representing abstract concepts such as liberty and integrity (but not much in representing concrete concepts such as table and cat). In this regard, Lupyan and Winter noted that language is way more abstract than iconic, even though iconicity—the resemblance of a word form to its meaning (tweet, click, and bang are examples of iconic words)—can be immensely useful in language learning and communication. According to them, 'abstractness pervades every corner of language' and 'the best source of knowledge about abstract meanings may be language itself.' We learn many abstract concepts by learning language rather than through actual interactions with the world.

People with aphasia show no impairment (or only weak impairment) in abstract reasoning. This argues against the claim that language should be considered a 'neuroenhancement' that extends our conceptual reach. However, language deprivation in childhood (deaf children born to hearing parents are often insufficiently exposed to sign language in their first few years of life) can lead to 'language deprivation syndrome,' which involves deficits in a variety of cognitive functions, such as understanding cause and effect and inferring others' intentions. Brain imaging studies revealed changes in cortical architecture and activation patterns in these children. Intriguingly, some observations point to a global deficit in their abstraction abilities. 'People with language deprivation do not excel at such seemingly nonverbal (but clearly conceptual) skills as playing chess or doing math... They can struggle to name basic feelings, to recognize the social boundaries that are encoded in words such as 'girlfriend,' or to reflect on their own experiences. They struggle to see patterns and make generalizations. Lessons learned in one arena are not easily applied to others.'

Thus, while available evidence is limited, language may play a role in expanding and refining abstract thinking during the critical period. Language may play a scaffolding role—'essential in the construction of a cognitive architecture, but once the system achieves a level of stability, the linguistic scaffolding can be removed.' Language may be one of the critical factors during development that pushes the boundary of thought deep into the abstract domain, allowing us to think seamlessly using both concrete and abstract concepts, which sometimes leads to a category mistake (see chapter 8). Again, the evidence is limited. What we speculated about the potential role of language in abstraction may or may not be correct. The jury is still out.

ORIGIN OF LANGUAGE

Even though uncertainty remains regarding the language-thought relationship, there is no doubt that the acquisition of linguistic capacity was a monumental step in human evolution. How have we acquired this capacity? What is the origin of language? This is a critical issue to understand how we have become what we are—Homo innovaticus. The origin of language has been debated for a long time among linguists, anthropologists, philosophers, psychologists, and neuroscientists. There are many perspectives, some of which are in conflict with one another. Unfortunately, that indicates that we are still far from fully understanding this matter.

Understanding the origin of language is a tough challenge for several reasons. First, language is unique to humans. No other animal communication system comes close to the complex, flexible, and powerful system humans use for communication. Consequently, unlike many other biological functions, it is difficult to gain insights from comparative approaches (i.e., examining and comparing language functions in diverse animal species). It is also difficult to perform invasive studies (such as recording neural activity with a microelectrode or inactivating a localized brain area) due to the lack of an animal model.

Second, we lack direct fossilized records of language. It is difficult to relate archaeological records directly to the evolution of language. Likewise, brain endocasts can tell us little about language function. Fossil records of speech organs, such as the vocal tract, could be related to the evolution of speech, but there is a huge gap between the capacity for producing articulated sounds and the capacity for grammatically combining symbols to generate novel expressions. The laryngeal descent theory has been popular for the past fifty years. This theory contends that laryngeal descent occurred in our ancestors, but not in other primates, around two hundred thousand years ago, allowing for the production of contrasting vowel sounds, the development of speech, and finally the development of language in Homo sapiens. However, a recent comprehensive review concludes that 'evidence now overwhelmingly refutes the longstanding laryngeal descent theory, which pushes back 'the dawn of speech' beyond ~200 ka ago to over ~20 Ma ago.'

Third, the dynamics of social interaction must be considered in explaining the evolution of language. It is often less straightforward to explain the evolution of a social trait, such as altruism, compared to a nonsocial trait. Perhaps humans are the only animals showing true altruism. We often help strangers without expecting reciprocal benevolence. We even take personal loss to punish norm violators (altruistic punishment). These human behaviors are not readily explained in terms of biological fitness (the ability to pass on our own genes to the next generation). Obviously, altruism enhances the survival fitness of a group. However, within a group, the survival fitness would be higher among selfish individuals. Hence, it is not clear how altruistic traits were selected over selfish ones across generations. Likewise, being able to share information would be a big advantage for a group. However, it is unclear how this trait initially appeared and survived across generations. Language is useless if you are the only one who can speak.

Here, instead of a comprehensive overview of theories on the origin of language, we will selectively examine a few only to the extent to reveal the diversity of voices in the field. One of the debates related to the origin of language is whether language evolved suddenly or gradually. Recall the debate over the evolution of behavioral modernity and the human revolution (see chapter 10). Noam Chomsky proposed that modern language evolved suddenly as a consequence of a fortuitous chance mutation.

Human capacities for creative imagination, language and symbolism generally, mathematics, interpretation and recording of natural phenomena, intricate social practices, and the like, a complex of capacities that seem to have crystallized fairly recently, perhaps a little over 50,000 years ago, among a small breeding group of which we are all descendants—a complex that sets humans apart rather sharply from other animals, including other hominids, judging by traces they have left in the archaeological record. ... The invention of language ... was the 'sudden and emergent' event that was the 'releasing stimulus' for the appearance of the human capacity in the evolutionary record—the 'great leap forward' as Jared Diamond called it, the results of some genetic event that rewired the brain, allowing for the origin of modern language with the rich syntax that provides a multitude of modes of expression of thought, a prerequisite for social development and sharp changes of behavior that are revealed in the archaeological record.

The discovery of the gene FOXP2 raised the hope that we might be able to identify the 'fortuitous mutation' Chomsky proposed. FOXP2 was identified by the 2001 genetic analysis of a British family known as KE; half of its members were severely impaired in speech production. Many of the affected KE family members have low IQs, but some of them show language problems with normal IQs, indicating that the language problem is not because of a general cognitive impairment. A subsequent comparative genetic study has shown that the human FOXP2 protein differs from those of other great apes only by two amino acids. This study also found evidence for 'selective sweep,' a process in which a rare beneficial mutation rapidly increases in frequency by natural selection. These findings suggest that a beneficial mutation in the FOXP2 gene, estimated to have happened about two hundred thousand years ago, may have triggered the development of modern language in humans. However, contrary to the initial report, a later study found no evidence for a selective sweep in FOXP2. Moreover, an ancient DNA sequencing study revealed that Neanderthals share the evolutionary changes in FOXP2 (two amino acids that differ from other great apes) with modern humans. Thus, the beneficial changes in FOXP2 must have happened before the split of our ancestors from Neanderthals (about half a million years ago), but there is no clear evidence for language use by Neanderthals. Some advocate language use by Neanderthals, but many are skeptical about this possibility.

Currently, most researchers seem to favor the idea that human language evolved in steps over a long period, just like most biological functions did, even though it is unclear how exactly this gradual process unfolded during human evolution. The following is one hypothetical scenario for the steps of language evolution:

In an early stage, sounds would have been used to name a wide range of objects and actions in the environment, and individuals would be able to invent new vocabulary items to talk about new things. In order to achieve a large vocabulary, an important advance would have been the ability to 'digitize' signals into sequences of discrete speech sounds—consonants and vowels—rather than unstructured calls. This would require changes in the way the brain controls the vocal tract and possibly in the way the brain interprets auditory signals. ... A next plausible step would be the ability to string together several such 'words' to create a message built out of the meanings of its parts. This is still not as complex as modern language. It could have a rudimentary 'me Tarzan, you Jane' character and still be a lot better than single-word utterances. In fact, we do find such 'protolanguage' in two-year-old children, in the beginning efforts of adults learning a foreign language, and in so-called 'pidgins,' the systems cobbled together by adult speakers of disparate languages when they need to communicate with each other for trade or other sorts of cooperation. ... A final change or series of changes would add to 'protolanguage' a richer structure, encompassing such grammatical devices as plural markers, tense markers, relative clauses, and complement clauses ('Joe thinks that the earth is flat').

Another passionately debated issue regarding the origin of language is the relationship of language to other cognitive functions. Some argue that the human language system is a stand-alone system separated from all other mental faculties, while others argue that language draws on other cognitive functions. Again, let's examine a few of these theories.

Michael Tomasello is one of the researchers advocating the idea that language is a manifestation of more general cognitive functions. He argues that humans and great apes both have the ability to comprehend the intentions of others. However, only humans engage in activities involving joint intentions and attention, which he named 'shared intentionality': 'In addition to understanding others as intentional, rational agents, humans also possess some kind of more specifically social capacity that gives them the motivation and cognitive skills to feel, experience, and act together with others—what we may call, focusing on its ontogenetic endpoint, shared (or 'we') intentionality. As the key social-cognitive skill for cultural creation and cognition, shared intentionality is of special importance in explaining the uniquely powerful cognitive skills of Homo sapiens.'

According to Tomasello, only humans have the cognitive capacity to represent a shared goal (e.g., you and I work together to open a box) and joint intention (e.g., you hold the box while I cut it open). The capacity to represent shared intentionality begins to emerge around the first birthday when children start using words. He argues that unique human cognitive capacities, such as language use and theory of mind, are derived from the understanding and sharing of intentions (joint intentionality).

Saying that only humans have language is like saying that only humans build skyscrapers, when the fact is that only humans (among primates) build freestanding shelters at all. Language is not basic; it is derived. It rests on the same underlying cognitive and social skills that lead infants to point to things and show things to other people declaratively and informatively, in a way that other primates do not do, and that lead them to engage in collaborative and joint attentional activities with others of a kind that are also unique among primates.

Steven Pinker is among the researchers advocating the opposite view, namely that language is fundamentally different from other types of cognition. He argues that language evolved for the communication of complex propositions.

What is the machinery of language trying to accomplish? The system appears to have been put together to encode propositional information—who did what to whom, what is true of what, when, where and why—into a signal that can be conveyed from one person to another. It is not hard to see why it might have been adaptive for a species with the rest of our characteristics to evolve such an ability. The structures of grammar are well suited to conveying information about technology, such as which two things can be put together to produce a third thing; about the local environment, such as where things are; about the social environment, such as who did what to whom, when, where and why; and about one's own intentions, such as If you do this, I will do that, which accurately conveys the promises and threats that undergird relations of exchange and dominance.

Pinker contends that humans, unlike other animals, evolved to perform cause-and-effect reasoning and rely on information for survival. It would then be advantageous for them to come up with a means to exchange information. He argues that 'three key features of the distinctively human lifestyle—knowhow, sociality, and language—co-evolved, each constituting a selection pressure for the others.'

According to Marc Hauser, Noam Chomsky, and Tecumseh Fitch, a distinction should be made between the faculty of language in the broad sense (FLB) and in the narrow sense (FLN). The FLN includes only the core computational mechanisms of recursion (a clause can contain another clause so that one can generate an infinite number of sentences of any size, such as 'I wonder if he knows that she believes that we suspect him as the criminal') and the FLB has two additional components—a sensory-motor system and a conceptual-intentional system. Together with the FLN, they provide 'the capacity to generate an infinite range of expressions from a finite set of elements' (discrete infinity).

They hypothesize that the FLN is recently evolved, unique to humans, and unique to language, so 'there should be no homologs or analogs in other animals and no comparable processes in other domains of human thought.' By contrast, many aspects of the FLB are shared with other vertebrates. They also speculate that the FLN (recursion mechanism) may have evolved 'to solve other computational problems such as navigation, number quantification, or social relationships.'

One possibility, consistent with current thinking in the cognitive sciences, is that recursion in animals represents a modular system designed for a particular function (e.g., navigation) and impenetrable with respect to other systems. During evolution, the modular and highly domain-specific system of recursion may have become penetrable and domain-general. This opened the way for humans, perhaps uniquely, to apply the power of recursion to other problems. This change from domain-specific to domain-general may have been guided by particular selective pressures, unique to our evolutionary past, or as a consequence (by-product) of other kinds of neural reorganization.

I mentioned the social nature of language as a challenge to understanding its origin. One of the theories we examined, Tomasello's shared intentionality theory (sharing goals and intentions with others), deals with this issue, but it's not the only one. Numerous other theories focus on the social nature of language. To examine one more, the ritual/speech coevolution theory argues that we must consider the whole human symbolic culture to understand the origin of language. Advocates of this theory propose that language works only after establishing high levels of trust in society because words are cheap (low-cost) signals and therefore inherently unreliable. Chris Knight suggests that 'any increase in the proportion of trusting listeners increases the rewards to a liar, increasing the frequency of lying. Yet until hearers can safely assume honesty, their stance will be indifference to volitional signals. Then, even lying will be a waste of time. In other words, there is a threshold of honest use of conventional signals, below which any strategy based on such signaling remains unstable. To achieve stability, the honest strategy has to predominate decisively over deception.' Therefore, in order for verbal communication to be possible, 'what is at stake is not only the truthfulness of reliability of particular messages but credibility, credence and trust themselves, and thus the grounds of the trustworthiness requisite to systems of communication and community generally.'

Knight further describes how this theory highlights the role of religion and ritual in establishing social trust: 'Words are cheap and unreliable. Costly, repetitive and invariant religious ritual is the antidote. At the apex is an 'ultimate sacred postulate'—an article of faith beyond possible denial. Words may lie, so it is claimed, but 'the Word' emanates from a higher source. Without such public confidence upheld by ritual action, faith in the entire system of interconnected symbols would collapse. During the evolution of humanity, the crucial step was therefore the establishment of rituals capable of upholding the levels of trust necessary for linguistic communication to work.'

Thus, to understand the origin of language, we must consider a wider context—the human symbolic culture as a whole—of which language is one integral component, according to this theory.

MIRROR NEURON HYPOTHESIS

As can be seen from these examples, there exist widely divergent views on the origin of language that span multiple disciplines. Before wrapping up this chapter, let's examine one more theory that was derived from neuroscientific research: the mirror neuron hypothesis.

What are mirror neurons? They are neurons found in the monkey premotor cortex that are activated by both performing and observing an action. The premotor cortex is located between the prefrontal cortex and primary motor cortex. The prefrontal cortex plans a goal-directed behavior (discussed in chapter 9) and the primary motor cortex controls individual muscle contractions. The premotor cortex is thought to play an in-between role of selecting an appropriate motor plan to achieve a desired outcome (e.g., grasping an object). Roughly speaking, the prefrontal, premotor, and primary motor cortices are in charge of strategies, tactics, and execution, respectively, of goal-directed behavior.

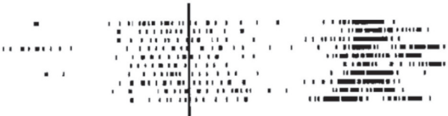

In the 1990s, Giacomo Rizzolatti and colleagues discovered that some neurons in the monkey premotor cortex fire when the monkey is performing a certain action (such as grasping an object) as well as observing the same action performed by another (see fig. 12.2). A later study showed that not only visual (seeing) but also auditory (hearing) signals are effective in activating some mirror neurons (audiovisual mirror neurons) in the monkey premotor cortex. For example, a neuron in the premotor cortex fired when the monkey broke a peanut (doing), when the monkey observed a human breaking a peanut (seeing), and when the monkey heard the peanut being broken without seeing the action (hearing). This area of the premotor cortex in the monkey brain (area F5) is thought to be homologous to Broca's area in the human brain, and Broca's area also increases activity during both performing and observing a finger movement.

FIGURE 12.2. A mirror neuron recorded from the monkey premotor cortex. This neuron elevated its activity in response to the observation of the experimenter's grasping action as well as the monkey's own grasping action. Figure reproduced from Antonino Errante and Leonardo Fogassi, 'Functional lateralization of the mirror neuron system in monkey and humans,' Symmetry 13, no. 1 (2021): 77 (CC BY).

These observations led to the proposal that the mirror neuron system (or 'observation/action matching' system) may have served as the basis for the evolution of language.

Mirror neurons in monkey premotor cortex provide the primate motor system with an intrinsic capacity to compare the actions it generates with those generated by other individuals. It has therefore the potential to be both the sender and the receiver of message. ... The problem of transforming an underlying case structure to a sentence (one of many possibilities) which expresses it may be seen as analogous to the nonlinguistic problem of planning the right order of actions to achieve a complex goal. Suppose the monkey wants to grab food, but then—secondarily—realizes it must open a door to get the food. Then in planning the action, the order food-then-door must be reversed. This is like the syntactic problem of producing a well-formed sentence, but now viewed as going from 'ideas in the head' to a sequence of words/actions in the right order to achieve some communicative or instrumental goal.

This theory is in line with the view that the origin of language is gestural communication rather than animal calls. Note that the mirror neuron system alone is insufficient to support the syntax of human language, especially hierarchical recursion. According to Michael Arbib and Mihail Bota, linking Broca's area to the prefrontal cortex planning system allows us to 'assemble verb-argument and more complex hierarchical structures, finding the words and binding them correctly.'

In summary, there is no doubt that language is a critical element of human innovation. The acquisition of linguistic capacity was a truly monumental step in human evolution. Language allows the exchange of ideas and the accumulation of knowledge across generations. Language may also play a role in setting up proper abstract-thinking capacity during development. Undoubtedly, understanding the origin of language is critical for understanding how we have become Homo innovaticus. Unfortunately, the origin of language is far from being clear, partly due to the uniqueness of human language. No other animal communication comes close to human language in terms of flexibility, complexity, and power. Its uniqueness, together with the paucity of archaeological evidence and its social nature, poses challenges to studying the origin of language. We have many theories but are yet to draw a robust consensus on how the faculty of language has evolved; 'The richness of ideas is accompanied by a poverty of evidence.' Nevertheless, the origin of language draws interest from multiple disciplines. Many scholars have attempted to solve this problem by standing on the shoulders of previous great thinkers, which is made possible because of language.