Chapter Ten

THE HUMAN REVOLUTION AND ASSOCIATED BRAIN CHANGES

HUMAN REVOLUTION

Looking back at the past may help us guess what critical changes in the brain enabled high-level abstract thinking in Homo sapiens. Specifically, comparing fossilized skulls and archaeological evidence may provide a clue on the neural basis of high-level abstraction. In this regard, archaeological studies have identified a suite of innovations that characterize modern human behavior, such as verbal communication, exchange of goods, sophisticated burials, artistic expression, and organized societies, in Eurasia during the Upper Paleolithic, about forty to fifty thousand years ago. This was once known as the 'human revolution' because of a relatively sudden appearance of a package of modern human behavior, even though archeologists have found earlier sporadic evidence for some of these characteristics.

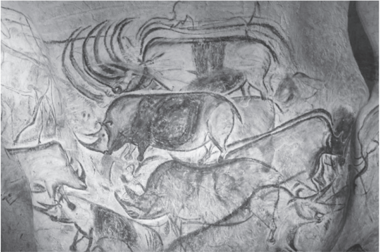

These archaeological findings strongly suggest that our Eurasian Upper Paleolithic ancestors had a cognitive capacity not inferior to that of modern humans. Figure 10.1 shows some of the Upper Paleolithic paintings discovered in Europe. Many tools, sculptures, and wall paintings from this era are artistically excellent even by today's standards. Symbolic and abstract thinking are among the core cognitive functions associated with art.

Figure 10.1: Upper Paleolithic paintings (replicas): Altamira (upper left), Lascaux (upper right), and Chauvet Cave (lower)

Figure 10.1: Upper Paleolithic paintings (replicas): Altamira (upper left), Lascaux (upper right), and Chauvet Cave (lower)

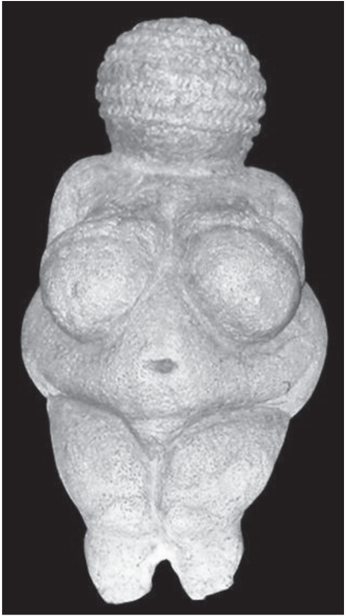

For example, the Venus figurine (see fig. 10.2), commonly found in Upper Paleolithic sites throughout Eurasia, is thought to symbolize fertility.

Figure 10.2: Venus of Willendorf

Figure 10.2: Venus of Willendorf

One popular theme of art throughout the history of mankind is sex and fertility, i.e., the preservation of our species. The Venus figurine may be an ancient version of present-day African fertility dolls, which symbolize a fertility goddess. In general, an artist needs the cognitive capacity to project their symbolic content onto a mental image while alternating between their own and potential viewers' perspectives in order to communicate ideas, feelings, and experiences. The Upper Paleolithic art hints at our ancestors' superb symbolic and abstract-thinking abilities.

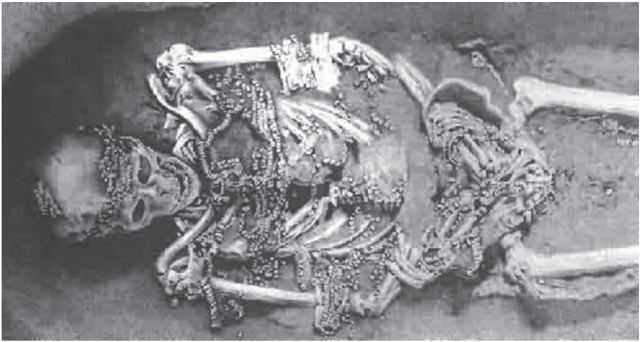

Ornament burial is another line of evidence for the behavioral modernity of our Upper Paleolithic ancestors. Graves are regarded as clear evidence of religious beliefs, a hallmark of modern human behavior. Figure 10.3 depicts a sophisticated ornamental burial from that period.

Figure 10.3: An Upper Paleolithic burial found at Sungir, Russia Even though the view that burials became ubiquitous and elaborate only during the Upper Paleolithic appears to be an oversimplification, sophisticated and elaborate burials such as the one shown suggest that our Upper Paleolithic ancestors thought about what happens after death and believed in the transmigration of the soul as many modern humans do. Homo sapiens' spiritual awareness and religiousness may not have changed much since then.

Figure 10.3: An Upper Paleolithic burial found at Sungir, Russia Even though the view that burials became ubiquitous and elaborate only during the Upper Paleolithic appears to be an oversimplification, sophisticated and elaborate burials such as the one shown suggest that our Upper Paleolithic ancestors thought about what happens after death and believed in the transmigration of the soul as many modern humans do. Homo sapiens' spiritual awareness and religiousness may not have changed much since then.

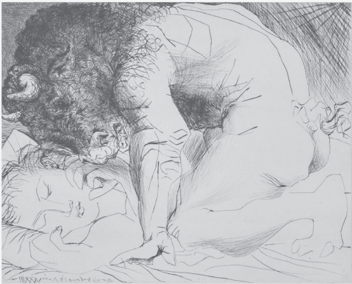

The archeological phenomena in the Upper Paleolithic indicate that our ancestors had well-developed cognitive capacity, including high-level symbolic thinking. If an infant of that period was teleported to the present day, he or she could grow up to be a scientist, artist, writer, or politician, just like any other modern infant. Compare the two drawings in Figure 10.4.

Figure 10.4: The beast within. (Left) Charcoal drawing found in Chauvet Cave, France. (Right) Pablo Picasso's Minotaur carressant une dormeuse The left is a charcoal drawing found in the Chauvet Cave, France, which is estimated to be about thirty thousand years old. A bison-headed man is looming over a woman's naked body that has an emphasized pubic triangle. The right is a drawing by Pablo Picasso, Minotaur carressant une dormeuse. The resemblance is striking. It appears that both represent a fantasy embedded deep in the male psyche ('the beast within'). The Chauvet Cave was not discovered until after Picasso's death. Thus, Picasso created the piece without being aware of that similar drawing. However, he visited the Lascaux caves in southwestern France and saw wall paintings like the ones shown in figure 10.1. Picasso, impressed by them, reportedly said to his guide, 'They've invented everything.'

Figure 10.4: The beast within. (Left) Charcoal drawing found in Chauvet Cave, France. (Right) Pablo Picasso's Minotaur carressant une dormeuse The left is a charcoal drawing found in the Chauvet Cave, France, which is estimated to be about thirty thousand years old. A bison-headed man is looming over a woman's naked body that has an emphasized pubic triangle. The right is a drawing by Pablo Picasso, Minotaur carressant une dormeuse. The resemblance is striking. It appears that both represent a fantasy embedded deep in the male psyche ('the beast within'). The Chauvet Cave was not discovered until after Picasso's death. Thus, Picasso created the piece without being aware of that similar drawing. However, he visited the Lascaux caves in southwestern France and saw wall paintings like the ones shown in figure 10.1. Picasso, impressed by them, reportedly said to his guide, 'They've invented everything.'

ANATOMICALLY MODERN HUMANS

It was generally believed until the late 1980s that modern Homo sapiens appeared forty to fifty thousand years ago in Eurasia (European model). This is when the Cro-Magnons appeared and Neanderthals disappeared. Cro-Magnons were tall and their brains were about 30 percent larger than those of modern humans. The skulls of Cro-Magnons and modern humans are round-shaped, while those of Neanderthals are much more elongated from front to back (see fig. 10.5).

Figure 10.5: Differences in Neanderthal and modern human skulls It is unclear why our ancestors survived while Neanderthals did not, but one possibility is that Cro-Magnons had a cognitive advantage. Because their foreheads were flatter, and because the prefrontal cortex is a critical brain area for many highly cognitive functions, as discussed in chapter 9, it was natural to suspect that Cro-Magnons had advanced cognitive capacity due to their well-developed prefrontal cortex. According to this viewpoint, the human revolution coincides with the expansion of the prefrontal cortex.

Figure 10.5: Differences in Neanderthal and modern human skulls It is unclear why our ancestors survived while Neanderthals did not, but one possibility is that Cro-Magnons had a cognitive advantage. Because their foreheads were flatter, and because the prefrontal cortex is a critical brain area for many highly cognitive functions, as discussed in chapter 9, it was natural to suspect that Cro-Magnons had advanced cognitive capacity due to their well-developed prefrontal cortex. According to this viewpoint, the human revolution coincides with the expansion of the prefrontal cortex.

Subsequent discoveries indicate, however, that the story is not that simple. For example, the fossil records of anatomically modern Homo sapiens found in the Qafzeh and Skhul caves in Israel were initially thought to be about 40,000 years old according to the European model. However, a more precise estimation based on heat-induced emission of light (this method is called thermoluminescence dating: energized electrons accumulate over time in proportion to the radiation a specimen received from the environment) in the late 1980s indicated that the fossil records are about 100,000 years old. Subsequent findings of new fossil records pushed back the origin of anatomically modern humans earlier and earlier. Archeological findings indicate that anatomically modern Homo sapiens appeared at least 200,000 years ago, and the fossil records for more primitive Homo sapiens found in Africa date back to about 300,000 years ago. DNA studies also support the idea that anatomically modern humans appeared in Africa much earlier than the Upper Paleolithic. It is now well agreed that anatomically modern Homo sapiens appeared in Africa long before the Upper Paleolithic and spread throughout Eurasia over thousands of years, replacing other early humans such as Neanderthals (the 'Out-of-Africa' model).

ORIGIN OF BEHAVIORAL MODERNITY

Thus, there appears to be a time lag between the appearance of anatomically modern humans and modern human behavior. What then was the main driving force for its sudden appearance? Some scholars advocate a neurological change. A fortuitous mutation may have induced a subtle but critical neurological change to promote cognitive capability without a major change in the shape of the skull. Alternatively, environmental and social factors, such as environmental stress and increased population density, rather than a biological change, might be the main driving force.

Some researchers deny the concept of a human revolution, arguing that characteristics of modern human behavior appeared over a long period. They contend that technological and cultural innovations appeared and disappeared multiple times in the history of Homo sapiens due to factors such as population loss and environmental instability. This, along with the loss of archaeological records, may explain why there is only patchy evidence for behavioral modernity before the Upper Paleolithic. It would be difficult to reconstruct events that occurred tens of thousands of years ago. We must wait until archaeologists and paleoanthropologists present compelling evidence supporting a particular hypothesis. Nonetheless, it appears that our ancestors acquired the capacity for high-level abstraction at least by the Upper Paleolithic.

PALEONEUROLOGY

Paleoneurology is the study of brain evolution by the analysis of the endocast, which is the internal cast of the skull. It would be difficult to detect a subtle neurological change during evolution by examining the endocast. However, major changes in brain structure are likely to occur alongside corresponding changes to it. Hence, if Homo sapiens' cognitive capacity has reached the level of modern humans as a result of major structural changes in the brain, paleoneurological research may be able to provide valuable insights into them. In this regard, studies in paleoneurology have identified changes in the size and shape of the braincase during human evolution.

Let's look at a recent study published in 2018. Three scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany—Simon Neubauer, Jean-Jacques Hublin, and Philipp Gunz—carefully analyzed twenty Homo sapiens fossils belonging to three different periods (300,000-200,000, 130,000-100,000, and 100,000-35,000 years ago). They found that the brain shape of only the third group, the most recent fossils, matches that of present-day humans. This indicates that Homo sapiens' brain shape reached the modern form between 100,000 and 35,000 years ago. Because this period corresponds to the emergence of modern human behavior in the archaeological record, it is possible that these neurological changes played a significant role in the development of modern human behavior.

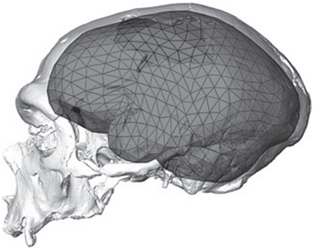

How exactly does the brain shape of the third group differ from the other two? The size of the brain was similar across all three groups, but the shape of the brain became more globular (see fig. 10.6).

Figure 10.6: Brain globalization during evolution Further analysis indicated bulging of two brain regions, the parietal cortex and cerebellum (see fig. 10.7), during the brain globalization process.

Figure 10.6: Brain globalization during evolution Further analysis indicated bulging of two brain regions, the parietal cortex and cerebellum (see fig. 10.7), during the brain globalization process.

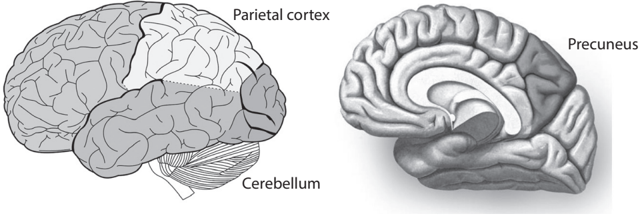

Figure 10.7: Parietal cortex, cerebellum, and precuneus Here we will focus on the parietal cortex because neocortical expansion is likely to be responsible for advanced cognitive capability in humans (see chapter 8), even though we cannot reject the possibility that changes in the cerebellum contributed greatly to the appearance of modern human behavior.

Figure 10.7: Parietal cortex, cerebellum, and precuneus Here we will focus on the parietal cortex because neocortical expansion is likely to be responsible for advanced cognitive capability in humans (see chapter 8), even though we cannot reject the possibility that changes in the cerebellum contributed greatly to the appearance of modern human behavior.

Note that it is difficult to get a clear picture of the shape of the brain from the shape of the braincase. Moreover, the parietal cortex is a wide area. Nevertheless, studies have shown that a particular region of the parietal cortex, namely the precuneus (see fig. 10.7), is proportionally much larger in humans than in chimpanzees; its size is also correlated with the parietal bulging in modern humans. Based on these findings, Emiliano Bruner at Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (National Center for Research on Human Evolution) in Spain proposed that precuneus expansion may be associated with recent human cognitive specialization.

PRECUNEUS

Unfortunately, we know relatively little about the precuneus. It is rare to find a human patient with selective damage to the precuneus (such as by stroke), and there are very few studies on this enigmatic brain region. Andrea Cavanna and Michael Trimble, in a paper published in 2006, reviewed published human brain imaging studies and grouped four different mental processes the precuneus appears to be involved in: visuospatial imagery (spatially guided behavior), episodic memory retrieval (remembering autobiographical memory), self-processing (representation of the self in relationship with the outside world), and consciousness. Thus, the precuneus is activated in association with a diverse array of cognitive processes, which is not surprising given that it is an association cortex far removed from primary sensory and motor areas and extensively connected with higher association cortical areas.

Subsequent studies additionally found the involvement of the precuneus in artistic performance and creativity. For example, the gray matter density of the precuneus is higher in artistic students than in non-artistic students, and the functional connectivity (the correlation in activity over time between two brain regions, which is an index of how closely two brain areas work together) between the precuneus and thalamus is stronger in musicians than in nonmusicians. Also, the activity of the precuneus is correlated with verbal creativity and ideational originality. These findings suggest that the expansion of the precuneus may have been a significant stage in the evolution of the human capacity to form high-level abstract concepts.

As an alternative possibility, the human precuneus may facilitate the use, rather than the formation, of high-level abstract concepts. The precuneus is a 'hot spot' of the default mode network. It consumes more energy (glucose) than any other cortical area during conscious rest. As we examined in chapter 1, the default mode network is activated when we engage in internal mentation (conceptual processing) and deactivated when we pay attention to external stimuli (perceptual processing). Also notable is that the precuneus is activated across multiple behavioral states. According to brain imaging studies, the human brain consists of multiple, overlapping, and interacting neural networks that appear to serve distinct functions. One of them is the default mode network. Other well-characterized task-associated networks include the central executive network (or frontoparietal network; its major components are the dorsolateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices) and the salience network (its major components are the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and frontoinsular cortex). The precuneus is not only a core component of the default mode network but is also activated in several task-associated networks. The unusually high activity and metabolic rate of the human precuneus as well as its involvement across multiple brain networks suggest that it may play a pivotal role in integrating information from various brain networks, allowing the free use of high-level abstract concepts.

In summary, it is remarkable that a relatively sudden appearance of modern human behavior, the human revolution, coincides with the period when our ancestors' brain shape became globular. This observation suggests that the expansion of particular brain regions such as the precuneus may have contributed to the development of the human capability to form and utilize high-level abstract concepts.